The idea? Every day in May, to mark NZ Music Month and the new AudioCulture archive, Gary Steel would present something local from his considerable behind. Personal archive, that is. Except that mysteriously, it didn’t quite happen every day. There were only 29 entries for a 31-day month. So belatedly, the old tardy bastard will in the next two days – whether you like it or not – provide another two pieces. Today’s grand finale?

Requiem For Wellington Rock

First published in the Wellington City magazine, 1986 (possibly June).

For the next few weeks

I kept haunting the bars

Just looking for a place to play.

Well, I thought my pickin’

Would set ‘em on fire,

But nobody wanted to hire

A guitar man.

DUANE EDDY

Music is IMPORTANT. Pop and rock define the feeling of a blooming youth generation set to ignite after the cold war vibes of the ‘50s. Serious electric rock music is a human/spiritual sky projectile ready to explode on the edge of earth’s atmosphere. The Monkees are another reality; a version of the same dream for pre-pubescents viewed through junk culture medium television, and its enemy moguls. We were youth, incorruptible. We wanted the world and we wanted it NOW.

Music made in Wellington topped the pop charts.

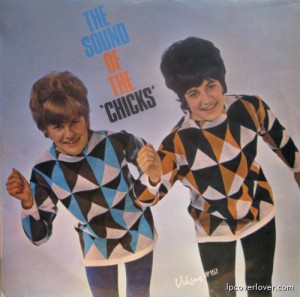

Between 1966, when the charts were inaugurated, and 1972, local music was adored as avidly as its overseas ally. Our own idols had massive followings. Mr Lee Grant and Craig Scott were mobbed in the street. The centre of the NZ recording and music scene was in Wellington, and New Zealand music ruled.

What the hell happened? Over the past 10 years Wellington music has languished in a neglected nadir. Was NZ music better in the ‘60s?

Looking Back At A Golden Age

Says Hayman: “Australian and New Zealand groups started doing covers of all these things. We used to turn out albums that had covers of everything on the charts in the States.

“They used to give you half a day to do a whole album, and you’d go in with three bands and mix up guys – the drummer out of one, the brass player out of another.

“You just had to do these things with whoever you had available. They were pretty rough, the beginning of K-Tel records, actually. It used to take three-and-a-half hours to do an album and it was done on a four-track tape recorder, so there’s no overdubbing. Close enough’s good enough!”

Using his own band, Hayman turned out an astonishing tally of 15 albums and 20 singles.

Whether it was this bargain bin principle which indeed spurred support for New Zealand pop is ultimately irrelevant. NZ television pop paraded a succession of bimbos whose starts burnt bright in the prevalent climate. NZ radio was on the case. Support was there. There was an optimism in the ‘60s, borne out of “more affluent times… life was pretty easy”, says current record company owner Jim Moss.

Rick White, ex-leader of blues band Tom Thumb, reckons that the success of local bands in the ‘60s was tied in with an audience naivety. Not that the bands were bad, just that musicians and audience alike were seeing things without the skepticism we view Next Big Things in 1986.

Redmer Yska, long-time Wellington music observer and journalist, paints his picture of the late ‘60s:

“There were three sorts of clubs. Sophisto-sleeze joints like Downtown that would really rock. Then there were the folk clubs… candles and coffee and chocolate cake and polo necks and beards.

“There were three significant folk clubs: Mone Marie where the Rinascimento in Roxburgh St is… a varsity beatnik place, Chez Paree in Majoribanks St which was very popular, and the Balladeer in Willis St.

“The other sort of clubs were rock clubs. The Place – later the Montmartre – was in Chews Lane, and had red lights, formica tables and lots of Coke. Bands like the Pleasers and the Kal-Q-Lated Risk played there.”

Blues was the big thing for musos on the alternative scene, and the hippest bands would quite happily spend their time emulating their British blues stars like Eric Clapton and John Mayall.

Tom Thumb never cracked the national charts but had a number of regional hits.

Just as now, there were factions and to pre-hippy audiences, clothes were of stringent importance, says Yska: “There were two real kingbee shops. His Lordships, which is still going, and The Vault, next to Vance Vivians.

“Over the road from The Vault was the best gig in town, reflecting the coming interest in psychedelia: The Mystic. That changed its name to the Oracle. They really took the temperature of the zeitgeist. There was also The Psychedelic Id in Majoribanks St. People would go along in girl guide uniforms, military outfits. The Joyful Cry played there. They were Reno, Paddy and Ben, had giant afros and played straight Hendrix.

“They were quite innocent days and we were dedicated followers of fashion.

“The Musicians Club was also active. Geoff Murphy (of BLERTA and Goodbye Pork Pie, among other things) used to play trumpet and Bruno Lawrence drums. Bruno was in a band called The Claude Papesch Trio. They released a single called ‘Bruno Do That Thing’ in ’65-’66.

“People were shaking off the utter austerity of the ‘50s. It was a transitional time, and New Zealand was coming alive.”

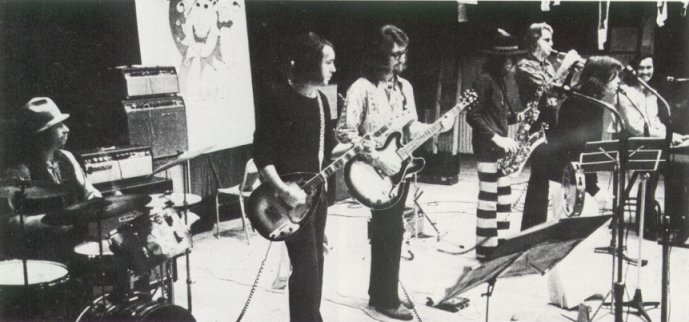

For the Quincy Conserve the ‘60s were an exciting and fruitful time. In 1967 Malcolm Hayman returned from a decade working in Australia and Europe. Quincy Conserve benefitted from Hayman’s firm direction and arrangemental ability – they were a funky jazz rock band – and included some of the best musos around… ex-Quincy musicians are sprinkled around the world now, the most famous being drummer Richard Burgess (who headed his own techno band Landscape in England, and produced the recent number one Pet Shop Boys hit) and Bruno Lawrence (who needs no further ado).

“I can remember cutting a track called ‘Maria’ with him. We had half the National Orchestra in the studio and he had to put the voice down. We were there from 9am in the morning to 4.30 in the afternoon, and he still didn’t get it down. He couldn’t sing in tune. These string players were worn out… they couldn’t even vibrato in the end. We were stopping for numerous cups of coffee and swearing sessions in the toilet. But he was a good act. He used to have the suits ripped off at the arms… it was all set up, he would have these girls run up onstage, grab the suit and tear at him.”

Mr Lee Grant’s manageress would “go round every record shop in Wellington and buy every copy, and then recirculate them.”

But the biggest secret scandal was with one hit wonders Creation in the early ‘70s. “I can remember the jackup. Tom McDonald (now owner of Oliver’s Cabaret) was waiting for the Listener when it came off the press with the voting forms inside. He was their manager, and he used to buy 15,000 copies of the Listener and then he’d vote them all, put them all in envelopes and they’d go up to Auckland.

“We used to say ‘You’ll never do it, Tom’. He said ‘You watch’. Sure enough he got the Gold Disc.”

As for the Quincys, who had some success with songs such as ‘Aire Of Good Feeling’, ‘In The City’, and ‘Ride The Rain’, they “used to plod along, do our own thing. We didn’t have any managers or anything. Just corner boys.” The Quincy Conserve were out on a limb as New Zealand’s only jazz-rock-pop band with horns. The Upper Hutt boys such as The Fourmyula – who were New Zealand’s top band with hits like ‘Nature’, ‘Otaki’, ‘Come With Me’ and many more – were another distinct scene. Then there was The Avengers, The Dedikation… and on.

What Happened & Why?

THERE ARE SEVERAL linked theories, which all appear to hold water. TV producer, music commentator and ex-group leader Simon Morris says the bands changed from singles to album artists to accommodate shifting audience demands. Bands had to write their own songs or they were no longer seen to be credible; these factors caused radio to lose interest, and a casual downwards spiral continued.

Others blame the end of 6pm pub closing. People were no longer content to spend their time in non-alcoholic clubs swigging coffee.

This shut down clubs, and split audiences into two categories: underagers (who have never since had satisfactory ongoing venues) and pub-goers.

The breweries built big venues to cater for large audiences and entertainment and the bands moved in. With the clubs gone, the bands were in an unexpectedly vulnerable position. Unscrupulous management meant that they had to do more than make their keep; music wasn’t the mainline anymore so much as an expendable backdrop to a drinking scene. The bands also became cut-off from their faithful lifeline, the teenage audiences.

Rick White reckons that the environment in the independent Auckland studios was more relaxed: “You had to deal with a guy wearing a suit and tie if you wanted to record in Wellington”, he says. White also mentions the support of Radio Hauraki at that time for local artists as being a major boost for the Auckland scene.

With artistic career prospects drying up, our best musicians either followed the drift – sometimes overseas – or ended up playing pubs for audiences that really didn’t care anymore.

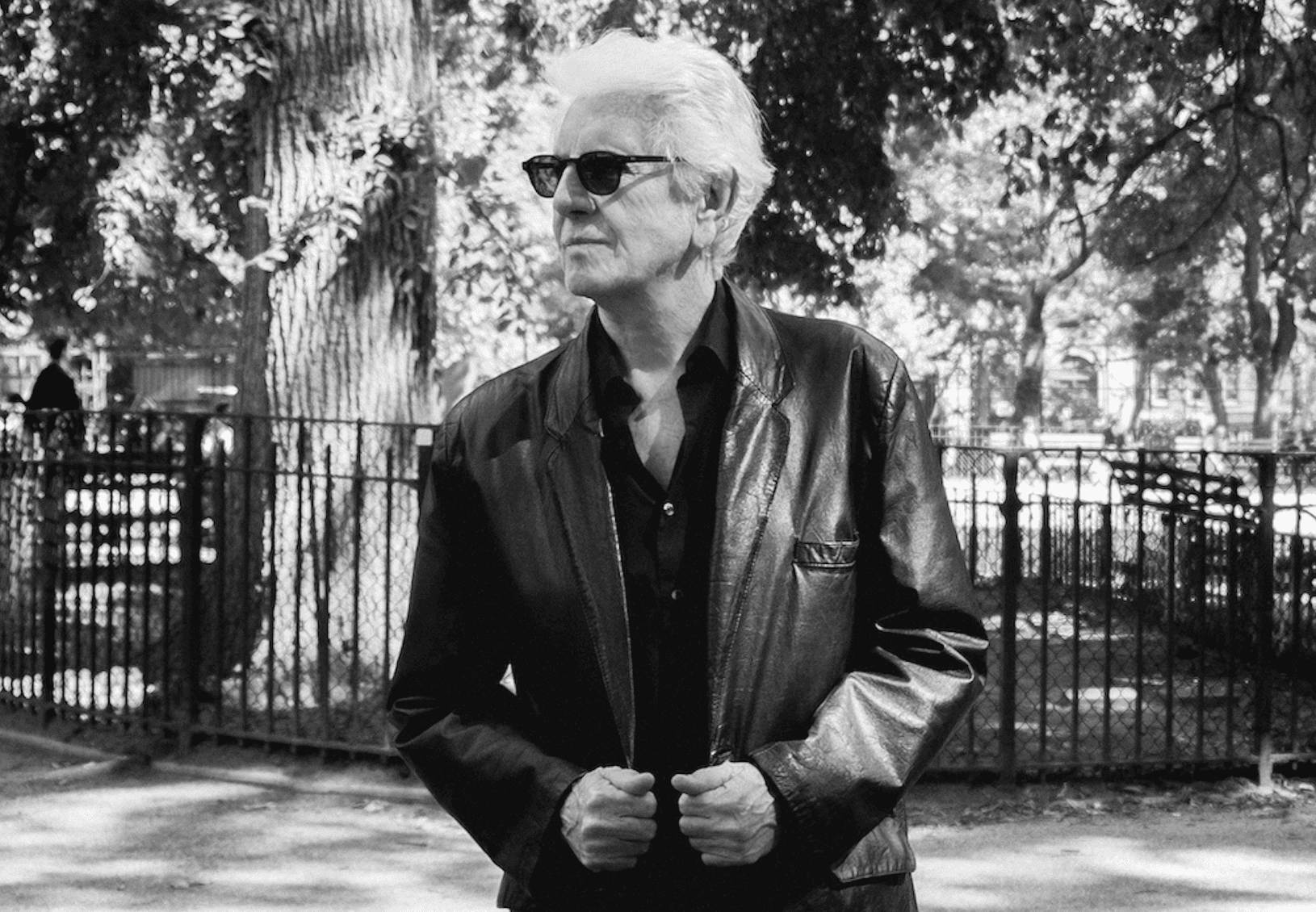

This was the plight of Malcolm Hayman and many of his contemporaries. In any other country the man would be celebrated and respected. Here he is almost unknown now. This can also be attributed to the lack of regular media coverage over the years. The Sports Post ran substantial articles in the ‘60s, but today the amount of serious music coverage is minimal in comparison to other countries.

Rick White says: Things got very technical. Marijuana and big stereos killed it. All of a sudden it wasn’t naïve anymore. People were sitting at home and smoking dope and listening to Genesis and Yes on big stereos.”

Malcolm Hayman: “I think the main problem now is people just don’t go out. It takes a name to draw them now, and that’s a problem for local musicians because they don’t get the work when they first start, so they don’t get the experience.

“They’ve got to fight all the time for work where they should be able to, somehow, playing to audiences that are respectful of what they are trying to do. You can’t get good without being bad first, but no one seems to realise it.”

Featuring Bruno Lawrence (yet again!), Geoff Murphy, Corben Simpson (one of our most neglected and talented songwriters), saxophonist Greg Taylor and Beaver, the troupe criss-crossed the country in a multi-coloured bus, presenting shows with elements of theatre, film and music. 1971 was truly the year of BLERTA, and also the year of acid (LSD). Current 2ZB Promotions Manager Graeme Nesbitt ran an arts festival featuring the group, which was dubbed the ‘trip of a lifetime’.

But these strands of life withered away, as the members began to specialise; Geoff Murphy becoming more involved in film, Lawrence in acting. Greg Taylor wound up as a journo in Sydney.

There was a revival of this spirit in the late ‘70s with the advent of Red Mole Theatre, which was a runaway success and resident at Carmen’s Nightclub (now Spats) for months on end in 1979. People from this aggregation ended up in The Drongos, Coup D’Etat and other well-known groups.

With the total fall-off in audience interest and a hole in the artistic sense, the creative side of Wellington contemporary music-making was left to amateurs in the late ‘70s. The punk ‘revolution’ brought hundreds of hobbyists out of the shadows; few had musical chops, or indeed any appreciation of the local music heritage. “There are a lot of guys who haven’t done their homework”, says Rick White. He proposes that if you haven’t got the hops and attempt to write a song, then you necessarily write within your limits, but “if you copy your idol you extend yourself.” He admits, however, that this would apply if your idol was Hendrix, not Simon Le Bon.

Some great music resulted from the DIY attitude, but ultimately the music was specialized to a degree that a small population couldn’t appreciate.

Sys Malcolm Hayman: “I don’t think a lot of people really give New Zealand musicians the credit that is due. We’ve got such a small population that every band in this country’s got to please somebody sometime or they don’t get anything, whereas in Australia you can specialise. You only need a little section of Sydney to like you and you’ve got enough people to follow you and keep you employed, whereas if you have a small section of Wellington you have two people every night.

No Time Like The Present

WHAT OF NOW? One has to appreciate that a general deterioration has taken place. Not only is the Capital not the music centre, but it is fractured and somewhat barren of opportunity. Most of the old guard assess the scene in bleak terms.

Television is acknowledged as an influential pop medium, and there exists an Auckland lobby propagating the idea of bringing back the days of C’mon; the problem being that the current pop programmes consist of back-to-back video clips, and local bands cannot afford them.

But there’s still a creative independence; one that bands like the Braille Records collective (Primitive Art Group, Four Volts, etc) can grow in. The six-year survival of The Spines testifies to the possibilities of achieving artistic, if not commercial, success in Wellington.

The stars of the original scene are either still eking out a living in pubs, working in related industries, or doing other things. Hayman is semi-retired and performs on an irregular basis with Captain Custard, a four-piece rock band instead of the ambitious outfits he once managed: “It’s not the ideal end of it all.” Rick White makes furniture.

Hayman reckons that “anyone who gets reasonable goes overseas immediately.” He regrets going overseas and coming home again. “Unfortunately I went and came back, which was probably the worst thing to do. I should have gone and gone!” And look at the thanks he got for staying.

White’s current assessment is even more bleak: “I suspect the future holds… not a great deal.”

Contemporary scenemakers are more positive, though realistic. On the live side of life, David Hyams, who runs the Cricketers Steinie Bar, sees the past three years as a struggling time with many good bands coming and going.

He lists The Neighbours, The Jivebombers, The Pleasureboys, The Miltown Stowaways, Big Sideways, The Body Electric, Moving Targets, Hip Singles, The Bronx, Naked Spots Dance, Daggie & The Dickheads, Precious, Two Armed Men, The Grammar Boys, The Wastrels, The Pelicans, Coconut Rough, Circus Block 4, The Willie Dayson Blues Band, The Economic Wizards, and The Tin Syndrome as bands who have played at his venue in the past three years and no longer function for financial reasons.

He blames high touring costs (PA’s, accommodation) and lack of available radio promotional co-ordination for the dropping success rate of local bands.

“Being on the road is hard, physically and emotionally, just earning enough money to feed yourself,” he says.

Hyams, who came to the Cricketers via a term handling Victoria University Orientation and ownership of Wellington’s first vegetarian restaurant The Kumquat where he “tried to re-create the very casual environment” of the Chez Paree club, stumbled across his current work trying to find a venue for The Willie Dayson Blues Band to play at. He found: “I could make more money booking bands than working for 2ZM”, where he was selling advertising at the time.

He puts the ongoing touring band situation at the Cricketers down to the fact that it’s not a brewery-owned pub Hyams says that the average pub manager’s prerogative is to make more profit; the attitude is that cutting down entertainment is seen as a way to more profit.

Hyams contents that the tough licensing laws here have forced music into the pubs, and that the remaining licensed clubs “are not interested in touring bands… Exchequer takes the occasional punt on a Sunday night, which is a dead night anyway.”

Touring bands are therefore given little option. They’re left with one of the several small pub gigs, the cavernous University Union Hall (which is currently under serious review after damage at a recent gig), the old St James (itself under threat from demolition) and the old Town Hall. Hyams describes the rent on that venue as exorbitant. It went from $750 to $1500 a night overnight last year, which has made it impossible for local bands to even contemplate playing there. As always in Wellington, there are a few fledgling possibilities for venues, but it’s not getting better fast.

A proper pub gig constitutes a mid-week session climaxing in a rip-roaring weekend. The early week nights “you played for a roof over your head and a meal, and the gigs you did in the latter half of the week made it feasible.” Theoretically.

But with the pubs wanting to cut costs, the early weeks began to dry up. Malcolm Hayman speaks:

“They’ve (the pubs) got the local mentality of if it doesn’t work we’ll cut it down’. If you play Thursday Friday Saturday, Thursday doesn’t have so many people so chop it out. But I’ve found if Thursday doesn’t go well, you open Wednesday. If you cut Thursday out, Friday drops.”

He describes the dilemma as akin to the current Railways crisis: “Like the train services they cut them back all the time. Once you start doing that no one can catch a bus or a train, so they don’t go on the damn things. They make other arrangements. Kiwi mentality is the only thing I can put it down to.”

Hayman also accuses pubs of being greedy. He can remember playing at the Western Tavern: “We were drawing 2000 people a night at $1 a head and we were getting paid $500 a night. So where did the other $1500 go?”

The recording scene, however, isn’t quite as negative. Frontier Studio began nearly a year ago as an 8-track facility with a mind to being within the reach of local band budgets, and it’s already set to install 16-track equipment.

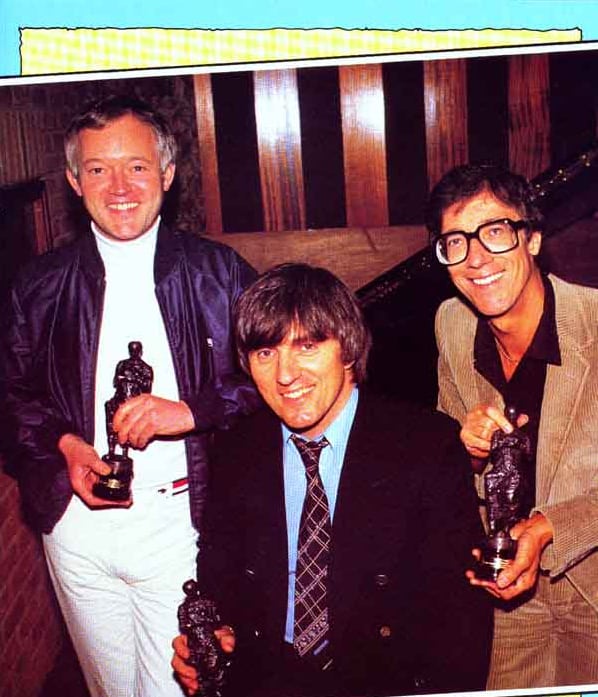

Likewise, Jayrem Records, which celebrates its fifth birthday this year, is doing very nicely.

Jayrem boss Jim Moss – who came into music by singing in a band of Shadows emulators called The Tellstars, and then an involvement in record wholesaling and retailing – sees the thing positively but with a slightly jaundiced perspective.

While encouraged by “the people that come out of the woodwork with tapes”, he finds the inexperience very frustrating to work with.

“The major disappointment is a certain lack of commitment to stick at it. They expect too much too soon, and when they’re only just beginning to develop their own style they break up.”

The problem as Moss sees it could be put down to the lack of any structure, limited finance, no ongoing reliable live scene, and the record companies forever running hot and cold.

Says he: “If someone is going to make a career out of being a musician they’ve got to sit down, decide ‘This is what I want out of life, this is where I want to be in three year’s time.’ They should set objectives. They should be realistic.”

He can operate on an independent record label budget comfortably, whereas the majors, he says, have a problem when it comes to local acts.

“They have the whole corporate thing. They’re run by accountants who are interested in top 10 acts, they’re not interested in cultivating new people anymore.”

And it all comes down to local radio. “We have the ability to make those good pop songs,” he says of the golden days of NZ pop. “they’re not being recorded because the industry is not prepared to put money into it while we have the radio stations. To go and spend $5000 on a single and to have some snotty-nosed programmer tell you there’s not enough bottom end on it, or that it didn’t research well, is heart-breaking. I’ve had it happen too often. I would rather re-direct my energies so that I didn’t have to rely on radio.”

Which is of course what he has done. Ultimately, Moss concedes that the population is not big enough to sustain an industry at present.

Jayrem’s big push is the selling of their record overseas. At press time Moss had just returned from a successful selling spree at the international music market Midem. The big selling factor for Jayrem is New Zealand heavy metal, which goes down extremely well in other countries. And, of course, Wellington – or more specifically the Hutt – is the centre of heavy metal in New Zealand.

Wellington’s – and indeed New Zealand’s – music scene deserves a thorough search through the back pages. There’s a history in need of the telling, and lessons to be learnt so they don’t become stumbling blocks the second or third time around.

In the meantime, the new strategies being applied are both more and less ambitious than in the days of yore. And definitely more realistic. GARY STEEL

Note from the author: What an epic. And how strange to read about a Wellington that no longer exists. RIP Malcolm Hayman. The intro to this piece got me into Pseuds Corner in Metro magazine.

* Don’t forget to check out www.audioculture.co.nz, where you’ll find a vast repository of NZ music history.