Michael Nyman is not a pop star. Yet his best-selling soundtrack to Jane Campion’s The Piano has landed him in the commercial marketplace, writes GARY STEEL

He’s got a daunting schedule of promotional obligations, phone interviews coming out his ears, another tedious photoshoot in half an hour, and here he is, sitting in The Ritz, in Paris, talking to idiotic strangers who heard him for the first time on last year’s atypical soundtrack for Jane Campion’s The Piano.

He’s got a daunting schedule of promotional obligations, phone interviews coming out his ears, another tedious photoshoot in half an hour, and here he is, sitting in The Ritz, in Paris, talking to idiotic strangers who heard him for the first time on last year’s atypical soundtrack for Jane Campion’s The Piano.

The evocative, lushly romantic score has sold over 1.5 million copies, still hovers around the Billboard crossover charts, and was a Number 1 hit in Spain. Which means that Michael Nyman is suddenly the most popular composer alive. Having for many years carved out a specific niche in modern music with few rewards in terms of critical acclaim, popularity and riches, Nyman must surely find all the current hoopla quite insane. And – from the droll tone of his voice – it seems that the strain to come up with a follow-up to The Piano has weighed rather heavily.

The solution is an album that is neither a soundtrack, nor another full-scale project, but a sampling of his compositions over the past 15 years, Michael Nyman Live.

“Michael Nyman Live is a way to see how much of a real market for my music has been opened up by The Piano, and how much it only has to do with The Piano and the particular quality of the film, and the particular quality of the music,” says Nyman. “I’m very curious because now there’s a vast audience out there for my music. But maybe they don’t know it, because they don’t know who the composer of The Piano is… they may be of no curiosity to discover what else I’ve written.”

The live album also deftly dips right back to the beginning of Nyman’s recorded career by including two pieces from his long-deleted 1979 debut.

“It’s been a long process,” says Nyman, “and the album represents that process. My first concert as a mature composer in 1977 led off with ‘In Re Don Giovanni’, which is the opening track on the album. Now to me, that is a very smart, street-wise, perky piece of music which you would imagine would have created a lot of attention, but in 1977 no-one was interested.”

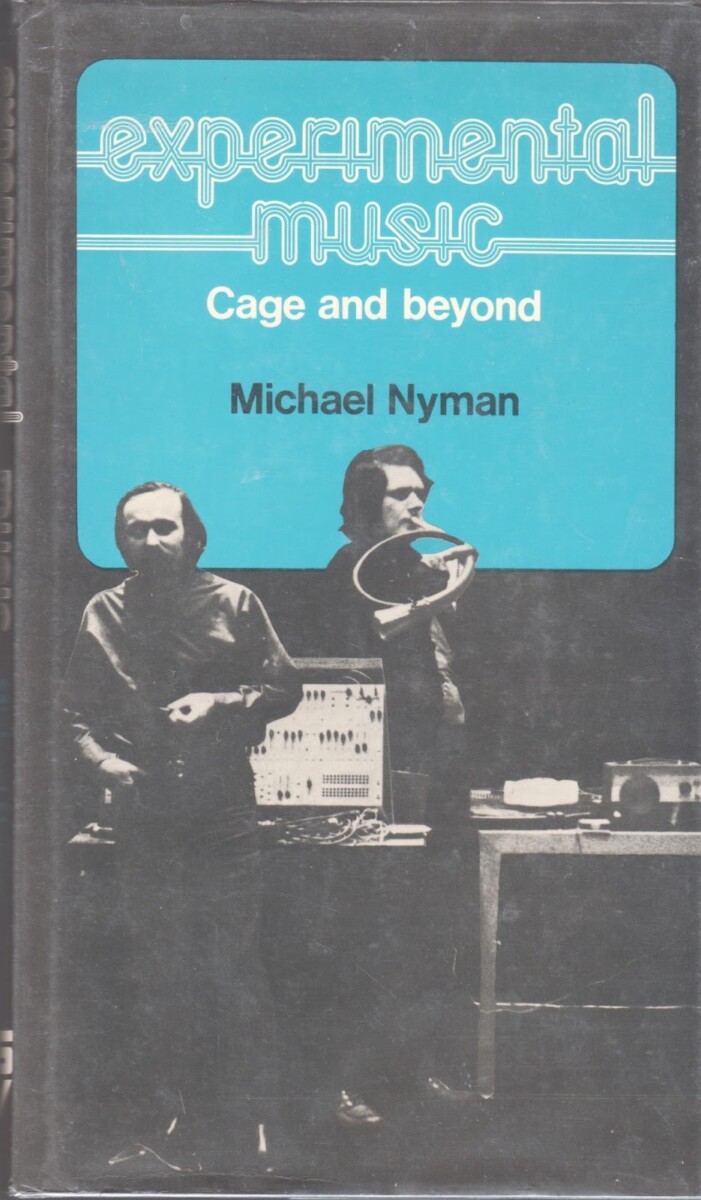

Nyman goes back much further than 1977, however. He was already composing by the mid-1960s, but that activity was sidelined by his studies in musicology, the avant-garde, and a career in music criticism. By the early ‘70s he was teaching, and wrote the definitive account of experimental music, Cage And Beyond, stopping on his way to coin the word ‘minimalism’.

He was instrumental – along with other teachers/composers like Gavin Bryars – in the crossover of ideas that occurred in the ‘70s when students of his like Brian Eno and David Cunningham (remember the deconstructivist pop group Flying Lizards?) took the ideas of John Cage and other experimentalists to the pop stage.

He was instrumental – along with other teachers/composers like Gavin Bryars – in the crossover of ideas that occurred in the ‘70s when students of his like Brian Eno and David Cunningham (remember the deconstructivist pop group Flying Lizards?) took the ideas of John Cage and other experimentalists to the pop stage.

“It was a particular kind of cross-fertilization that happened in England that I don’t think happened anywhere else. In fine art school, you would go in as a painter and come out as a composer. We were composers in the experimental tradition who taught in art school, and the influence of Cage was very strong. Brian Eno and David Cunningham and others were able to move over into our neck of the woods, and to use the power and influence that they had as rock musicians to produce and finance and generate projects that if we put through any record company wouldn’t have got any funding.

“Eno’s whole Obscure series came out of his interest in our work, and David Cunningham made a lot of money with ‘Money’, and he chose to finance my first album.”

Cunningham produced most of Nyman’s albums through the ‘80s, including the Peter Greenaway soundtracks that established Nyman’s reputation with a wider, but still woefully select audience.

“There was a much more open attitude amongst classical composers to what was going on in the rock world then, partly because the rock world was very interesting. But I think the last 10 years have been absolutely dire. I don’t think there’s been anything that anybody could or should have shown any interest in since punk,” he states, decisively.

Nyman’s decade-long collaboration with Peter Greenaway almost irretrievably connected the two, but at least provided Nyman with a platform for music that didn’t involve many of the normal concessions to film soundtrack work. With Greenaway, Nyman was often able to contribute completed works, utilizing his distinctive influences, from baroque to minimalism to the avant-garde.

“Most films deal with the same emotions, loss and love and sadness and lust, and I could imagine getting fed up with having to find musical equivalents of those situations,” says Nyman. “The brilliant thing about working with Greenaway was that all those things were not major concerns to him. So I would stroke my wings creatively and come up with music that was the most unexpected kind of music for the particular situation.”

Which is why Nyman hasn’t jumped at any Hollywood projects since the success of The Piano. “Hollywood has so many conflicting voices, so many people want to be heard. It’s a whole organizational thing, which would take me away from what I should be doing which is writing, recording, touring, even having a good time! To become a machine to churn out the right emotions doesn’t interest me at all, it’s kind of limited really.”

And even though the Greenaway projects gave Nyman a way to present his music without compromise, it also created a prison.

“People hated the Greenaway films, and therefore hated anyone associated with them, and would not have employed me to write a film score simply because of my connection with them. The association was that this was Greenaway music, when it was Nyman music and I would have written it anyway, whether I’d written if for the films or not.”

The way out of that prison was The Piano, but that’s opened the door to film soundtrack offers that don’t interest him. What does interest him is to find out if there is an audience for his operas, and numerous other projects.

“It’s very gratifying for me that a million-and-a-half people bought The Piano soundtrack album, and I’m very happy for that kind of music to be listened to in its own right by those kinds of numbers, but it would also be nice to see that as a way of entering into the rest of my work. The soundtrack… has to compete for attention, you deal with clean, clear, sometimes quite straightforward primary structures. There’s no point in wasting great erudite stuff on a film score which has to compete with sound effects and dialogue and may actually not be used in the film. Whereas if you write a string quartet you expect people to be able to sit down and listen to it in a concert hall, and give it all their concentration.”

Nyman is most proud of his operas, which include an adaptation of the Oliver Sachs book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat.

“Opera is the composer’s equivalent of a film,” says Nyman. “It’s a dramatic extension of what the composer does with the rest of his or her work. The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat was my idea. I wrote a review of Sachs’ book, I thought the title story would make a great opera. It was my own work, something I really wanted to do on a subject that was very close to me, where I could have as much control as possible over the project as a whole.”

It’s a source of grievance to Nyman that his most personal projects are the least known or heard, but there’s hope the live album might arouse curiosity. Unlike many other modern composers, Nyman’s work is openly influenced by several opposing schools of thought: the academic theories of the serialists, the simplicity of the minimalists and the structural integrity of the ‘great masters’. With Nyman, there are layers of clever experimental theory behind the compositions, but these seldom interfere with the music’s accessibility.

Nyman isn’t planning any rewrites of The Piano, despite pressure from the filmmakers to do so. Works in progress include the soundtrack for a Christopher Hampton film, Carrington (“It’s my first Emma Thompson film, I can die a happy man, he said with irony”), the soundtrack for an animated Japanese film version of The Diary Of Anne Frank (“Something I just couldn’t resist!”) and he’s working on his harpsichord concerto, the fourth string quartet, a trombone concerto, and an orchestral arrangement of Prospero’s Books. If that is, he can fit it all in between his new-found promotional responsibilities.

+ Originally published in Real Groove magazine, December 1994.