Neill Duncan, who died late last month, is an undersung hero of NZ music. GARY STEEL compiled this appreciation.

The first thing I did when I heard that Neill Duncan had died was search for his entry on Wikipedia, except there wasn’t one.

The first thing I did when I heard that Neill Duncan had died was search for his entry on Wikipedia, except there wasn’t one.

I was enraged. Even losers in TV talent contests get Wikipedia entries. And then reality kicked in, and it got me thinking. In my musical psychogeography Neill was a genuine star, but in his 40-odd years of music-making – first in Wellington, then in Auckland, then in New South Wales – his philosophy was unfailingly community-based and collaborative. He never seemed to overtly seek fame or his name in lights.

That made him almost an oddity in the shiny, marketing and promotion-obsessed 21st Century. And society’s obsession with novelty meant that it was his first bout of cancer and the amputation of an arm at the elbow in 2012 and his subsequent reinvention as “the guy who plays the saxophone with one hand” that he became most well-known for.

Would you like to support our mission to bring intelligence, insight and great writing to entertainment journalism? Help to pay for the coffee that keeps our brains working and fingers typing just for you. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

He was never a close friend, so why did his death hit me so hard? In my 45 years of music journalism I’ve never interviewed him, and never consciously assessed his worth to the local music scene, but in truth, he was the kind of individual – and prodigious talent – that turns up everywhere to add creative sparkle to projects.

My first experience of Neill was as a fan of Wellington free jazz ensemble Primitive Art Group, which he joined shortly after moving there in 1981. They were astounding to witness in concert and Neill’s contribution to the group was immense, both musically and visually. He was a striking, handsome chap blasting away on his sax and although the group was very much about performing as equals the eye tended to rest on Neill with his impressive crop of hair.

Wellington in the early 1980s was saturated with the austere nihilism of post-punk but somehow, the Primitive Art Group fit well into this scene and when they performed amongst loud rock groups at a music festival I covered for TOM magazine in 1983 their blend of organic cacophony sounded perfectly complementary. (Note: keep an eye out for a forthcoming book on the group).

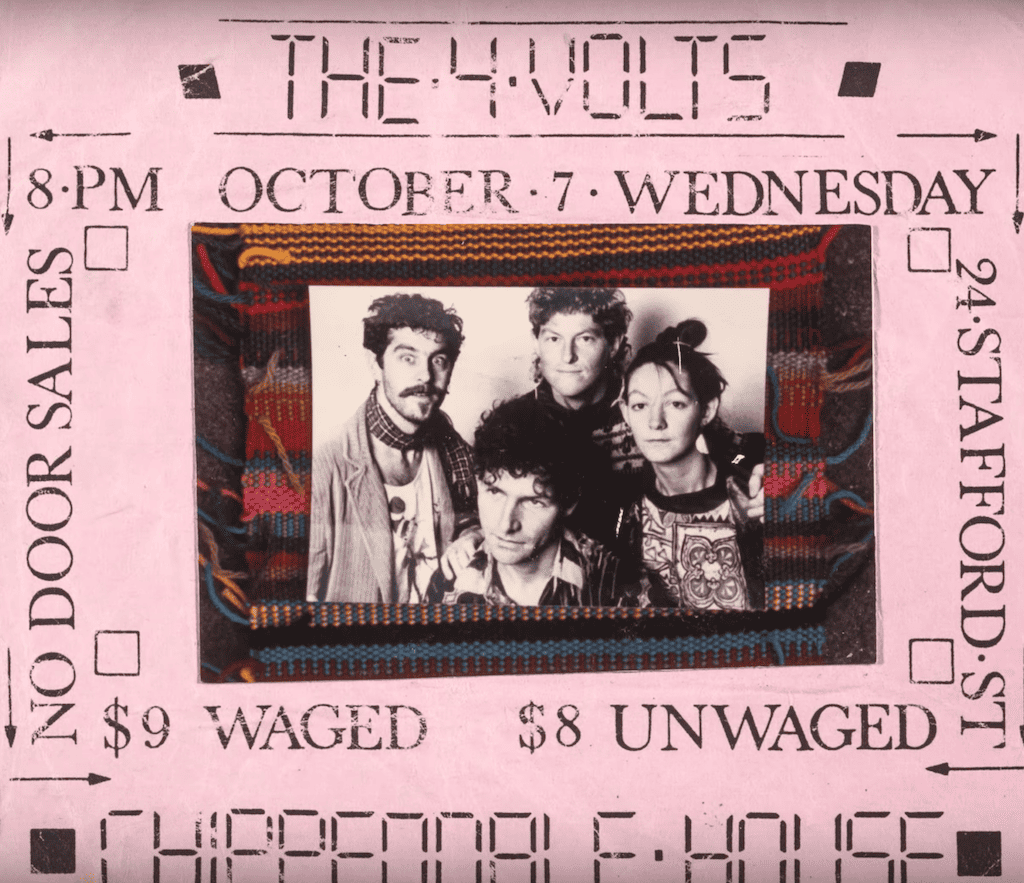

Later, Neill went on to perform with offshoots of PAG like the idiosyncratic Six Volts and for a time, joined The Spines, a group revolving around the songwriting of guitarist/vocalist Jon McLeary, but which constantly evolved its hybrid blend of rock, pop and whatever else depending on its lineup at the time.

What I didn’t realise back then was just how open-minded Neill was to different music. I got a glimpse of that in Auckland in the ‘90s, however, when he was involved with a loose collective of musicians formed in tribute to both Duke Ellington and Sun Ra; and later, when he would call into my “weird music for weird people” record shop, Beautiful Music, and we’d have conversations about far-out music. It seemed to me that – while he had a particular love for avant-garde jazz – he was open to just about anything as long as it involved genuine collaboration and had some kind of community orientation.

While I was running my record store, Neill released his one solo album, Quiver, in 1999 through the Braille label run by his former cohorts in PAG. It received very little publicity but stands tall as an album that does really espouse something of his musical aesthetic. Neill sings and plays guitars, drums, accordion, harmonium, synth, clarinet, alto sax, harmonica and percussion on the record. While it features a few of his old musical cohorts (Anthony Donaldson, Dave Long, Janet Roddick) he also brings in a couple of more electronically inclined artists like Steve Roche and Ben Harris. If anything, the result is more like a Chris Knox album than something from the jazz world.

While I was running my record store, Neill released his one solo album, Quiver, in 1999 through the Braille label run by his former cohorts in PAG. It received very little publicity but stands tall as an album that does really espouse something of his musical aesthetic. Neill sings and plays guitars, drums, accordion, harmonium, synth, clarinet, alto sax, harmonica and percussion on the record. While it features a few of his old musical cohorts (Anthony Donaldson, Dave Long, Janet Roddick) he also brings in a couple of more electronically inclined artists like Steve Roche and Ben Harris. If anything, the result is more like a Chris Knox album than something from the jazz world.

While living in Auckland, he also performed with The Jews Brothers and The Blue Bottom Stompers. It’s this musical breadth and community engagement that makes Neill Duncan important. He had his hands on so many different projects but never boasted about them. A good example of this was outlined by Wellington musician/producer Mark Austin, who wrote eloquently on his Facebook page about Neill’s contribution to some of his projects.

“I first met Neill in early 1981,” writes Mark. “We had the common background of training as teachers but leaving it for music. Neill had a lot of charisma and I still remember his jokes and repartee from the first dinner I shared at their flat. He had extremely diverse musical interests and influences and mixed up genres both in what he listened to and what he played. He also had an infectious flair for performance and an innate ability to educate as he played.

“The Primitive Art Group was an astounding bunch of experimental free jazz musicians that were influential in creating what is still a very healthy and advanced avant-garde and free music scene in Wellington, but their accessibility was aided greatly by Neill’s charisma and ability to both entertain and educate while performing serious experimental music. At the same time, his extraordinary sax work in The Spines took them (and us) to an altogether different planet, bringing in elements of free jazz, while sitting in the melodic rock format. If Jon dared to say “we don’t need sax in this tune mate”, Neill would respond “cool, I’ll just play cowbell” and the audience would be treated to an equally spectacular and educational cowbell solo that would again explore the limits of the instrument. Neill was engagingly enthusiastic and there was no holding him back!

“At this stage, he was very much a live performer and improviser, whereas my strengths were more as a composer of formalized work. Despite this difference in approach, Neill found the time to show respect for my work and visited me often, giving me positive feedback and propping me up, for which I am truly grateful. He was always generous and would provide thoughtful gifts – often records that would expand my musical frontiers.

“The Six Volts took off while I was living overseas and we caught up with their artistic success at the Edinburgh Arts Festival in 1989, along with The Front Lawn, whose first album the Volts also played on. In this group of talented individuals, Neill’s charisma still stood out.

“I formed a soundtrack company with David Long in Auckland in 1991. When David and I teamed up with Don McGlashan on a feature film in 1992, we flew Neill up to play sax and clarinet solos. Later that year, Neill proposed he and I team up as musical directors of Cabaret at the Watershed Theatre. It was a fun band – we did abstract readings of the score and it was a very successful show – the first of many for Neill and me. Neill and I collaborated on a number of soundtracks for theatre shows (including Simon Bennett’s Titus Andronicus, Michael Hurst’s Hamlet, and Inside Out’s A Spectacle Of One) and we worked together on many individual projects before combining to write, direct and perform the music for Braindead The Musical (aided by Jeremy Jones, Russell Scones and the whole cast) in 1995 – a huge undertaking and a critical success!

“I formed a soundtrack company with David Long in Auckland in 1991. When David and I teamed up with Don McGlashan on a feature film in 1992, we flew Neill up to play sax and clarinet solos. Later that year, Neill proposed he and I team up as musical directors of Cabaret at the Watershed Theatre. It was a fun band – we did abstract readings of the score and it was a very successful show – the first of many for Neill and me. Neill and I collaborated on a number of soundtracks for theatre shows (including Simon Bennett’s Titus Andronicus, Michael Hurst’s Hamlet, and Inside Out’s A Spectacle Of One) and we worked together on many individual projects before combining to write, direct and perform the music for Braindead The Musical (aided by Jeremy Jones, Russell Scones and the whole cast) in 1995 – a huge undertaking and a critical success!

“Neill played the most wonderful clarinet and sax on some of my compositions in subsequent years. I followed his many pursuits after he moved to Australia and relished our catch ups and holidays together on his NZ visits and tours. I’ve enjoyed meeting his vibrant children and I can only imagine how much they will miss their Dad. Neill has also been a significant mentor to my son – among other things, helping him learn how to “swing” with his drumming. Neill’s eye for clothes also needs to be mentioned – he had a real taste for the whacky, and I always appreciated his extreme (but tasteful/wearable) dress sense.

“Neill’s generosity of spirit, his attentiveness to others’ feelings – and perhaps above all – his magic, intelligent sense of humour and of the expansiveness of life, have been ever-present. He amazed us all with his “it’s only a flesh wound” Monty-Pythonesque ability to carry on playing sax after losing his arm – proving, as he always said, that music is not about technical dexterity – it’s the musicality that guides the playing that creates the magic. And a great magician-musician he was! He has been a huge influence in my life and a very significant friend whom l will miss enormously.”

Mark’s tribute sums up nicely the intrinsic value of this man and his music and what we’ve lost now that he’s gone. Of course, he spent the last decades of his life living in New South Wales, during which time he doubtless became as loved and appreciated as he was in New Zealand.

Mark’s tribute sums up nicely the intrinsic value of this man and his music and what we’ve lost now that he’s gone. Of course, he spent the last decades of his life living in New South Wales, during which time he doubtless became as loved and appreciated as he was in New Zealand.

The Blue Mountain Gazette’s appreciation of Neill notes that in 2002 he moved to Australia, first to Bondi where he started a family with his first wife, Rachel, and became an exceptional teacher “renowned for his gift of communicating with young people.

“He taught at Emmanuel School in Sydney, before moving to the Mountains in 2004 and teaching at Blue Mountains Grammar, Penrith Adolescent Centre, and Korowal School, where he led the band, Neill’s Armee.

“Neill was a well-known performer in Sydney, as well as in the Blue Mountains, and played with Darth Vegas, Christa Hughes and The Surgeons, and The Snaketown Rattlers, which for a decade closed the Winter Magic After Party at The Carrington.”

When Neill lost his left arm in 2012, “he was able to connect with Maarten Visser of Flutelab in Amsterdam, who developed a one-handed tenor saxophone and a one-handed soprano saxophone,” according to the Blue Mountain Gazette. “He formed The Three Handed Beat Bandits with guitarist John Stuart and started gigging again, producing an incredible sound as he played both sax and drums with just one hand.” He was also invited to give a special performance at the 2015 World Saxophone Conference in Strasbourg.

When Neill lost his left arm in 2012, “he was able to connect with Maarten Visser of Flutelab in Amsterdam, who developed a one-handed tenor saxophone and a one-handed soprano saxophone,” according to the Blue Mountain Gazette. “He formed The Three Handed Beat Bandits with guitarist John Stuart and started gigging again, producing an incredible sound as he played both sax and drums with just one hand.” He was also invited to give a special performance at the 2015 World Saxophone Conference in Strasbourg.

“Neill had found a new career as an advocate for recognition of the rights of disabled people to access the tools to fulfil their talents and became a nationally recognised speaker for disability services up until a month before his death.

“In 2016, Neill was invited to become part of the ‘We Are The Superhumans Band’ and recorded at the legendary Abbey Road Studios for the Rio Paralympics.”

Diagnosed with virulent lymphoma in June 2021, Neill died on December 28, 2021, two days after his wedding to Naomi.

* Neill Duncan – March 9, 1957 to December 28, 2021.

+ Feature pic (top of page) credit: Leahy & Watson.

A lovely and very accurate tribute, thank you Gary.