Electricity prices have soared 80 per cent since the sector was amalgamated, corporatised and privatised 30 years ago. Alasdair Thompson explores whether that is reasonable.

The last review of electricity pricing was 10 years ago. It was launched by then minister of Energy, Gerry Brownlie, after National came to power in 2008 and followed eight years of high residential power price increases, the accumulated impact of which was a whopping 78 percent.

The last review of electricity pricing was 10 years ago. It was launched by then minister of Energy, Gerry Brownlie, after National came to power in 2008 and followed eight years of high residential power price increases, the accumulated impact of which was a whopping 78 percent.

Since then price rises have been more moderate. Nevertheless the new minister, Labour’s Megan Woods, announced another review earlier this year. Its initial findings came out this week.

Brownlie clearly had good reason to launch his review back in 2008. There is not the same imperative for this latest review as increases in the past decade have been in line with low inflation.

Nevertheless, Woods wanted to take another look at whether the 80 percent increase in residential power prices over the last 30 years is reasonable or not.

The new report found that 103,000 households spend more than 10 percent of their income on electricity. These people are said to be struggling to pay for power and are going without it, suffering the ill health impact of cold damp houses.

The new report found that 103,000 households spend more than 10 percent of their income on electricity. These people are said to be struggling to pay for power and are going without it, suffering the ill health impact of cold damp houses.

This situation probably has as much or even more to do with low incomes in New Zealand than it has to do with particularly high power prices.

There is also concern about fairness and transparency of pricing. One has to search out the cheapest price among the confusing plans of 44 suppliers.

Furthermore there is anecdotal evidence that because low income households can’t pay their power bill when it is due they miss out on the very substantial discounts some companies offer for paying on time – turning the discounts into penalties – which means the poorest pay a lot more.

So, have residential electricity price increases been reasonable or not? The answer depends on which periods of time you look at over the past 30 years. But whether you take the period since 2000 or since 1988 until now, price increases have averaged about 2.1 percent pa and less over the past 10 years.

So, have residential electricity price increases been reasonable or not? The answer depends on which periods of time you look at over the past 30 years. But whether you take the period since 2000 or since 1988 until now, price increases have averaged about 2.1 percent pa and less over the past 10 years.

Many other things have inflated in price much more than electricity in those periods. Among the worst have been council rates and charges.

Brownlie’s review led to a package of reforms aimed at enhancing competition and a big promotional push to get people to shop around for the best pricing deals. Those that did so benefitted. I know – I have changed suppliers five times since 1998.

This last year alone 22 percent of households changed their supplier to get a lower price. The better informed and more proactive people do this. And they have reduced their electricity costs.

This last year alone 22 percent of households changed their supplier to get a lower price. The better informed and more proactive people do this. And they have reduced their electricity costs.

CPI inflation over the past 10 years was 18.94 percent and residential power bills rose about the same amount, that is 1.6 percent pa. Not too bad.

So what’s the point of this latest review? It’s not absolutely clear. Maybe it’s just what new energy ministers do?

To be fair though, electricity company profits reported during the current reporting season have mainly been high, and the world of energy is changing.

For example, private solar power and storage batteries are reducing some consumer’s dependence or need for traditional electricity supply. But we still have the entire built infrastructure to deliver us the traditional electricity. If increasing numbers don’t use that infrastructure, will the rest who do have to pay more for it?

For example, private solar power and storage batteries are reducing some consumer’s dependence or need for traditional electricity supply. But we still have the entire built infrastructure to deliver us the traditional electricity. If increasing numbers don’t use that infrastructure, will the rest who do have to pay more for it?

On the other hand, electric vehicles (EVs) are increasing in number. Many recharge their batteries from mains power.

Slow trickle charging one EV from the grid is equal to connecting one extra house, all the way up to twenty extra houses, if the most rapid charging is used. The Greens are supportive of subsidising this cost to encourage more EVs.

How much may that increase demand or electricity from the grid in the next 20 years? Will that lead to more expensive investment in a generation? Upon whom will the costs of a huge increase in EV demand really fall if its users are subsidised?

How much may that increase demand or electricity from the grid in the next 20 years? Will that lead to more expensive investment in a generation? Upon whom will the costs of a huge increase in EV demand really fall if its users are subsidised?

So this pricing review hopefully goes beyond what you and I currently pay for our electricity. In fact, there is no guarantee we will pay less as a consequence of it. For example, it may identify the need to increase generation and distribution capacity to supply power to EVs.

Increased investment has to be paid for.

Then again, it may see ways to increase the efficiency of the industry. Do we need 29 electricity distribution companies? Is the wholesale market sufficiently transparent and competitive? It should be after all these years of Electricity Authority regulation, but who can say for sure?

Then again, it may see ways to increase the efficiency of the industry. Do we need 29 electricity distribution companies? Is the wholesale market sufficiently transparent and competitive? It should be after all these years of Electricity Authority regulation, but who can say for sure?

While profits do not tell us if we are being ripped off by our electricity supplier, they do tell us how well they and their shareholders are doing, and in the main, the answer is ‘pretty well’.

There are 44 electricity supply companies. The four biggest are Genesis, Meridian, Mercury and Trustpower.

In their last annual reports Genesis’ Earnings before Interest, Depreciation, Tax, Amortisation and Fair Value adjustments (EBITDAF) were up eight percent to $360.5 million. Meridian’s was flat at $201 million. Mercury was up seven percent at $561m. Contact was down six percent at $494 million and Trustpower was up 22 percent at $267 million.

That is $1.884 billion profit last year between just these four.

Quite apart from the 15 percent GST in the price consumers pay, the government also gets a whole lot of income tax too from these electricity companies including generators, the national grid, and the lines companies.

Before the electricity reforms in 1997 these electricity lines and supply companies were not for profit power boards. They paid no income tax. The grid and the generators were state owned. They made profits but often insufficient enough to fund their investment for growth. What’s more the lines and supply companies charged higher prices to commercial customers to subsidise their residential customers who elected their board members!

After the reforms in the late 1990s, cross subsidising residential customers by charging higher rates to business was no longer allowed.

In fact, big manufacturers and mills could all now buy electricity on much cheaper contract prices or even cheaper still via the wholesale spot electricity market.

In fact, big manufacturers and mills could all now buy electricity on much cheaper contract prices or even cheaper still via the wholesale spot electricity market.

This is an important point. The lowering of commercial power prices meant residential power prices went up. It was a rebalancing of prices between commercial and residential consumers, not necessarily an overall increase in prices.

Power companies were now expected to make a profit and pay dividends and income taxes. They have. They have made big profits and paid billions of dollars in taxes too, since 1998. Taxes someone else (you and me) would have had to pay, had the government not enjoyed this boost to their coffers.

So while residential prices have gone up a lot since 1998 there have been benefits too.

After the rebalancing of residential and commercial prices had been completed, increases have been lower than, or in line with, inflation.

Electricity industry profits increased hugely, largely due to efficiency gains and the whole country has benefitted from the massive taxes and the dividends power companies now pay compared to their forerunners who paid no taxes and no dividends. Neither has the government had to find capital to expand generation. The companies do that.

Electricity industry profits increased hugely, largely due to efficiency gains and the whole country has benefitted from the massive taxes and the dividends power companies now pay compared to their forerunners who paid no taxes and no dividends. Neither has the government had to find capital to expand generation. The companies do that.

Yet it is disconcerting that New Zealand’s power prices are well above the OECD average. It is also noteworthy that the New Zealand Energy sector is among the most highly paid.

Among the OECD countries, Norway (99 percent hydro power) has the cheapest electricity and Greece has the most expensive. The average cost of electricity in the OECD in 2016, after taking account of purchasing power parity, is US$179.50 MWh. New Zealand’s cost was US$197.10, or 9.8 percent above the average.

That is too high, especially given that 80 percent of our electricity comes from renewable fuel hydro, geothermal and wind power. The ‘fuel’ is free. Costs are limited to the cost of the capital involved in its harnessing and distribution. Our mostly small scale gas generation plants are also efficient and more expensive is only used sometimes at Huntly.

However, distribution via the national grid and 29 local lines companies to a relatively small population is challenging and costly on a per customer basis.

The drive to gain efficiencies and lower power prices must never cease. It is not only important to the 32 percent of users who are residential users, it is just as important to commercial, industrial and farming users, many of whom compete on international markets.

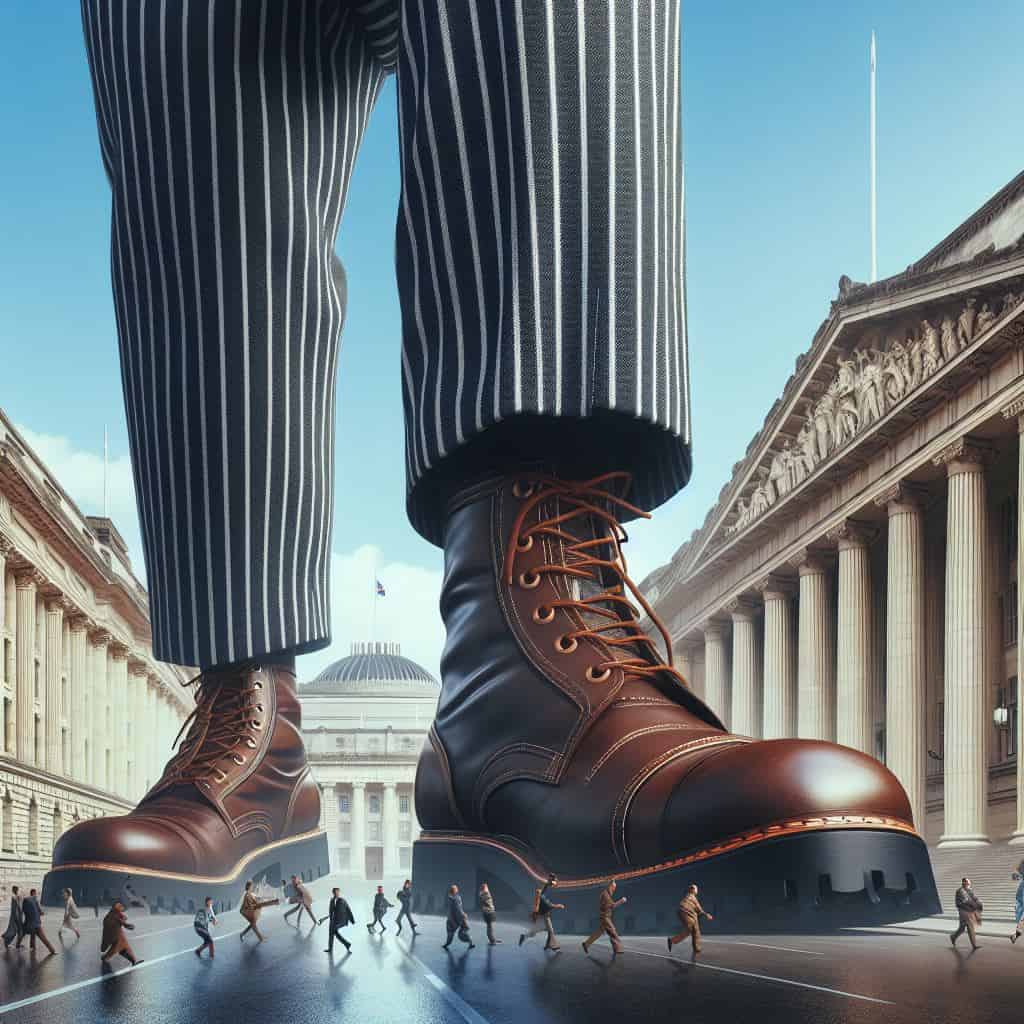

Revolting man who belongs in the past.