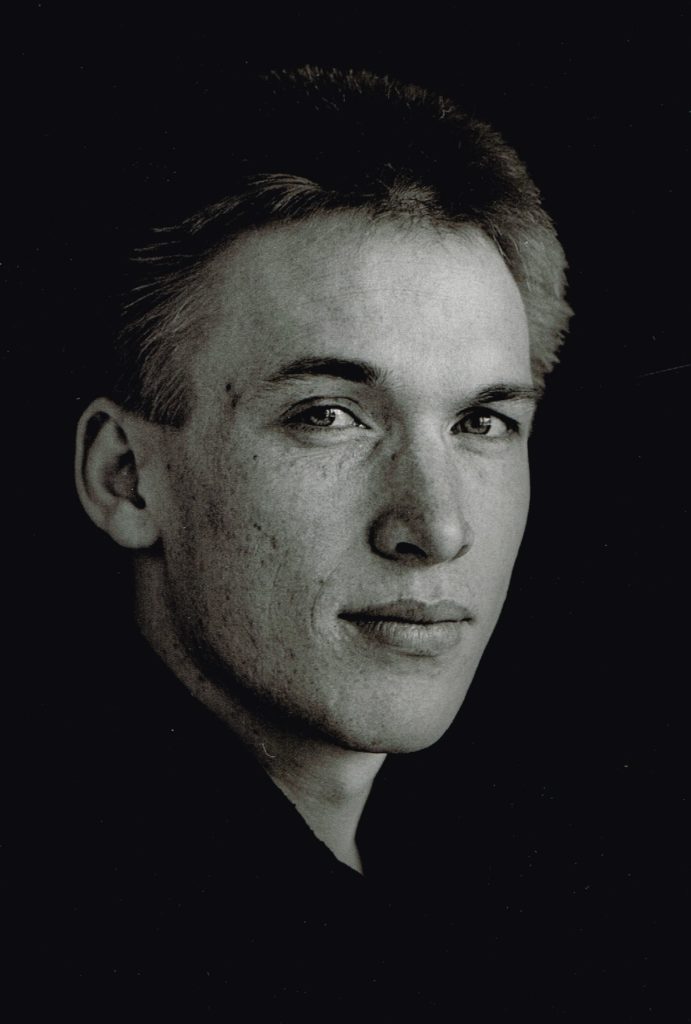

In 40 YEARS IN 52 WEEKS, GARY STEEL trawls through his archives to celebrate a lifetime of writing about modern music, and pens some new perspectives to mark the occasion. The subject of today’s piece: 1979.

Nineteen seventy-nine was a great year for music, and for many, it was a high-water mark. It was also, for me, the first of 40 years of writing about music, and a never-ending stream of album reviews.

Nineteen seventy-nine was a great year for music, and for many, it was a high-water mark. It was also, for me, the first of 40 years of writing about music, and a never-ending stream of album reviews.

It was a flawed and faltering start, however, and I hardly got to pass comment on any of the now-iconic releases from that peak year of post-punk pursuit.

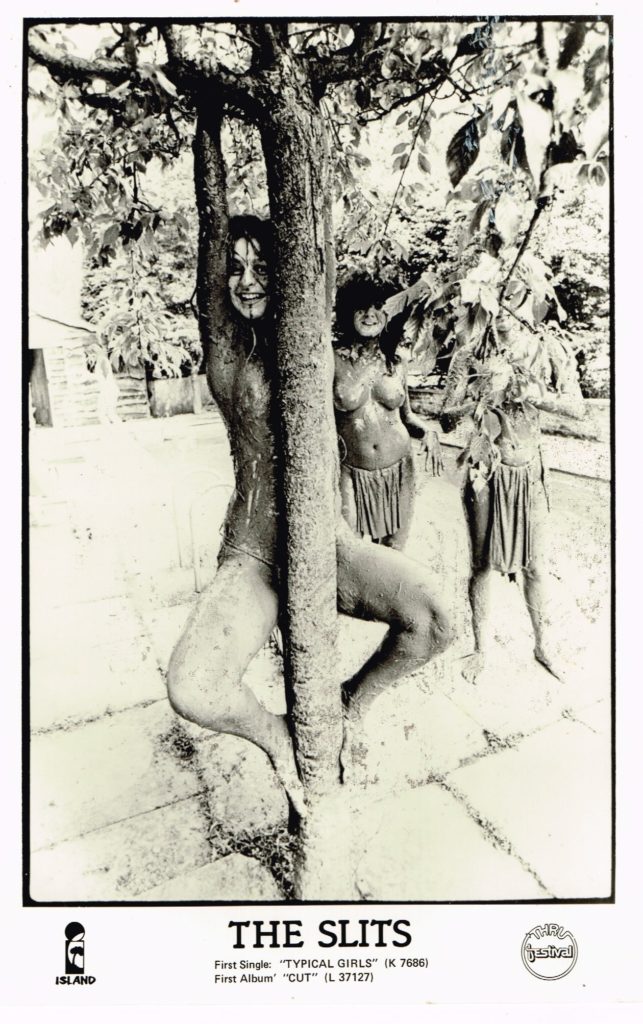

Let’s just take a minute to consider how very great 1979 was in terms of creativity arising from what only two years previously had been the raw, primal and rather limited spit and venom of punk: Throbbing Gristle’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats, Wire’s 154, Public Image Ltd’s Metal Box, Gang Of Four’s Entertainment, Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, The Pop Group’s Y, The Slits’ Cut, The Cure’s Three Imaginary Boys, Magazine’s Secondhand Daylight, Pere Ubu’s New Picnic Time, Siouxsie & The Banshees’ Join Hands, The B52s’ The B52s, Talking Heads’ Fear Of Music, Marianne Faithful’s Broken English, Buzzcocks’ A Different Kind Of Tension, Gary Numan’s The Pleasure Principle, XTC’s Drums & Wires, Devo’s Duty Now For The Future, YMO’s Solid State Survivor, The Damned’s Machine Gun Etiquette, The Human League’s Reproduction…

I could go on, but it might be a little tough on your digestive system.

Meanwhile, my first published words on music took place in May 1979, and included album reviews by the likes of The Shirts, Night, Tycoon, Skids, The Alan Parsons Project, Kansas, Little River Band, Foxy, The Sinceros, The Sutherland Brothers and Foreigner.

Everyone has to start somewhere, of course, and I basically took what I was given.

The previous year I’d taken the Wellington Polytechnic Journalism Course and just scraped through. I’d hated every minute of it, and whenever I could, I’d slink off and play hooky by going to afternoon double features of old movies at The Paramount. It just wasn’t what I’d signed up for. If there had been a creative writing course back then, that’s what I would have taken. The journalism course was all about news gathering and writing for old-fashioned newspapers. I wanted to write about rock for the NME or Creem or failing that, Rip It Up. So I approached Murray Cammick early ’79 and an appointment was made for me to meet up with co-founder Alastair Dougal in a Wellington coffee shop. It was a weird meeting. I was still painfully shy – too much so to tell him what I wanted to write about – and he blathered on about artists I had no interest in, like the old-fashioned rock’n’soul of Graham Parker.

I did, however, walk out of there with a commission: to be Rip It Up’s Wellington correspondent, writing a monthly what’s on column called Rumours, the occasional record review and the odd feature. In September I wrote the lion’s share of a Wellington supplement that featured a report on Marmalade Studios and a piece on a group called Short Story, whose story turned out to be short indeed. I was offered the princely sum of $60 but Murray hand-delivered a copy of a Clash EP instead. I hated it.

That same month, my bosses at The Evening Post – where I was a junior subeditor – asked if I’d like to be their music writer. I would be taking over from Hannah Wallis (now a long-time reporter for Fair Go) and Cameron Bennett (later a current affairs personality) and their expectation was that I would work for free outside of my 7.30 to 2.30 shift, just when everyone else took off to get shitfaced in the pub downstairs. The opportunity to write about rock for a captive audience thrilled me to the bone, and I spent the rest of the year (and some years into the future) churning out weekly album review columns with my ugly mug pictured on the page, which made me something of a recognisable figure in that very compact city.

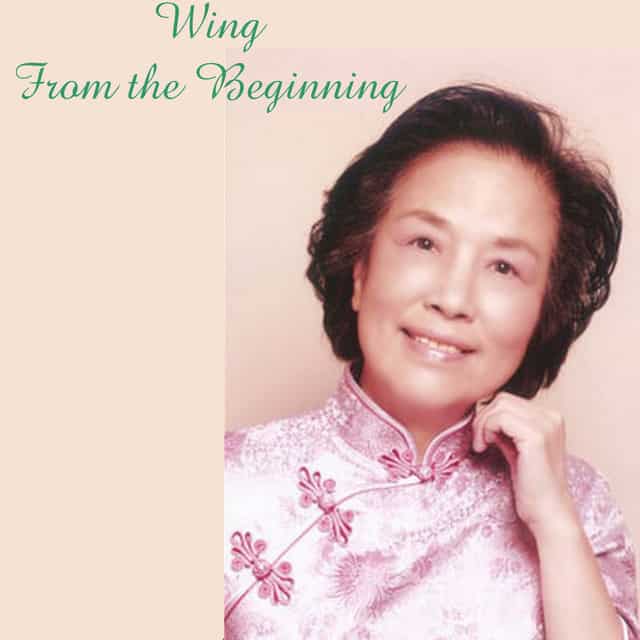

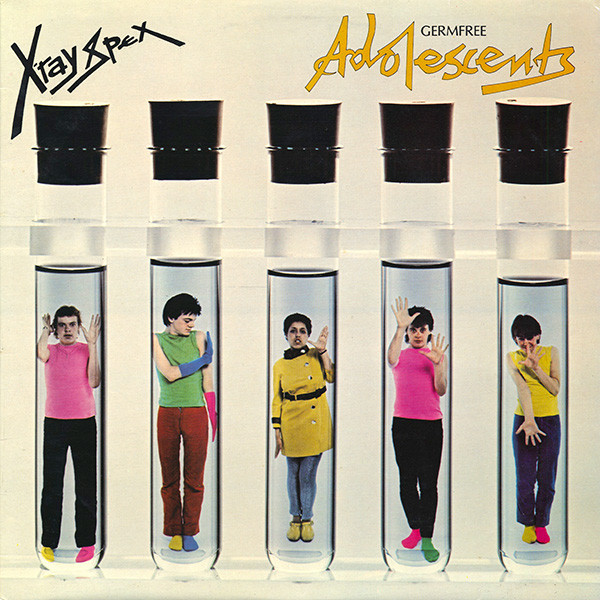

From that point on I got overwhelmed with record company freebies. Boxes of vinyl would turn up every day and at one point it seemed like I was getting 20 to 30 new albums to review each week. I was very diligent and listened to everything, even though most of it was litter-box scrapings, but in truth, I did find a few good things in the four months of ’79 remaining, including X-Ray Specs’ Germ Free Adolescents (released in the UK in ’78 but in those days us Kiwis down in the colonies had to wait up to a year for ‘new’ records), The Undertones’ self-titled debut, Frank Zappa’s Joe’s Garage, and XTC’s aforementioned Drums & Wires.

It’s still a bit sad, though, that my favourite year in music of all time (if I don’t count my other favourite years from ’66 through ’73) saw me naively struggling to get up to speed and missing out on reviewing most of the great stuff.

It’s still a bit sad, though, that my favourite year in music of all time (if I don’t count my other favourite years from ’66 through ’73) saw me naively struggling to get up to speed and missing out on reviewing most of the great stuff.

I’d been a great advocate of punk from the time of Dylan Taite’s UK expose in ’77, and had soaked up all the propaganda – loving the attitude – but was unconvinced by much of the music itself. Apart from Johnny Rotten’s utterly unique singing style The Sex Pistols just sounded like rock and roll and The Clash were even more trad. When I visited Wellington in late ’77 to apply in person for the journalism course, the first thing I did was to hightail it up to Colin Morris Records on The Terrace, where I purchased my first Pere Ubu record and heard what I thought ‘punk’ should sound like. Post-punk had all the edge of punk but also a restless creativity that I adored, but my personal tastes always veered more towards the experimental than they did the pop end of the spectrum. Bands like PiL and This Heat and Chrome were doing new things with sounds and talking it all up in a radical way, which suited the apocalyptic feeling of the times.

I didn’t look the part, though, and I stubbornly kept my long blonde locks and flares until sometime in 1980 when I finally bowed to fashion and got a short cut and drainpipes. Silly me, I’d taken John Lydon at his word that you didn’t have to dress like a punk to be a punk, and I loved the fact that Mark Smith of The Fall looked just like any young geezer you might meet down the pub. But I wanted to meet girls, too, and I didn’t want to look like a Genesis fan or anything, so off came the locks.

I was a bit slow to pick up on the local scene, as well, which had been fermenting away for about a year when I finally ventured into Willy’s Wine Bar on the corner of Manners Mall to hear a very interesting band called The Spies. And the fact that I was now writing about bands somehow gave me the courage to start going to more small local gigs that year, including quite a few at The Last Resort, which was still in its infancy and was more of a hippy pad with bean bags on the floor and carrot cake at the counter. Run by bassist Clinton Brown, it featured bands like The Crocodiles and long-haired rock scribe Mike Alexander was often there propping up the non-alcoholic counter.

It was in 1980 that I suddenly became infatuated with the Wellington Terrace scene bands, and especially Shoes This High and a couple of groups from out of town: The Features, and The Gordons. But none of that belongs here because we’re talking about 1979.

Like most events in my life, ending up writing about music was something of a lucky accident, or perhaps a simple twist of fate. I was so meek back then and terribly introverted that I would never have actually asked for the job. Forty years on, sometimes I wish I had taken a different road in life, and maybe even accepted that job offer as a fresh-out-of-school junior librarian in Hamilton, but back in ’79 writing about rock was literally everything I wanted to do in life.