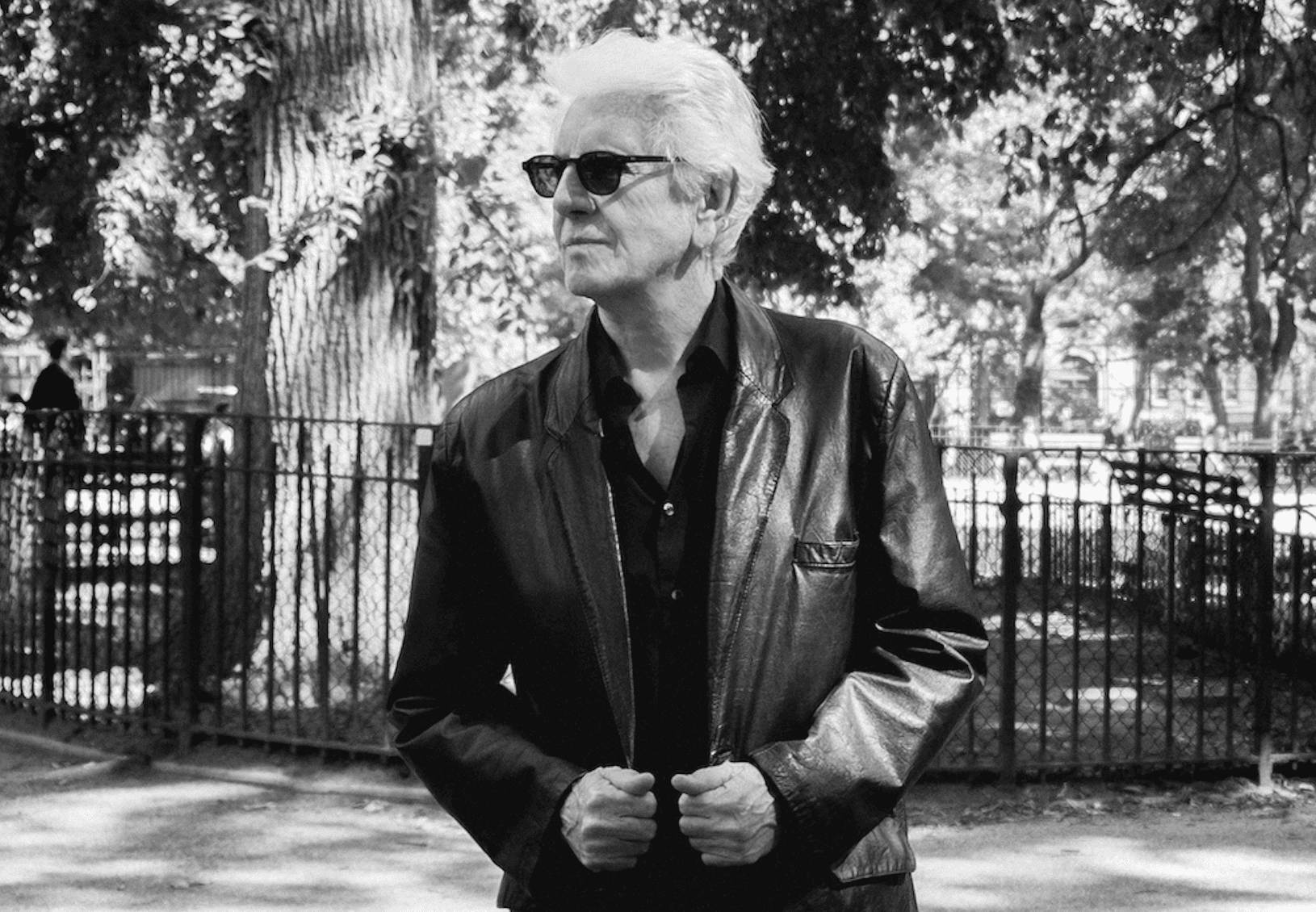

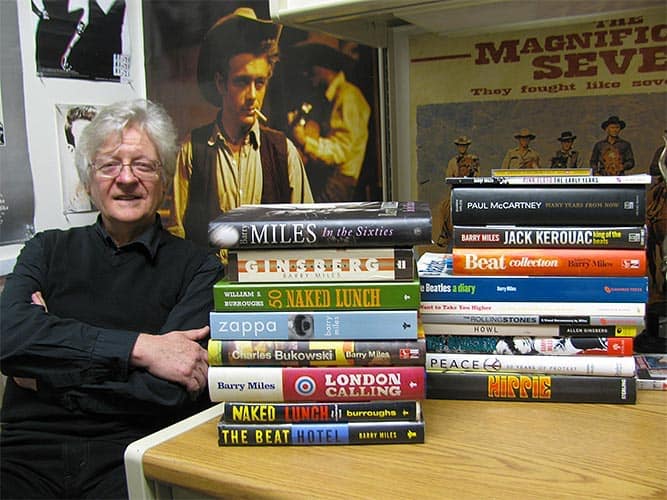

The psychedelic revolution flamed into the Summer Of Love in 1967 and Barry Miles was in the thick of it. GARY STEEL interviews the author.

Watch out, kids! If your parents were teens or 20-somethings in 1967, they may be keeping some dark secrets from you – tales of rampant drug use, free sex orgies and running wild.

Then again, they may just be normal, run-of-the-mill parents who, like all but the lucky few, weren’t even aware of the psychedelic revolution when it was in full flower.

Despite its persistent hold over the imaginations of successive generations, the original exponents of the psychedelic revolution were a subculture tiny in number and covert in lifestyle, one of the reasons writer Barry Miles still avoids the “psychedelic” tag, preferring to describe the ‘60s phenomenon as the “underground movement”.

He should know. Miles was a seminal figure right from the first flourish of what would later be dubbed the psychedelic revolution, giving him a unique perspective on its development from a genuine countercultural movement through its popularisation, commodification and inevitable fragmentation.

He should know. Miles was a seminal figure right from the first flourish of what would later be dubbed the psychedelic revolution, giving him a unique perspective on its development from a genuine countercultural movement through its popularisation, commodification and inevitable fragmentation.

Thirty years later, Miles has contributed a lucid account of the psychedelic era for a coffee table book, subtly titled I Want To Take You Higher.

Support Witchdoctor’s ongoing mission to bring a wealth of new and historic music interviews, features and reviews to you this month (and all year round) as well as coverage of quality brand new, contemporary NZ and international music. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

Originally an essay commissioned to tie in with a psychedelic exhibition at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame And Museum (catchy name, that) in Cleveland, Ohio, Miles ended up providing the London perspective of the book, which together with Charles Perry’s San Francisco slant, gives the reader a fascinating chronological insight on the years 1965-69.

Invaded as we are by the fat hand of America, San Francisco has become synonymous with the birth of the psychedelic revolution, but Miles knows better: It began on the streets of London. He was one of the organisers of the original event, the Poets of the World/Poets of Our Time poetry reading at London’s Royal Albert Hall in June 1965.

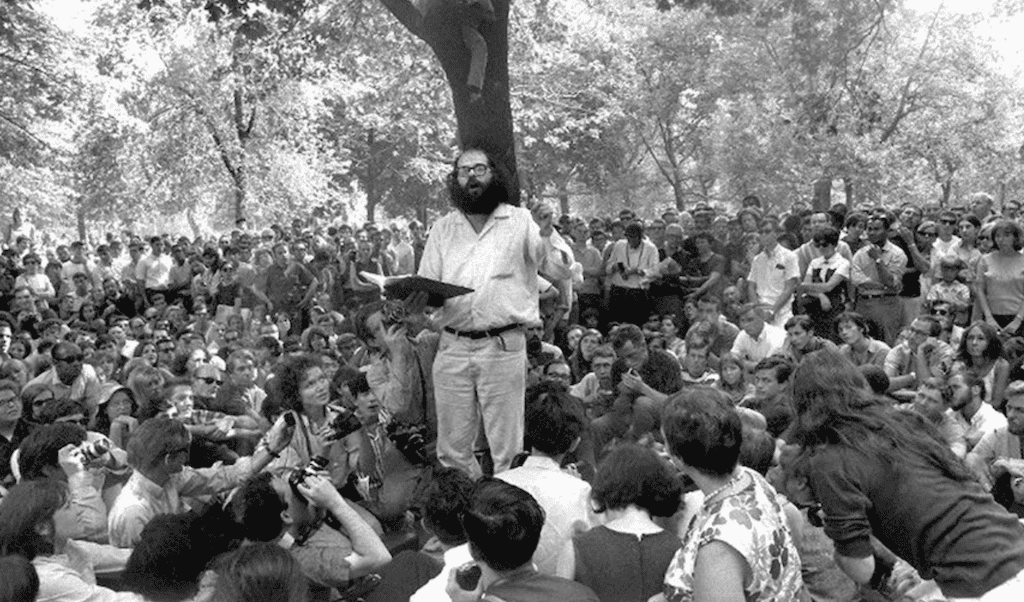

Long before there was a musical style to reflect the new mindset, this event signalled the new scene. Miles writes: “As the audience arrived, they were handed flowers by prototypical flower children who had their faces painted with paisley patterns. Incense and pot smoke wafted. A dozen bemused schizophrenics brought along by psychiatrist RD Laing blew bubbles and danced to music heard only in their own heads. The featured poets were Gingsberg, Ferlinghetti and Corso. At one point Dutch poet Simon Vinkenoog, high on acid, snatched the microphone and ran around the hall screaming ‘Love, love, love…’”

The psychedelic revolution emerged from a literary scene – the beatnik poetry of Allen Ginsberg and the wilting observations of William Burroughs were integral – before there was a musical expression to suit, says Miles.

“The original post-war Bohemian was given form by the ‘beats’, so the original people involved in the English underground were all very influenced by the ‘beats’. Burroughs was living in London at the time, and his friends who were involved in the early events were all writers.

(Miles now says of the elderly Burroughs: “He’s in good shape, considering how much he drinks and how many drugs he takes. He’s in Lawrence, Kansas, with his cats and his paintings and his shooting, and as long as he doesn’t fly around and get tense, he’s okay.”)

“There were very few musicians around in the early period. I think the reason the whole scene is so identified with music is that music is the main thing that got marketed. That was the main thing that modern capitalism could get its hands on and turn into something it could sell, so in the end, the whole scene just became music, but certainly, in the mid-‘60s it was a whole variety of things.”

Ginsberg – who was later immortalised for shoving a flower down the rifle of an American soldier and coining the phrase “flower power” – died a few months ago.

“Allen called me literally a day before he died,” says Miles. “I had a long talk with him… he knew he was dying but he’d come to terms with it and in fact he was happy.”

Miles owned Indica Books, one of the focal points and meeting places for the new scene. Ginsberg hung out there. Frank Zappa used it as his London office. Paul McCartney designed the wrapping paper.

“He did it quite nicely, says Miles. “He turned up with this gigantic package. It wasn’t exactly art paper, but it wasn’t exactly wrapping paper, either! I wanted to frame it rather than wrap stuff up in it. And then one of the American teenybopper magazines reproduced a picture of it and we had millions of letters from American fans asking for the wrapping paper.”

Despite participation from big stars like McCartney, the scene was without a voice. The first rumblings of the “underground press” – the legendary International Times – were heard via Miles and Indica, and the formation of the formative psychedelic venue, UFO, was integrally connected to both.

“The regular press didn’t cover rock’n’roll. The Beatles might get covered, or the more spectacular outrages of the Rolling Stones, but you didn’t get the regular coverage of popular culture. That’s why we had to start the underground press. No one would do a serious interview even with someone like John Lennon.

“There weren’t the publicists and management in those days, and all the interviews I did I would simply ask the people to come to my place, or else I’d go to their house.

“These days MTV and endless hype has reduced the value of the work, but back then a new album was a big thing, and people listened really carefully. The underground press, the underground albums, and underground exhibitions, that was really IT, the source of communication in our community.

“But of course, one could just go down to see Jimi Hendrix playing in a tiny club somewhere, and even The Who… no one would have recognised them in the street in ’67. It was such a small scene, and there was nothing much about it in the press or on TV or radio.” International Times “was very much a volunteer thing. Most of the people didn’t get paid, and the full-time staff had to work at the UFO club at weekends to earn some money.”

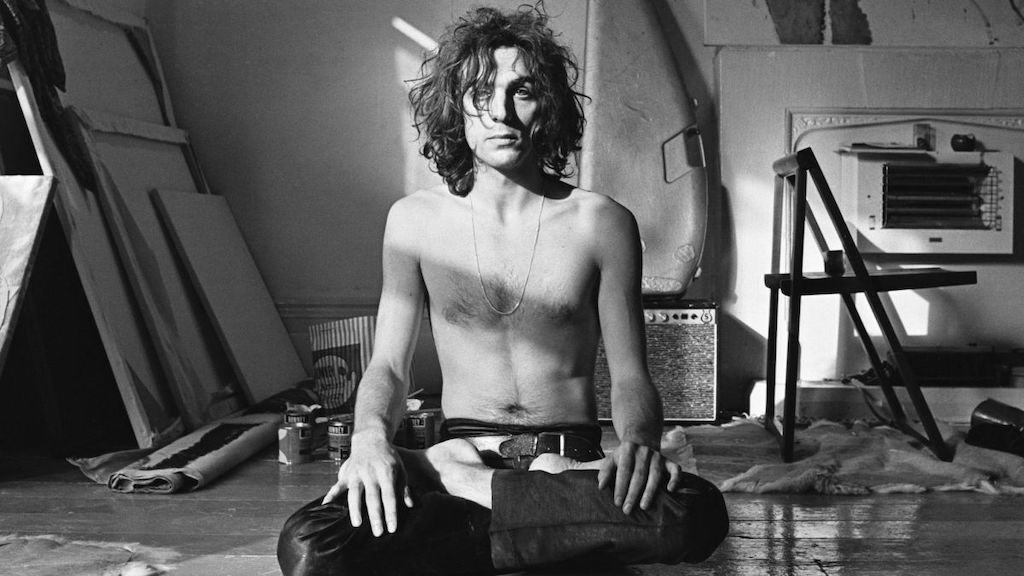

UFO is now remembered as the club that catalogued the first stirrings of English psychedelia, with regular performances by The Soft Machine and Pink Floyd, for a brief time awash with LSD-fuelled creativity.

In I Want To Take You Higher, Miles notes that Pink Floyd’s enigmatic leader, Syd Barrett, lived for a year in a flat with a glass that was constantly spiked with LSD. “Yes it’s true, and it’s probably why he’s still a vegetable,” says Miles. “I suppose nobody was aware of that at the time, because there hadn’t been any acid casualties at that point.

“But I think John Lennon was heading in that direction, too. He took a tremendous amount of acid, and there was one point where he called a meeting of The Beatles at Apple headquarters and announced that he was Jesus Christ. ‘Well right you are John, we’ll bear that in mind!’

“Had Yoko not turned him on to heroin, he would have probably turned into an acid casualty, because he was really out there. Being John he’d done a really good job on it. You’ve got to get rid of your ego, right? So he smashed his to pieces. Fortunately, there were enough people around to help him put it together again.”

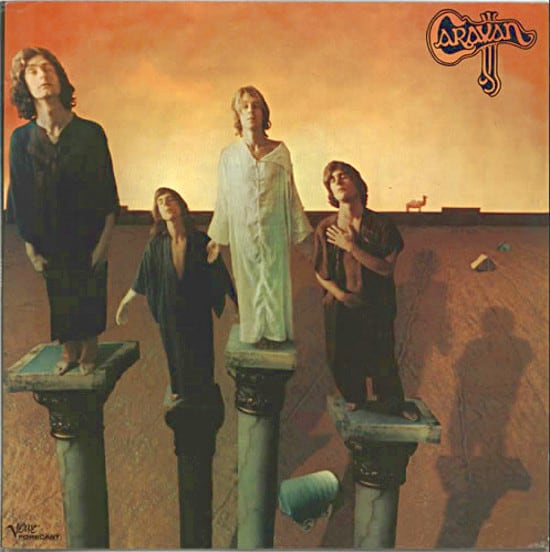

The writer’s own drug use is fairly obvious on his liner notes for a 1969 album by hallucinogenic hippy band Caravan: “The flute playing Sahara bird-flight solos hovering over the camel-train, earth magic, soft machine and sky. It’s nearer to us than Africa though… lift the yashmaks & see: Loplop, the Superior of the Birds, little bubble of sound breaking through dry sand.” Etc.

The writer’s own drug use is fairly obvious on his liner notes for a 1969 album by hallucinogenic hippy band Caravan: “The flute playing Sahara bird-flight solos hovering over the camel-train, earth magic, soft machine and sky. It’s nearer to us than Africa though… lift the yashmaks & see: Loplop, the Superior of the Birds, little bubble of sound breaking through dry sand.” Etc.

“They don’t make any sense,” admits Miles, when I remind him of this obscure purple passage. “I don’t know what I was on when I wrote that!”

Miles is far from “down” on drugs, crediting LSD experimentation with a good deal of the creative brilliance and exploration of the psychedelic era. But he’s disappointed. “It’s a pity it turned into such a bête noire. It could have been much more use to society instead of just a recreational drug, which is what it turned into. That was partly to do with its popularisation on the West Coast of America. On the East Coast, you had the Ginsberg and Tim Leary side, who saw it as a spiritual thing, expanding people’s consciousness and awareness, whereas on the West Coast you had Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, who were just doing it for fun.

“It turned into tremendous peer pressure. People were constantly spiking each other, and it became quite an unpleasant thing. There was tremendous one-upmanship about how much they’d taken and how much they could deal with… ridiculous posturing.”

Despite the prominence given to San Francisco in I Want To Take You Higher, Miles is unimpressed with its claim to psychedelic immortality, especially in regard to the music the city produced.

“We’d never heard any of the stuff coming out of San Francisco. None of those bands made any records until late ’67, and their early albums are pretty bad. We were far more interested in the Los Angeles bands. We liked Frank Zappa, The Doors, The Byrds, Love. LA was far more important, and also of course New York, which we regarded as the cultural capital of America.”

“We’d never heard any of the stuff coming out of San Francisco. None of those bands made any records until late ’67, and their early albums are pretty bad. We were far more interested in the Los Angeles bands. We liked Frank Zappa, The Doors, The Byrds, Love. LA was far more important, and also of course New York, which we regarded as the cultural capital of America.”

For Miles, life isn’t stuck in the psychedelic era, but his roots are always showing. In 1970 he packed his bags and headed for New York, where “I went and lived on Allen Ginsberg’s hippy commune in upstate New York, and did a lot of work with Allen… cataloguing his tape archives, producing an album of him singing William Blake for The Beatles’ spoken word label.”

Subsequently, he worked for William Burroughs, wrote for Crawdaddy and Rolling Stone, and wound up back in England in 1976, writing for New Musical Express and editing Time Out. In the ‘80s he wrote an Allen Ginsberg biography and, “for the last five years I’ve been working on a book with Paul McCartney about the ‘60s. It should finally be out in October… It’s based on about 14 interviews with him, and concentrates entirely on the period ending in 1970.”

Miles states baldly that it was McCartney – not Lennon – who explored the psychedelic landscape. It was McCartney who turned on to LSD first, and whose musical experiments resulted in the classic psychedelic albums Revolver and Sgt Pepper.

“A lot of people don’t realise. They always think that John was the avant-garde member, but that wasn’t until he got together with Yoko, which was quite late.”

It’s a measure of the respect that many of the leading lights of the ‘60s have for Miles that they are willing to open up in a way that they would never do with a conventional journalist. “When I wrote the Ginsberg biography, he gave me complete access to all his personal journals and archives, his most intimate scribblings, and he didn’t impose any restrictions,” says Miles.

The McCartney project was slightly different, but ended happily: “He wanted to read it after I’d written it, and make suggestions, cuts and changes. The deal was that he’d tell me everything, and we’d go over it later, rather than him trying to self-censor at the interview stage.

“He cut out far less than I was expecting… there’s still a huge amount about drugs, John Lennon and stuff which I thought might be cut. But he didn’t.”

* This story was originally published in the Sunday Star-Times on July 20, 1997.