Ten years ago GARY STEEL wrote a piece detailing the compelling reasons for vegetarianism in the 21st century. In honour of World Vegetarian Month, here it is again.

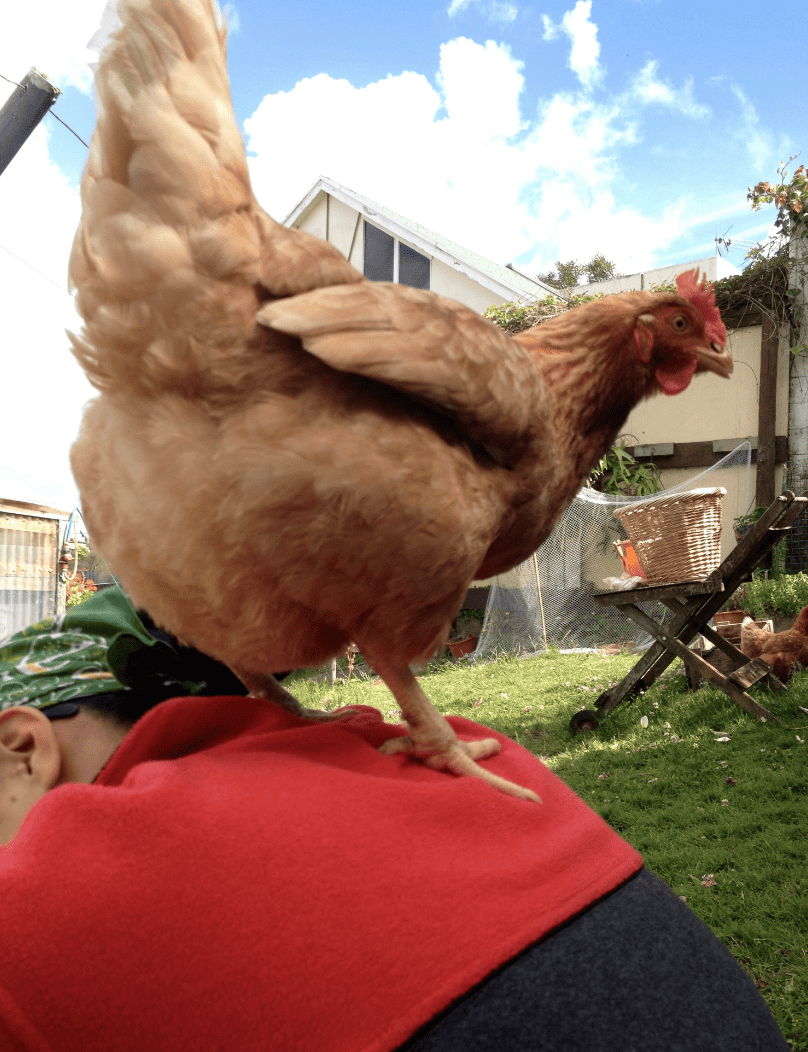

I’M STARING WITH abject horror at a mutant chook. This fat freak, this deformed weirdo carries so much bulk that it can’t walk, its off centre shuffle getting it nowhere, at all. It’s an abomination so shocking that it brings tears to the eyes, and I’m a guy, so I don’t cry easily, okay?

I’M STARING WITH abject horror at a mutant chook. This fat freak, this deformed weirdo carries so much bulk that it can’t walk, its off centre shuffle getting it nowhere, at all. It’s an abomination so shocking that it brings tears to the eyes, and I’m a guy, so I don’t cry easily, okay?

It’s a broiler, one of the untold stories of the poultry industry. Strange that, because most New Zealanders are intimately acquainted with this bird, an everyday cheap feast we commonly encounter on vacuum-packed polystyrene trays in supermarkets, and gobble up in vast numbers. Last year alone, we ate around 100 million of them.

Would you like to support our mission to bring intelligence, insight and great writing to entertainment journalism? Help to pay for the coffee that keeps our brains working and fingers typing just for you. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Riveting writing on music, tech, hi-fi, music, film, TV and other cool stuff. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

Egg makers get all the breaks, it seems. We’ve all seen the shocking coverage of factory egg farms and know something of the hens’ meagre existence, but we know little about the broiler.

Shawn Bishop is giving me a guided tour of the Animal Sanctuary in Matakana, which she runs with her husband Michael Dixon and the help of volunteers. Started in 2002, the facility cares for the most difficult categories of unwanted and injured animals, including native birds. But right now, her focus is on the monstrosity before us.

Shawn Bishop is giving me a guided tour of the Animal Sanctuary in Matakana, which she runs with her husband Michael Dixon and the help of volunteers. Started in 2002, the facility cares for the most difficult categories of unwanted and injured animals, including native birds. But right now, her focus is on the monstrosity before us.

The broiler, she tells me, is bred specifically for human consumption. By selective breeding, today’s broiler is 50 percent bigger than the equivalent bird 30 years ago, and from birth to table the journey takes a mere 40 days. During its short life, the broiler is crammed in sheds with around 40,000 other birds, pumped with high protein feed and antibiotics, and left to fare for itself in the ammonia stink of putrid chicken ablutions. Even when a broiler – like today’s exhibit – is rescued from its pre-ordained fate, its life will be hobbled and vastly curtailed. A normal chook will live for 10 to 12 years, but the broiler is literally too heavy for its heart to cope with the strain, and even in the best conditions, will seldom live for more than a year.

Just when I’m reeling from the inhumanity of it all, Shawn deals her ace in hand. “Ah, but have you heard about the parent bird?” The broiler breeder – or ‘parent’ bird – is a strain of hen specifically chosen for its ability to breed prolifically. Its life consists of being raped repeatedly by especially aggressive roosters and being kept constantly near starvation to keep it laying, and the strain of it all makes its own life as short and brutal as its broiler progeny.

“It’s a secret, shameful industry that nobody seems to know about,” says Shawn.

By this time, all the positivity engendered by the idyllic and expansive farmland surroundings of the Animal Sanctuary has gone down a very black hole, and I’m wondering if the millions of years of human evolution resulting in our smartest monkey status really amounts to jack shit, if we can inflict this kind of suffering on other species.

I FIRST MET Shawn when I dropped by with my wife Yoko, to pick up our first batch of rescued hens early in 2010.

While “rescued” might conjure images of dawn raids on egg farms by militant, nose-ring-wearing lesbian-vegan activists, the reality is more prosaic: when factory-farm hens stop laying for three months at the age of 18 months, they’re normally culled, because this lull in egg-making is considered economically unviable. Groups like Animal Freedom Aotearoa buy the hens using money from donations, and they’re kept at the Animal Sanctuary for six weeks, where the emaciated, virtually featherless birds get a crash course in everything their mother hens should have taught them. Then, the birds go to people who can guarantee a good life in a “non-slaughter” environment.

Watching a factory-reared hen experiencing daylight and grass and open skies for the first time is heartbreaking, because you know just what they’ve missed, and what over three million hens cooped up in tiny cubicles – every year – throughout our golden land never get to experience.

For the first few months, they’re gangly, full-grown babies with ugly, raw necks and skeletal wings and spaced-out eyes. But chickens are tremendously resilient creatures. Unlike humans and all the emotional baggage we carry around from our miscellaneous calamities, chooks rise above memories of the unthinkable tortures they’ve endured, and it’s tremendous fun seeing their personalities bloom when finally experiencing something close to their natural environment.

Not that they’re without scars from their past, however. Their beaks have been carelessly snipped, which makes it hard for them to pick up small food items (like seeds) or tear edible portions from vegetables, and one of my flock is permanently stunted from having been squeezed downwards in a tiny cage.

Caring for ex-factory hens takes time and energy because nobody’s written the book on all the problems that can occur. All the literature is geared towards poultry farms with normal chickens, where any disease that does crop up is dealt a lethal blow with an instant culling. Battery hens are vaccinated and kept on antibiotics for those first 18 months, so a natural environment leaves them vulnerable to serious diseases, most of which are virtually impossible to diagnose.

We had four deaths in the first year, and each time we were gutted, and bereaved. Chooks aren’t affectionate by our standards, but the way they assert their personalities makes them lovable, on their own terms. It’s all been about trial and error, big vet bills and techniques for keeping water and food sources bacteria-free, and figuring out how to keep the others happy when one goes broody for a month… The pay-off is the joy of observing creatures that retain a certain otherness, like feathered versions of Jurassic Park inhabitants. Even birdbrains enjoy stimulus, challenges and human company, and if (as science tells us) pigeons can tell the difference between a Picasso and a Monet, I’m pretty certain my chooks know how to enjoy their time in the garden.

There are so many disparaging words and phrases for chooks – most of them alluding to their perceived lack of brains – that it’s a revelation to discover they’re not the dumb-ass creatures portrayed in literature and cartoons. Sure, the way they strut around with their fluffy bums waddling in the wind is highly comedic, but our historical view of chickens says more about us than it does of them.

Looking at the world through chicken eyes, life is always a drama and always in the present and revolves around food (as it should; their digestive systems, like most birds, demand that they spend most of their lives pursuing and consuming it). The way their vision works gives them certain spatial anomalies that probably benefit them in the natural East-Asian bush setting of their ancestors, but makes them look clueless when navigating the perimeters of a wire fence.

Chickens are so commonplace and undervalued that we haven’t bothered to fully investigate their personalities, the complex and dramatic issues of their social (pecking) order, or even their language. Spend time with a hen, and you hear a vast range of sounds articulated beyond the clichéd clucking, and there’s always some new behaviour to note. Why, just yesterday there was some hot girl-on-girl action in my backyard, and I’m not sure if it was fully consensual.

But it’s not just about chickens. The recent televisual exposes on the welfare of pigs, generated by animal welfare group SAFE, has started a debate around the essential differences between farm animals and “companion” animals like cats and dogs. The problem is, there are none. We pretend that livestock and poultry are somehow intrinsically different by assigning them categories that depersonalise them, because we want to go on exploiting and eating them without pricking our conscience. Cats and dogs, on the other hand, are seen as important because they have a relationship with us, are extensions of our own egos, and mimic human expressions.

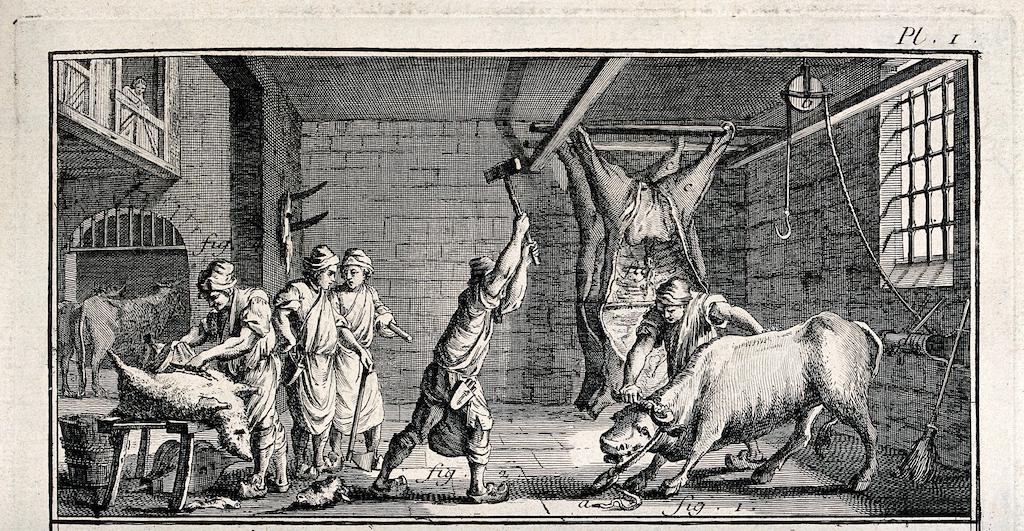

Well, perhaps humans should be given the benefit of the doubt. Just a century back we were slaughtering animals in our own backyards and thinking nothing of it, oblivious to their suffering. Perhaps as a reaction against our instinctive revulsion at animal culling for food, over the past century we’ve devised massive killing houses, which create the illusion that all is cheery.

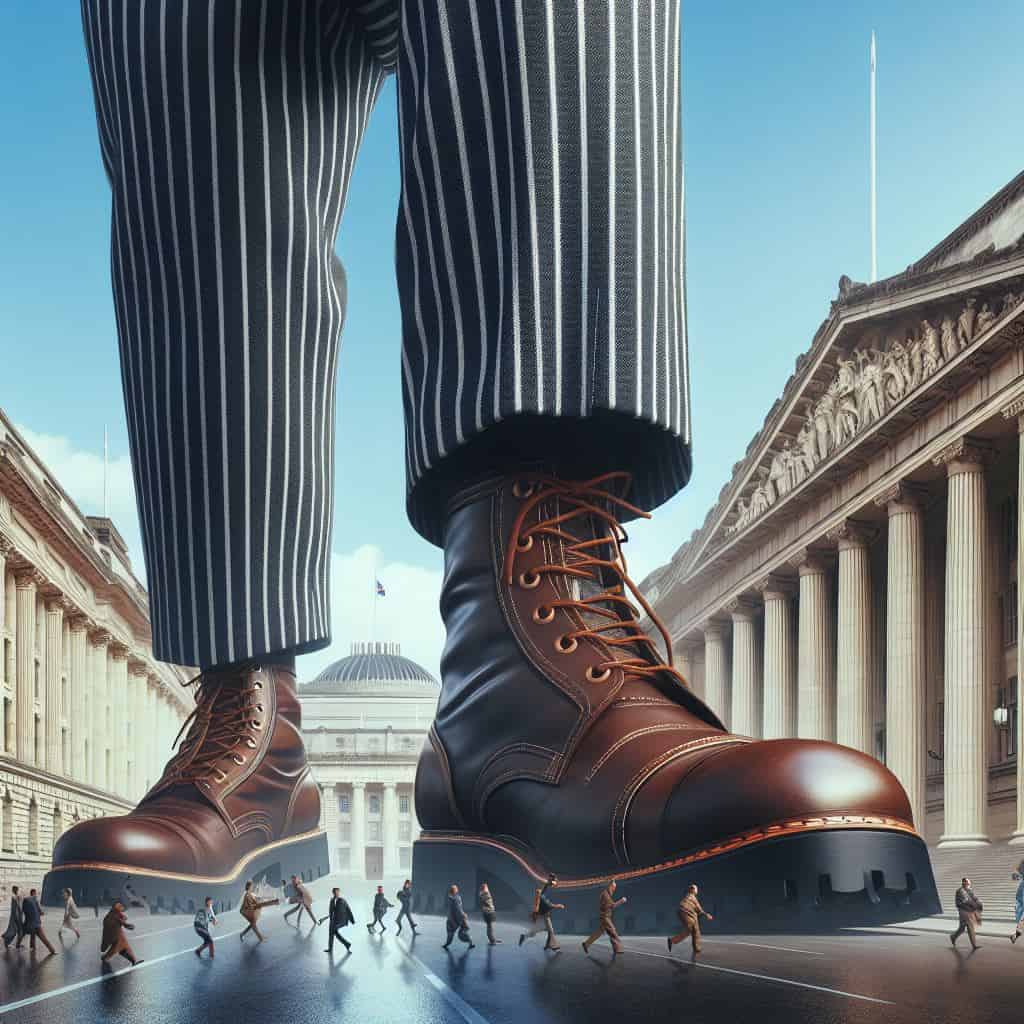

The net result of our squeamishness, however, has created a more pernicious and ever-present evil: instead of acknowledging that our life came from animal death, and counting our blessings for the food, we’ve become ignorant consumers. Meat is now just like any other processed product, and there’s no emotional connection between the buyer, that slab of meat on polystyrene, and its origins as a living, breathing animal that has most likely lived its short life in conditions that would make Nazi concentration camps look civilised.

The net result of our squeamishness, however, has created a more pernicious and ever-present evil: instead of acknowledging that our life came from animal death, and counting our blessings for the food, we’ve become ignorant consumers. Meat is now just like any other processed product, and there’s no emotional connection between the buyer, that slab of meat on polystyrene, and its origins as a living, breathing animal that has most likely lived its short life in conditions that would make Nazi concentration camps look civilised.

This is our shame: that we have allowed intensive industrialised meat production to slaughter in unprecedented numbers, just to satiate our desire for fast and easy food.

BLAME IT ON Kimba The White Lion. As a child of the late ‘60s, while I would voraciously suck the marrow out of bones, I couldn’t be coaxed to chew on vegetables. [Mum, you did used to cook the shit out of vegetables. Sorry]. But then my parents discovered that if I watched that newfangled device – television – during dinner, everything on the plate would vanish, save the plate itself. One of my favourite cartoons was an American-dubbed Japanese animated series later plagiarised by Disney’s The Lion King. In manga artist Osamu Tezuki’s Jungle Emperor (Kimba The White Lion), our hero convinces all the animals in the jungle to stop killing and eating each other and be friends, and just eat plants instead. Improbable and inherently ludicrous as that particular plot development was, it planted a seed that grew through my adolescence as I encountered grown-up texts with vegetarian subtexts, like Herman Hesse’s Buddha parable, Siddhartha. Threatening not to drop out of school in the fifth form, Dad packed me off to the Hutton’s sausage factory, which he promised would be my only job option. A tour of the processing plant transformed me into an A-student.

And then, in my sixth form year – 1977 – I learned that I wouldn’t die if I stopped eating meat, so I did. It had got to the point where every time I chowed down on a sausage or a piece of ham, all I could think about was the animal it came from, and with it came a profound sense of disgust, a realisation that this was a form of cannibalism, and that eating the decaying carcass of another species of animal was little different than killing and eating a human being.

In the 35 years since I stopped eating meat, I’ve not once regretted doing so. Without meat in my gut my constitution improved, and without meat on my tastebuds my palate picked up new flavours. It’s never been a penance, but an edible adventure; an ocean of delicate flavours and a confluence of well-being brought to the table by nature’s larder.

The benefits of vegetarianism were compelling, but it brought its share of pain, too. The mere fact of what for me was a personal choice would provoke scorn and ridicule at dinner parties and barbecues, where I would invariably end up fragrantly smoked by the evenings’ steaks. I grinned, and I beared it, and I kept my head down, but when I got married, my Japanese mother-in-law was outraged. How could you live without meat? How could you make babies?

THERE’S A LOOK of amused incredulity on Green Party co-leader Russell Norman’s face. Poor old Don Brash has just made another one of his horrendous gaffes, and there’s mocking laughter from the floor.

It’s the minor parties’ leaders’ televised election debate, and Brash has just given his unintentionally darkly comedic two cent’s worth on the Emissions Trading Scheme:

“Most of the carbon dioxide emitted by animals comes from eating grass. Where does the grass get the carbon from? From the atmosphere!”

Poor sad Brash doesn’t quite get the fact that for millions of years, NZ’s pristine bush scape was devoid of cows and sheep.

What stays off the agenda – even in real debates – is the more perplexing, and deeply troubling, issue of modern agriculture itself, which is by its very nature (if I hazard to even use that word) polluting and unsustainable.

The evidence is pretty conclusive that a shift away from intensive agriculture and into horticulture by developed countries would have a massively beneficial impact on environmental health. The rub? It would mean radically cutting back on our consumption of meat.

But despite overwhelming data that diets low in meat, or completely sans meat, result in healthier people, this option is clearly not being explored.

Instead, John Key has proudly publicised his government’s multi-million dollar investment in technology that will supposedly minimise those nasty belching, farting bovines, while ignoring the other glaring issues around modern farming: the leeching of polluting phosphates from farms into rivers, the trans fatty acids in meat that cause us so many health problems, and of course the welfare of NZ’s farm animals.

A core component of the NZ populace is clearly keen to see our environment protected, and there’s a remarkable increase in the response to this perceived market in business. Despite Fonterra’s inexplicable binning of its organic milk suppliers, there’s a huge growth curve in organic products, and interest in free-range eggs and locally grown products fresh from the gate. This has in turn been reflected and promoted by a tsunami of “green” media.

I’VE MET SOME really stupid vegetarians over the years. The kind that reckon it’s wrong for Eskimos to hunt seals and eat them, even though there’s no alternative source of protein. Or the kind that reckons it’s better to pollute the environment making synthetic materials than to wear leather. These are tricky ethical waters, and nobody’s going to ever be in total accord over the details.

But the truth is this: Western nations are living in a bubble of consumerism (literally the fat of the land) while most of the populous nations starve. We no longer need meat to live or be happy, and the planet is healthier when it’s not straining to “grow” meat.

What’s holding us back? One word: nostalgia. We grow up being fed certain foods, and because we’re naturally nostalgic creatures, we yearn for those comfort palliatives, especially in times of stress. I’ve known so many males who would give up meat except for the fact that they couldn’t possibly live without bacon. But really, the same people would probably have said the same thing about cigarettes a decade ago. And the previous generation wouldn’t have countenanced getting home to the “missus” without getting blotto in the six-o-clock swill first.

One genuinely amazing thing about humans is that we can, and do, change. We can make our minds up about something, and just do it. And our teeth and digestive system errs on the side of vegetarianism, even though it’s built to accept an omnivorous diet, just like our close cousin, the chimpanzee.

Meat propaganda flourishes everywhere in NZ, claiming that dead flesh is the best source of iron, or the only complete protein, and it’s rubbish. A classic example of such misinformation can be found in the latest issue of Alive magazine, in which Lynda Hallinan repeats the trope that: “Meat is an essential source of iron for brain development and energy, and babies should be offered meat three to four times a week.”

Tell that to the many millions of happily, healthily vegetarian and vegan families around the world.

There’s evidence that the eating of meat played a part in our evolution, contributing to the clever and wily creatures we have become. But there’s no evidence that, should we become vegetarian, that we would descend down a slippery slope back to our primeval past, becoming masticating morons in the process.

John Robbins, who kicked the whole vegetarian-as environmentalist movement into life in the 1970s with Diet For A New America, recently wrote a book, Healthy At 100, which studied different cultures around the world, their dietary habits and longevity. Without exception, cultures with incredibly low meat consumption – for instance, the native peoples of Okinawa – were the healthiest and most long-lived. But those same cultures were now experiencing a huge health decline linked to the invasion of heavily meat-oriented Western food and fast food outlets like McDonalds.

But health be damned, this is really about a new way to look at animals. Amazingly, my parents’ generation took the Bible literally when it stated: “So man shall have dominion over the earth and all its creatures” (paraphrased). This view, that humans were somehow apart from nature, as the sons (and spare ribs) of God, and had power and superiority to wield over the creatures and the environment, is (thank God!) slowly evaporating.

A new perspective was detailed by Steven M. Wise in his acclaimed book, Rattling The Cage, in which the author exposed the essential illogic of human thinking in regards to other species. Wise’s contention was that animals should be considered “people” – not “things” to own and exploit – and therefore should have rights under human law.

Now that we know that animals have sentient brains, complex emotions and the will to live and carry out their natural imperative, it’s surely time for the human species to start to overcome our biggest blind spot; the one that’s tied to our considerable egos, and the one that puts our own species at the centre of the universe.

- This story was originally published in Metro magazine.