America is suddenly examining its deep, worrying underbelly of racism through its cinema, writes TOBY WOOLLASTON.

Has 2017 signaled a shift in whose stories are being told in the cinema?

Has 2017 signaled a shift in whose stories are being told in the cinema?

Having just attended a media screener for Kathryn Bigelow’s latest film, Detroit, a film about a group of black youths in the 1967 race riots, it struck me that perhaps the cinematic world is beginning to grow up, resulting in a minor groundswell of films which are telling the stories of ‘ethnic minorities’. Perhaps it’s a temporary blip, but a welcome blip nonetheless.

So, who is telling these stories? Some argue that the power brokers are history’s writers. And as the argument goes, Kathryn Bigelow (a white American) has no right to tell the stories of black people. Certainly Pulitzer Prize winner August Wilson subscribes to this point of view. His play, Fences, is about a disgruntled father carrying the baggage of his neglected upbringing, and bitterness over missing a shot at big-time baseball due to the racist selection policy of the 1950s. Denzel Washington posthumously helmed his adaptation for the big screen. Wilson, who died in 2005, insisted that an African-American direct the film version of his play.

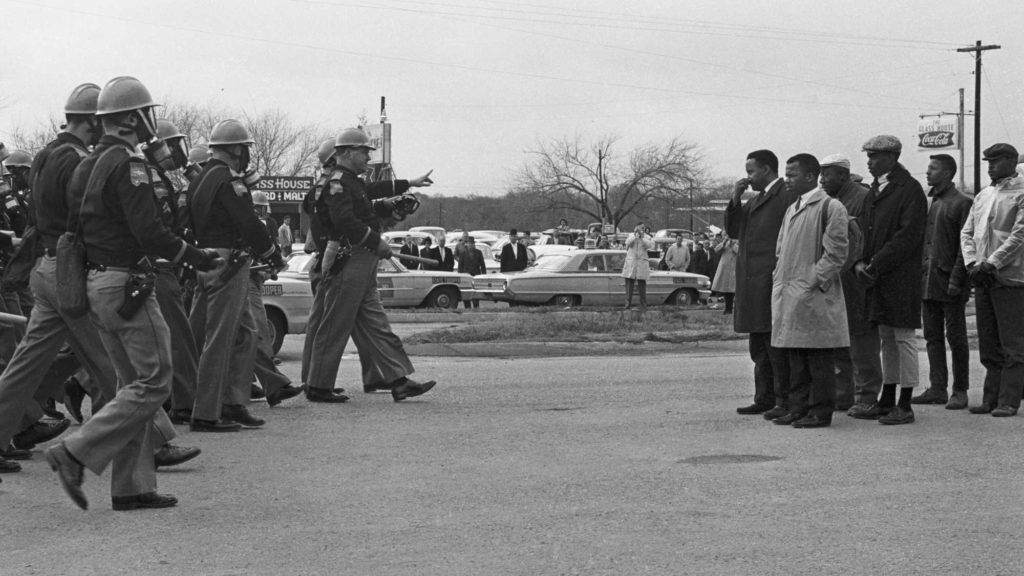

Raoul Peck’s documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, is in lockstep with Fences. This film unapologetically meets America’s racist past head-on. “The future of the negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country” – This provocative statement from the film by black activist James Baldwin may on the surface sound reductive but his stance is unflinching and he unapologetically uses black lives as the benchmark of America’s success as a nation… and in Baldwin’s words, “it is not a pretty story.” In 1979, Baldwin penned the beginnings of a manuscript that was to be his next project, called Remember This House. Haitian born director Raoul Peck took these pages and created a documentary that is a stimulating rendition of Baldwin’s seminal work.

I Am Not Your Negro and Fences are important films, not just as a document of America’s checkered racial history but also as a warning to the world about the fragility of racial difference. They shrewdly illustrate the historical treatment of America’s black community in order to access deeper fundamental problems within America, and indeed Western civilisation. Just as Al Gore has used climate change to illustrate our problems with materialism, similarly James Baldwin and August Wilson use a racist America to illustrate our seeming fundamental inability as human beings to embrace ethnic difference and commonality. Baldwin posits: “It’s not a question of what happens to the negro here, to the black man here… but the real question is what’s going to happen with this country.” He argues that America’s problems that created “the nigger” still exist today and is a “formula for a nation or kingdom decline”. With a finger firmly pointed at Western civilisation (although it is difficult to think of any civilisation, past or present, where cultural difference has been harmoniously embraced) the film at its core seems to wrestle with the age-old conundrum of humanity’s inability to grasp power.

Both Fences and I Am Not Your Negro (Roschdy Zem’s Chocolat being another) are fine examples of black activism, as penned by their own people, spreading its wings on the silver screen. But is there room for ethnic minority stories to be told by people from a different ethnic background?

There have been some affective examples this year – such as the aforementioned Kathryn Bigelow-directed Detroit. Set to the backdrop of the Detroit race riots, the film begins by explaining that the pointy end of the maligned racist stick is the result of historically deep-seated problems. Certainly, Detroit and I Am Not Your Negro would make the perfect double bill. However, despite Detroit’s good intentions, it just does not have the unbridled confidence to ascribe fault with white power that I Am Not Your Negro does, and rightly or wrongly steps back from this responsibility. The film paints a black community in utter fear of a predominantly white police force, although it stops short of being a complete diatribe against white authority – its main antagonist, Krauss (Will Poulter), portrayed as an unhinged policeman drunk on power rather than being representative of white motivations.

Similarly, Wind River, directed by Taylor Sheridan, also dances its way around the treatment of Native Americans. It is a perfectly serviceable thriller in its own right, but its racial ideals fall well short of a film’s responsibility to go beyond the call of mere entertainment when dealing with sensitive topics such as race and gender. The film clearly renders a story fit for white consumption with its protagonist, Lambert (Jeremy Renner), becoming the great white saviour, applying the mop to an impotent cultural minority unable to deal with their own problems.

On the other hand, Jeff Nichols’ Loving is a good example of a story that champions black agency, despite opportunities to do otherwise. Set in 1958, prior to America’s civil rights revolution, Loving is based on a true story about an unlawful interracial marriage between white-American Richard Loving (Joel Edgerton), and African-American Mildred Jeter (Ruth Negga) in Washington DC, where interracial marriages were legal. However, on their return home to Virginia where interracial marriages were not permitted, they were met with legal roadblocks as the state saw to throw them out under threat of imprisonment. Years of legal and social tumult saw their case taken all the way to the Supreme Court, where the couple’s relationship finally prompted the overturning of those laws nationwide.

Loving is a film that is surprisingly non-belligerent in tone, despite the outrageous injustice of its subject matter. Instead, it calmly states its case and proceeds to leave the histrionics to the viewer. It is a slow burn that is satisfyingly sure of itself. What is remarkable is the bold move to not only explore the boundaries of racial segregation but also comment on gender politics. Typically, the husband is seen as the enduring pillar of strength, fighting the good fight, while the wife plays a passively supportive role. Here, it is increasingly apparent that the real hero of Loving is Mildred as she begins to take control of their situation. Nichols masterfully presents this visually, as Mildred becomes more and more centred in the film’s frame and Edgerton is gently ushered to the margins. The diminutive Negga returns the favour by giving a wonderfully authentic performance that no doubt draws from her own experience as a child of mixed race (being of Ethiopian and Irish descent).

So, it seems this year has thrown up a mixed bag of films about America’s dubious racial history, but at least their stories are being told. 2017 has also allowed us to compare retrospective examinations with current stories. Standout films such as Get Out and Moonlight take a more introspective approach and highlight that America hasn’t exactly become a beacon of racial tolerance.

Jordan Peele’s film, Get Out, has delivered a scathing social critique that is dressed up as a horror film. It’s nothing new for the horror genre to be a vehicle for social commentary – Zombies as a metaphor for consumerism, misogyny equating to a pathological fear of feminism, yada yada yada. However, it is rare for horror to comment so vehemently on race, as is the case in Get Out. It’s a subtext that the film wears proudly on it sleeve for all to see. In fact, it’s barely a subtext at all because it’s so assertive about racism that it makes American History X feel like a film about cheese making. Forget about your clichéd southern hillbilly racism, this is the benevolent but sinister brand of racism that is firmly ensconced in the underbelly of liberal America.

Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, however, dials thing back. The film is presented in three acts spanning the formative years of Chiron, an African-American, from childhood through adolescence to adulthood. Growing up in a rough neighbourhood, his journey of self-discovery deals with universal themes of identity, sexuality, family, and most of all, masculinity. He discovers from an early age that certain feelings have no place in the hostile environment he lives in, and finds himself constantly on the outer. Chiron struggles to come to terms with his sexuality and his place in the world, all the while managing his drug-addled mother (played by Naomie Harris). Indeed, Moonlight is a story about being black in America but is also a heartfelt examination of what it is like being black and gay.

As such, Moonlight signals an appropriate juncture to change tack. My next article will examine some of the notable films of 2017 through the context of gender and sexuality.