Why radio, in all its manifestations, and for all its potential, will probably always suck. By Gary Steel

IN 2005 I made a startling discovery. It was a completely new kind of radio station, called Pandora. From my mouldering rental North Shore hovel, via the wonders of the world wide web, with a lot of buffering I could, spasmodically at least, listen to an American radio model that appeared to have built-in adventure.

IN 2005 I made a startling discovery. It was a completely new kind of radio station, called Pandora. From my mouldering rental North Shore hovel, via the wonders of the world wide web, with a lot of buffering I could, spasmodically at least, listen to an American radio model that appeared to have built-in adventure.

My beef with commercial radio – apart from the interminable crap jizzed over the airwaves by egomaniacal, narcissistic jocks – has been its essential problem. By its very nature, radio is there to serve the advertisers, so the one aim, invariably and monotonously, is to serve up the best ratings. This translates to one harsh imperative: the music played must get enough bums on seats, and the right bums on seats, to appease the sponsors. From there, it’s all downhill.

What this means for listeners is that things get very safe, and very predictable, very fast. They might say: but we only give ‘em what they want! To which I say: if you give ‘em what they (think) they want, they’ll want what they get, so they’ll get what they want, over and over for all eternity. But the thing is, real life isn’t like that. Even the most conservative music fans get bored with the same old playlists, and yearn for something to stimulate and challenge them, even if it’s just a little bit. Or at least, I would hope so.

And the reason Pandora was such a blast? Well, it’s founder, a struggling musician who goes by the name Tim Westergren, and a small team of likeminded souls, had come up with a new formula, which they named the Music Genome Project. What it meant for the listener was a selection that always contained some of the characteristics of the music you liked most, but didn’t necessarily sound like that music. For instance, if you chose a station called ‘Tom Waits’, it would occasionally play a song by the bohemian growler, but the rest of the selections weren’t just Waits’ copyists or singer-songwriters with drunk-sounding vocals or junkyard instrumentalists. The Music Genome Project had focused on certain textures, or rhythms, or sounds, and chosen its selections using the information that had been carefully researched.

Pandora was vastly more entertaining and unpredictable to listen to than other internet radio stations, unless you were on a monomaniacal journey to experience a whole slab of ‘70s roots dub or Celtic whimsy, or whatever. But my love affair with the station ended one day when I got a message saying that, because of international copyright laws, it would no longer be available in my territory. I had never thought of New Zealand as being a territory, because I don’t have a territorial bone in my body, but I knew what it meant: it meant that those copyright bastards had snuffed out a perfectly great way to enjoyably waste hours of my time.

Pandora was vastly more entertaining and unpredictable to listen to than other internet radio stations, unless you were on a monomaniacal journey to experience a whole slab of ‘70s roots dub or Celtic whimsy, or whatever. But my love affair with the station ended one day when I got a message saying that, because of international copyright laws, it would no longer be available in my territory. I had never thought of New Zealand as being a territory, because I don’t have a territorial bone in my body, but I knew what it meant: it meant that those copyright bastards had snuffed out a perfectly great way to enjoyably waste hours of my time.

So, when Pandora reappeared here in 2012, I was fairly excited. In the meantime, a bunch of would-be usurpers of Pandora’s mojo had turned up on our doorstep, including Dutch wannabes Spotify, whose presence here dwarfs that of its older cousin. But here’s the rub (one of them, anyway): Spotify is geared towards creating personal playlists, which right from the get-go, suggests that it’s more an exercise in nostalgia for many of its listeners than a medium through which they might want to explore and find new acts, songs or albums. Pandora, on the other hand, doesn’t allow playlists or searching or repeating of certain songs. What it has added to its arsenal, seemingly to make it more user-friendly for listeners, is the ability to give a thumbs up, or thumbs down, on each selection that comes up. Since Pandora has been back online in NZ, I’ve discovered to my dismay that the results I’m getting to various ‘stations’ (read: artists) are disappointing, predictable, safe and boring.

For instance, if I choose ‘Jimi Hendrix’, I’m likely to get a very generalised ‘Classic Hits Of The Psychedelic ‘60s’ rather than something that cleverly picks out the intrinsic properties of the genius guitar-slinger’s music and finds other music that shares some of those properties.

I couldn’t work out why this was happening, when Pandora had put so much effort into its Music Genome Project. The results I was getting were only marginally more refined than some of the music matching services that have been around for some years.

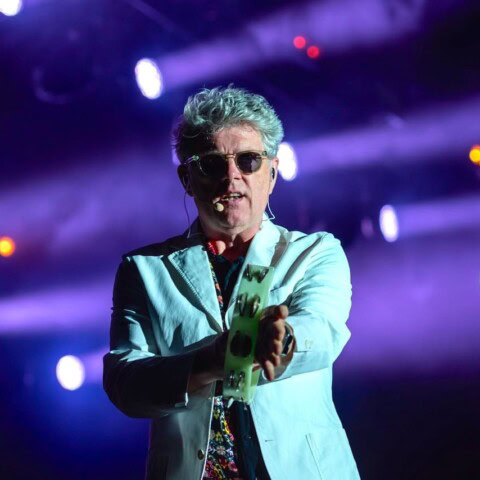

I was soon to get my answer to this pressing question/dilemma. A couple of months back, I was invited to a meet and greet and evening speech by the founder of Pandora, Tim Westergren. The local Pandora representatives had cleverly mined interested members of the local Pandora listenership, hundreds of which turned up to hear this radio guru talk about the back-story of the company, and its plans for the future.

Before the event, I was introduced to Tim as a long-time listener/fan. I saw my chance to ask the hard question, so I took it. He explained that the reason I wasn’t getting the complex and interesting results from ‘Jimi Hendrix’ (or even ‘Tom Waits’) anymore was due to the power of the people: sadly, with every click on the ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ button, the results are influenced across the board. What this is, in effect, is the dumbed-down effects of democracy: the vast majority of people who listen to Jimi Hendrix want to hear songs from that era, rather than explore songs from other eras that share certain aspects of Hendrix, or songs of a different style to Hendrix that nevertheless, share some characteristics. He sounded rather defeated to have to admit to this; that a great swag of conservatively-minded listeners could influence this beautifully and carefully rendered thing called the Music Genome Project with their desire for nothing more than nostalgia on steroids.

Before the event, I was introduced to Tim as a long-time listener/fan. I saw my chance to ask the hard question, so I took it. He explained that the reason I wasn’t getting the complex and interesting results from ‘Jimi Hendrix’ (or even ‘Tom Waits’) anymore was due to the power of the people: sadly, with every click on the ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ button, the results are influenced across the board. What this is, in effect, is the dumbed-down effects of democracy: the vast majority of people who listen to Jimi Hendrix want to hear songs from that era, rather than explore songs from other eras that share certain aspects of Hendrix, or songs of a different style to Hendrix that nevertheless, share some characteristics. He sounded rather defeated to have to admit to this; that a great swag of conservatively-minded listeners could influence this beautifully and carefully rendered thing called the Music Genome Project with their desire for nothing more than nostalgia on steroids.

In essence, this means that Pandora has unwittingly become just like any other radio station, except that instead of pandering to advertisers, it’s pandering to the nostalgic impulses of the majority of its listeners. Sure, it doesn’t have the babbling DJs or the incessant advertising. Result? Same thing.

NZ Pandora rep Chris Henry later makes a point in replying to one of my Tweets with this: “One of the main selling points of Pandora is the effortless delivery of music based on a single artist or song.” And that’s fair enough, fine and dandy. Still, I don’t really get it. If that effortless delivery is going to dish out stale, predictable fare based on a single artist or song, is it really doing anything worthwhile, apart from keying into that base human craving for the familiar?

Still, I thought I’d stick around and hear what Westergren had to say. I mean, it’s always interesting to hear some guy who looks like Mr Emo but who is actually the bright cookie that jump-started a whole new type of radio, even if it has rather regressed from its raison d’etre.

Westergren said that his original aim was “to be Oscar Peterson”, and he did perform in a number of bands, but like most musicians who end up not making a living doing what they love, before long he was doing whatever it took to survive: in his case, nannying!

His idea was to create a recommendation tool for the internet, and in 2000 he mustered $1.5 million of investment to research the business.

The way that the Music Genome Project works is that every element of a song is broken down by a bunch of musicians to see what makes its component parts, it’s musical DNA. This takes more than an hour for a classical piece, less so for a 3 minute pop symphony!

Their very first test of the calculation/algorhythm was a Beatles song, and the band it came up with was that “Beatles knock-off band the Bee Gees… before they were a disco band.”

[Okay, because Westergren is clearly too young to have been around in the ‘60s/’70s, I guess we can forgive him for his chronic lack of understanding about the Bee Gees – the iconic status of their early work and the fact that, far from being a Beatles knock-off, they existed at a time when the Beatles practically were the pop universe, with everything else revolving around them.]

Anyway, the 50 people working at Pandora had to accept a deferral of their wages by 2001 when the funding had all run out, and they soldiered on for two whole years on no pay!

“If it didn’t work out I was going to Mexico,” said Westergren. “I was so deeply in debt.”

Then, he managed to raise nine million dollars in finance, and was able to provide two years worth of back pay to staff.

He says they had analysed an enormous collection of music by Pandora’s launch in Autumn 2005, and since then, despite not having been hugely profitable, it has amassed over a quarter billion registered users.

“Our ambition is to be a huge part of radio”, admits Westergren, who doesn’t really tell us anything when he says that we’re being served poorly by conventional radio. His thing, as you might expect, is all about portable gadgets, smartphones and even cars: “Don’t buy a car without Pandora as an embedded app”, he says.

When someone asks about competition from the other players, he maintains that Pandora is ahead of the game, and that “personalised radio is difficult to do well. There’s two things we do – the music genome, and the thumbs, which change the selections.”

When asked about the controversial issue of payments to artists, he admits that it’s something that hasn’t yet been resolved.

“The per song amount is very low,” he says, “a fraction of a penny, but last year we paid 60 percent of our revenue.” It’s a very complex issue, with the collection agencies playing an important role, but he points out that in the US, artists don’t get anything at all from broadcast radio.

Pandora is “a fantastically powerful medium for artists”, and to that end, they’ve taken on a strategy for getting independent artists on the station. His hope is that some of these artists will be able to establish a fan base and a career based on their profile through Pandora.

He seemed like a genuinely genial but driven chap, but I couldn’t help wondering whether, in the long-term, audiences would favour the Pandora approach over the ability some services offer to select certain songs or albums and create playlists. As a music reviewer, I’ve certainly found Spotify more useful than Pandora, because I can easily check out a new song or album or artist.

He seemed like a genuinely genial but driven chap, but I couldn’t help wondering whether, in the long-term, audiences would favour the Pandora approach over the ability some services offer to select certain songs or albums and create playlists. As a music reviewer, I’ve certainly found Spotify more useful than Pandora, because I can easily check out a new song or album or artist.

And then there’s that issue of listener dumbing-down of the Music Genome Project. They’re got to address that if they don’t want it to be just like everything else. The problem to a large extent is us: whenever we cluster together in large numbers, we take the path of least resistance, without thinking how cool it would be to try something new. It’s about comfort, but being comfortable isn’t necessarily the best state to be in: people are ‘comfortable’ with John Key’s smiling face while his government continues to mock the power of the people. Being comfy often brings with it really bad results.

I wish Tim Westergren and his Pandora the very best. It certainly started out with a novel concept; and who knows, maybe they’ll get back there, or at least figure out some setting for those who are desirous for a bit of musical adventure. GARY STEEL