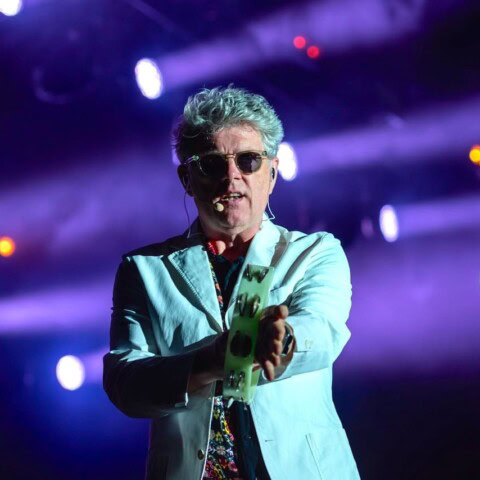

Twenty years ago, GARY STEEL interviewed fascinating Rome-based UK-born folk experimentalist Mike Cooper on one of his Pacific journeys. Here’s that story followed by the full interview transcript.

While the mainstream music industry crashes, burns, and clunkily consolidates in a vain effort to hold onto its shares in a seemingly dwindling market, there’s a worldwide resurgence of a genuine musical culture once considered marginal. A groundswell of young artists like Jodie Holland and the American ‘free folk’ movement are finding their inspiration in American mountain music, raw blues and English folk styles from the ’60s and ’70s.

While the mainstream music industry crashes, burns, and clunkily consolidates in a vain effort to hold onto its shares in a seemingly dwindling market, there’s a worldwide resurgence of a genuine musical culture once considered marginal. A groundswell of young artists like Jodie Holland and the American ‘free folk’ movement are finding their inspiration in American mountain music, raw blues and English folk styles from the ’60s and ’70s.

Occasionally, one of their obscure progenitors is still alive and kicking. This is your life, Mike Cooper. This 63-year-old Rome-based, British-born guitarist, composer and label-owner spends half the year as a performing nomad, culminating in his annual trek through the Pacific Islands, which involves a habitual New Zealand stop off for a series of low-key gigs. Cooper chanced across NZ in 1994.

“I played an acoustic slide guitar for a long time, and discovered one day that the way I play it, the lap style, was a Hawaiian invention. So in 1994 I traveled around the Pacific Islands, staying in each place for a few weeks.” One of those destinations was NZ, which he still considers “a Pacific Island with all you white people living on it. Initially, there wasn’t a lot here for me, just this strange folk club scene, but over the years it’s been fascinating watching the underground and improvising scenes growing exponentially.”

One of Cooper’s mind-altering experiences here was discovering the haunting re-imagined Maori music of Hirini Melbourne (RIP) and Richard Nunns, the latter of whom “eventually came to Rome with Moana & The Moahunters on a tour. While he was there, I organised a gig, and we did a live CD together.”

One of Cooper’s mind-altering experiences here was discovering the haunting re-imagined Maori music of Hirini Melbourne (RIP) and Richard Nunns, the latter of whom “eventually came to Rome with Moana & The Moahunters on a tour. While he was there, I organised a gig, and we did a live CD together.”

This interest in the Pacific culminated in three critically acclaimed releases on which Cooper came up with a bewitching blend of ambient guitar and electronics, mixed in with environmental sounds recorded throughout the islands. But this exceptionally eclectic musician, who considers that “sequels are obituaries”, has already moved on. His current performances anywhere and everywhere (in New Zealand at the likes of the Devonport Folk Club, K’Road’s Wine Cellar, the Moving Image Centre and at Wellington’s Happy venue) are beginning to reflect the entirety of his interests, mixing drifting ambient sections with haunting songs.

From a starring role in the British blues boom of the mid-’60s (his first record release was 1963) to a singer-songwriter career in the ’70s and on to free jazz and beyond, Mike Cooper has never seen the point in inhibiting his musical evolution. “The worst possible thing that could happen to you really would be to become popular, because then you’re stuck with it,” says Cooper. “The underground is hope.” See you next year.

Note: I first encountered Mike Cooper around the turn of the century when he turned up at the record store-cum-venue I was then running, Beautiful Music on K’Rd, expressing interest in performing there. As was his wont, Mike’s tour was low-key and off-the-cuff. At my shop, he performed an improvised set using dark drum and bass loops created by his Italian friend Eraldo Bernocchi, with an old silent film projected on the wall. The audience was disappointingly small. In 2005 he turned up again so I took the opportunity to interview him. I loved the way he managed to fuse folk music stylings with improvised music in a very different set than the one in my shop a few years earlier. Over the years, Mike’s stock with music media has continued to rise, with his mid-’60s folk/blues releases being reissued and reassessed and a multitude of releases, both historic and contemporaneous, emitting from Mike’s own label as well as other cool imprints. Now based in Greece, in 2025 Mike Cooper is still going strong.

Mike Cooper Interview Transcript 2-3-05

Mike Cooper Interview Transcript 2-3-05

Mike Cooper – Major record companies are complaining about not selling any records. The interesting thing is that everybody else is, as far as I can work out. Small labels are selling, independent music is selling, underground music is selling, which is maybe why the majors aren’t selling. They want to hide the fact that this other music scene exists, I think.

Gary Steel – So it’s under the radar because it doesn’t bother participating in this old-fashioned methodology.

Mike – Absolutely. They don’t want to participate in the mainstream. Except it might be good to get on the radio now and again. But maybe not, it might ruin the whole thing (laughs).

Gary – You’re in a unique situation to observe and comment on all this, because you’ve circumnavigated the whole scene for such a long period of time, and gone through so many phases of your own work, and had some dealings with the majors as well.

Mike – Initially, I did. I worked for Pye for a long time. [One of the major British labels of the late ’60s/early ’70s]. That worked for as long as it worked. When [Pye’s “pretendependent” imprint] Dawn ran out of steam, Pye ran out of steam at the same time, they collapsed completely after Dawn collapsed… their selling label was the one they didn’t want to know about, absolutely.

Gary – It wasn’t Dawn that sank Pye?

Gary – It wasn’t Dawn that sank Pye?

Mike – Exactly, ‘Dawn Sank Pye!’ But we sold records, though. We did sell records. We weren’t pop star level, we weren’t selling like the Kinks were, who were also on Pye. We were ultimately more interesting, I think, though I do like the Kinks. The first record I made wasn’t on a major label, though. I made it on a label that ostensibly would have been an independent label, a label that made records of the sound of barges going up and down canals, and steam trains and things like that. And [the owner] used to come along to the folk club, and he said one day, ‘Have you ever made a record?’ And I said ‘You’re kidding!’ and he said ‘You should make a record!’ So that was an independent record label to start with, that’s where my career started, I started up where I ended up.

Gary – What year was that?

Mike – 1963.

Gary – You’ve gone through this incredible process and observed it all. Do you think it’s a better life, to be operating in the underground as it were? You’ve somehow managed to keep it all afloat. Is that the road you’d choose if you had it all over again?

Mike – Absolutely. I’d advise anybody to do that, in fact. The thought of fame and fortune, if it ever crosses your mind, is the one you should never have. My last dealings with a major label were when I was working for Nato, that French label, a small independent label, which suddenly decided to get distribution through Harmonia Mundi, and did my Island Songs record through them. It cost a lot of money to do that record, thinking that Harmonia Mundi would sell the thing, but they had no idea what to do with it. Harmonia Mundi was either a jazz label or a classical label, and had no idea what to do with me. What happened was that they never sold anything. I sold more CDs at gigs than they sold. So ultimately I thought ‘I’m better selling CDs at gigs’. I don’t even press the things. I do them at home. I was thinking about doing this for a long time, and then I bumped into Eugene Chadbourne, who’s been at it for years, and he said that’s the way to go. Doing it yourself, you don’t have anybody telling you anything. If you want to change direction overnight, you change direction overnight. If you want to get up in the morning and make a record, you can get up in the morning and make a record. You can make five a week, seven a week, depends on how hard you can work, if you want to do that many. Stick ‘em on a table; if people want to buy them, they buy them. Artistically, there’s nobody telling you what to do. As you know, I work so broadly, there’s no other way I could do it. No record company would deal with me, playing country blues one day and free electronics the next day. It’s ultimately more interesting, more interesting for me and more interesting for everybody else, I think. What’s interesting on the radio? Practically nothing.

Gary – Do you think that the conventional way of doing things somehow legitimises the process for a lot of people?

Gary – Do you think that the conventional way of doing things somehow legitimises the process for a lot of people?

Mike – They think it does, you mean.

Gary – A chap who used to work for me in the shop, still, after all these years, screws his nose up at a lot of the underground stuff, that hasn’t been produced in a grand studio and hasn’t got a grand cover and isn’t mass-marketed, and is therefore not legitimate.

Mike – There are some people working in the underground who think like that. I don’t want to name any names, but I had a well-known record distributor/underground person who said to me, ‘We don’t sell CD-Rs’. I said, ‘Why don’t you sell CD-Rs?’ and he said, ‘I know what you people do! You go out and buy a pack of CDs that cost 15p each and try and flog them off for 10 Euros.’ You’re supposed to be on my side, what are you talking about! Especially as that particular person used to do it himself.

Gary – I guess we’ve been sold the artifice for so long, going back to the origin of contemporary culture, really. Patronised by kings and queens.

Mike – Now it’s like corporate patronisation.

Gary – Teenagers very happily wear labels.

Mike – They love wearing labels all over their chests and bags. They’re walking hoardings (laughs). I always try and get supermarkets to PAY me to carry the plastic bag around (laughs). I always turn it inside out before I come out of the shop.

Gary – I find it endlessly fascinating that, especially working in the media, and coming up against resistance from editors over the years when I’ve written about musicians who don’t fit into those traditional areas. Such resistance from people who are otherwise quite intelligent human beings, and you start to wonder what’s behind it. What’s going on with their mindset there? And you get people like young Sam here, whose whole LIFE revolves around the underground, as a consumer and player as well.

Mike – It’s not all gloom and doom, though, because I’m fascinated at the moment, I discovered a couple of months ago that there are these people selling off old vinyl cutting machines to artists who are then cutting live records and selling like 25 copies. $200 each. These art pieces. There’s a whole scene doing that, which is fascinating. Apart from the other vinyl scene, which is going on unbeknownst to Mr CD maker on top of the building over there, who has no idea or who is pretending not to know. People are buying vinyl and turntables and still playing records.

Gary – Do you think perhaps that some of this misunderstanding might have to do with those traditional notions of art and culture versus pop… high and low culture? I know even with this thing I’m writing in Metro, we’re dealing with an Arts section of the magazine and on the front page of the arts section, they’ll talk about some symphony thing, high culture, on which they’ll quite happily put something obscure. Then some high art. But when it gets to the music page, somehow it’s legitimised by being pop. Perhaps people are still scared about thinking of contemporary music as being part of the fabric of their lives, as opposed to being confused about whether it’s supposed to be important, or have cultural validity. You’re a living example of this kind of stylistic… putting everything through the stylistic shredder, really.

Gary – Do you think perhaps that some of this misunderstanding might have to do with those traditional notions of art and culture versus pop… high and low culture? I know even with this thing I’m writing in Metro, we’re dealing with an Arts section of the magazine and on the front page of the arts section, they’ll talk about some symphony thing, high culture, on which they’ll quite happily put something obscure. Then some high art. But when it gets to the music page, somehow it’s legitimised by being pop. Perhaps people are still scared about thinking of contemporary music as being part of the fabric of their lives, as opposed to being confused about whether it’s supposed to be important, or have cultural validity. You’re a living example of this kind of stylistic… putting everything through the stylistic shredder, really.

Mike – (Laughs). There’s a strange contradiction in it all, though, because the corporate world… the magazine represents the corporate world, ultimately, it’s a glossy thing. It has this page it calls ‘Pop’… What pop used to be was something that was quite edgy. Now pop is very, very safe. On the other hand, the corporate world is in fact the one that is keeping the visual art world afloat, basically. The corporate world is the one that is buying all the Damien Hurst, people like that, which is a really odd contradiction. It’s like ‘visual art is okay for the corporate world, but music is this thing that you keep… sweep it under the carpet for Godsake, don’t let ‘em get near that!’ Which leads me to think that one is more effective than the other.

Gary – Music’s a more direct communicator of…

Mike – Visual art doesn’t mean a shit. When it comes down to it. Damien Hurst can saw up as many cows as he likes, and no one cares!

Gary – It’s not thought-provoking in a political sense.

Mike – No. Maybe people are too insensitised for that to have any effect on them nowadays anyway. We turn on the television and see people blown apart for real, it’s not even make-believe any more. And music has far more impact, I think. Music is still able to grind you up the wrong way. You get a good noise band and they’ll flee for the door.

Gary – Why the huge disparity between styles?

Mike – I don’t think there’s a contradiction. I think you can follow through my music bit by bit, and you’ll find it’s all joined together in the end. I’ve been forced in a way to keep it separate for many years. Of late, I’m joining them all together for the audiences. You can come up to the Devonport Folk Club and I’ll play a piece of John Zorn… they loved it! They get into it. John Zorn’s very brief! (Laughs). So it’s all one piece for me, it’s all folk music, anyway. Because of what we’ve been talking about, I think it ends up folk music. I think the underground is hope.

Gary – I’ve just never heard of anyone playing the Devonport Folk Club one minute and Artspace the next and Moving Image Centre or some avant garde festival and… the Hawaiian slack guitar.

Mike – Float between them all. All these stars are all connected by music.

Gary – How do you decide which one you’re going to do?

Mike – Context decides. If I’m at the Devonport Folk Club, they’ve booked me because of a certain aspect of what I do. It doesn’t preclude me from doing something else of the things that I do. And these days they’re happy to come on some of that journey as well. I’m not going to annoy them. The same for the electronic and improvised music audience. The new CD I did… it’s got two very straight songs in the middle of it, by Van Dyke Parks and Fred Neil. I’m hopefully bringing it all together now, won’t be so DIS-PARATE. I just keep adding to the pile.

Gary – Your interest in the Pacific, how did that come about?

Mike – I played an acoustic slide guitar for a long time, and I discovered one day that it was a Hawaiian invention, stylistically, not an Afro-American invention, especially the way I play it, the lap style, is Hawaiian. And I investigated that, and from that I discovered the slack key Hawaiian music and all the other Pacific musics, and then I CAME to the Pacific. I then discovered all the other aspects of its culture as well.

Gary – When did you first come down here?

Mike – 1994. I went to Los Angeles to Tahiti, Fiji, Rarotonga, New Zealand, Australia, then back via Hawaii. Stayed for a few weeks in each place.

Gary – Does New Zealand feel like a Pacific Island to you?

Mike – That trip it did, because I only went North of Auckland. I thought the whole of New Zealand was like that, I didn’t realise the bottom of it was like Scotland. Yeah, of course, it is! (Laughs). To me it is. It’s a Pacific Island with all you white people living in it.

Gary – Apart from the discovery of the guitar music, what is it that’s kept you coming back to the Pacific Islands over the years, and why did you end up doing music that explores Pacific themes?

Mike – I got very interested in one specific person in Hawaiian music, who I think was a great composer and arranger of Hawaiian songs. Arranging seven guitars playing music was fabulous, I think. Apart from Hawaiian music, I was very interested in Fijian music, which is the nearest thing to skiffle I’ve found, which is the roots, as far as I’m concerned, to rock’n’roll. Fijian music is where it’s at! Nobody’s ever put out any LPs of Fijian string bands, it’s phenomenal, they completely ignore it, and it’s GREAT music. I’ve been going to Australia and New Zealand for 10 years now. I was completely blown away by the sonic soundscape of Australia, particularly the wildlife thing. The birds aren’t so exotic here in New Zealand as they are in Australia. The soundscape is phenomenal in Australia, and I ultimately began using it in my music. A few other things, I began doing things with musicians over there.

Gary – I read recently that in the 1800s, the New Zealand bush was still really noisy. The possums and ferrets and so forth have killed it off.

Gary – I read recently that in the 1800s, the New Zealand bush was still really noisy. The possums and ferrets and so forth have killed it off.

Mike – A lot more going on. I’ve noticed here the birds are really… they fly very low to things, to the ground and to trees, they hide incredibly, whereas Australian birds are really out in the open. Very noticeable difference. They’re a bit like Italian birds, which get hunted as well. Close to the ground.

Gary – What about New Zealand? What’s here for you?

Mike – Initially, not a lot. But there’s this strange folk club scene, which was and still is really traditional. But over the years I’ve been coming here, I’ve been fascinated watching the underground and improvised scene grow here. And when I first went to Australia, there was hardly any experimental scene. Here it’s grown exponentially. When I first came to Auckland, there wouldn’t have been anything to do in terms of that scene. Your shop was where I went to; that was the only place here when I first came here. There was nothing in Wellington, then Space opened up, then Happy, several nights a week, three gigs a night, which is fantastic.

Gary – Haven’t you worked with Richard Nunns?

Mike – Yeah, of course. I discovered Richard Nunns in Real Groovy Records. I went in looking for local music, and found a tape with some Maori words on it, and I took it home and was astounded by this music I was hearing, which was contemporary music as far as I was concerned. So I hunted him out. It took me five years to find him. And then it was purely by chance. I was in Nelson and started talking about him, and someone said he lived up the road, so I went and visited him. He eventually came to Rome with Moana & The Moahunters on a tour, and while he was there, I organised a gig, and we did a live CD together. We’ve played together in Wellington three or four times together… I did a gig with him last week.

Gary – What are the plans? The life of a musician who works this underground circuit and invariably comes down to Australasia every year. Do you have five-year plans and strategies?

Mike – (Much laughter). Five-dollar plans!

Gary – You seem to enjoy your life.

Mike – I do. I did an interview recently where the interviewer asked, ‘Was your decision to move from playing blues to improvisational music a financial one?’ (laughs). And I said, ‘Yes it was, I decided on a financial disaster!’ I couldn’t believe it! No, I work at a yearly plan of gigs.

Gary – I’m interested in how you plan and structure it, because if I was in your situation, being the stolid individual I am, I’d be stuck in my abode in Rome churning out new CDs and I’d never get out of the room, let alone the city (much laughter).

Mike – I tour about six months of the year, and stay at home about six months of the year. I like staying in Rome in the summer, I enjoy summers there, and while I’m there, I do tons of recording, so most of my recording is there, a bit of writing. All the stuff you do at home, I do there. Then I go on tour. Two or three months, I’m usually down in New Zealand and Australia. And then I charge around the rest of Europe. I do quite a bit in Rome, we’ve got two or three clubs going. I don’t do many club gigs in Rome, because the clubs close in Summer, it’s a festival scene.

Gary – You don’t play in England?

Mike – Occasionally. I go over once a year. But it’s not a big scene in England. It’s a very influential scene, but it’s quite small around London. There’s a scene in Scotland at the moment, it seems to have taken over as the cultural centre of the British arts. Dean Roberts was over there in Glasgow recently.

Gary – Are you still living, breathing, listening to music all the time, or are you a bit like Toop… I remember reading a thing of his about how he’s sick of music.

Gary – Are you still living, breathing, listening to music all the time, or are you a bit like Toop… I remember reading a thing of his about how he’s sick of music.

Mike – Yeah, he doesn’t listen to music. I listen to music all the time. I’ve been listening to a lot of John Fahey recently for some strange reason. I’ve rediscovered John Fahey. The Great Sacramento Oil Slick, a live recording they just found. Fantastic. I got interested in playing the guitar again, in fact. Because I have all those interests, musically, it keeps me going, because things come and go. I’d lost interest in playing the guitar, some while ago, as a guitar. I used it as a sound source. And then, suddenly, last year I put on an old John Fahey record and thought ‘playing guitar is a really nice thing to do’. So while I’m going around on this trip, I’m trying to make a solo acoustic thing in people’s houses. One in each house. So it kind of feeds itself, I think, which is good. Because if I had only played guitar, I would have stopped, because I lost interest in it. That’s probably what’s happened with Toop, he’s fed up with playing records.

Gary – He only wants to hear the good stuff, but you’ve got to spend time sorting out the wheat from the chaff. I know what he’s talking about in terms of… sometimes your sensibilities are shattered by the meaningless noise of it all, and I often prefer just listening to the environment. Not cicadas, I’ve already got tinnitus! Maybe crickets!

Mike – Yeah, I don’t really understand why Toopy gets bored listening to music. Listen to something else!

Gary – One of my frustrations is the lack of time to hear my favourite records MORE. It’s one of the great things about records.

Mike – My listening is seasonal as well. I tend to listen to tons of Hawaiian music in the summer, then in the winter go into this hibernation mode and listen to hibernation music, whatever that is! Stay at home music.

Gary – My ears work better in winter. I’ve always got a bit of hayfever in the summer, and it blocks my sinuses. I’ll make this my last one, but can you imagine a career where the singer-songwriter part of your career, where you were making records in the early ’70s, can you imagine – as it did with a lot of people – that continuing as a continuing current to now? Could that have ever happened to you?

Mike – No, I’d have gone NUTS.

Gary – I notice Donovan hasn’t done much lately. (Laughs)

Mike – And a few more besides! That would have been death. I used to think about that, because the worst possible thing that could happen to you really would be to become popular, because then you’re stuck with it. It even functions for me on an extremely low level. That Rayon Hula CD for me was very successful. It was very tempting afterwards to do another one. But then I thought, ‘What are you thinking about?’ It’s like the carrot, ridiculous. It’s like you get great reviews and you sell a few and you think ‘that works!’ Okay, forget it! That’s my reaction. Sequels are obituaries. A career as a singer-songwriter, that would have been terrible.

Gary – I’ve got a lot of singer-songwriter stuff from the ’70s that I love, but they’re very seldom people that I’ve followed through for a long period of time.

Mike – I followed Bob Dylan up to a point, but then lost interest.

Gary – I’ve got all the Roy Harper, I have to admit!

Mike – (Laughs) Roy’s great! Still is! I’m glad you like Roy Harper! I like a lot of the young singer-songwriters as well. I’m just discovering this new crop of singers, like Jodie Holland, I really like that. And Judy Welch.

Gary – It’s interesting that these people are basically 20 years after the event, and clueing in to things that happened back then.

Mike – Even longer than that, 30 years. Even Dean, who got me to do this gig, got into me through my old records. He found a bunch of my LPs in Bologna, and went, ‘Who is this guy?’ and the guy he was staying with in Italy happened to know me. So that’s been very interesting for me. That’s happened a lot for me recently. Do you know Matt Valentine in the States? He plays in a band called Towering Recordings – he’s another one who found me through my records, and found out I was still alive. It’s kind of like me finding a Robert Johnson record when I was the same age as them, he was 30 years [before], it would have been exactly the same time span.

Gary – It seemed in the ’70s and ’80s, except in a clichéd and limited way, there wasn’t much interest in the real underground of the ’60s and ’70s. The British folk revival is really interesting. A lot of American bands are into it. I used to feel EMBARASSED that I owned some of that stuff as an ardent NME reader, because as far as they were concerned, British folk was… they’d make jokes about Morris dancing.

Mike – Matt Valentine and those guys are into Gary Davis. They’re doing their posters and records like old blues records. It’s odd, but great. They’re making artefacts. They do limited vinyl.