IT’S ALWAYS HARD when a novice asks for advice about the “best” Frank Zappa albums. Ironically, the biggest obstacle is the fact that Zappa is almost unique amongst pop culture icons in churning out product of remarkable quality throughout his too-short life on earth. The thing is, this only becomes obvious once you’ve put the hours in, listened attentively to the whole catalogue, and done the requisite research. It’s knowledge that comes through appreciating what Zappa referred to as conceptual continuity – ongoing linkages from one project to another that kept the whole oeuvre relevant, despite what to many seemed like complete stylistic disjunctions.

IT’S ALWAYS HARD when a novice asks for advice about the “best” Frank Zappa albums. Ironically, the biggest obstacle is the fact that Zappa is almost unique amongst pop culture icons in churning out product of remarkable quality throughout his too-short life on earth. The thing is, this only becomes obvious once you’ve put the hours in, listened attentively to the whole catalogue, and done the requisite research. It’s knowledge that comes through appreciating what Zappa referred to as conceptual continuity – ongoing linkages from one project to another that kept the whole oeuvre relevant, despite what to many seemed like complete stylistic disjunctions.

Try to explain this to a novice, however, and their eyes tend to cloud over rather quickly. People expect an artist’s best work to be found on two or three representative discs, and that’s just not the case with Frank Zappa.

It is true, however, that when people want to hear why Zappa is so great, We’re Only In It For The Money is one of the albums I always recommend. It’s not that it contains everything about Zappa’s artistry that a listener should be aware of, because it doesn’t. There’s little of the instrumental dexterity found in his ‘70s and ‘80s work, for instance, but Money (as I’ll refer to it henceforth) is possibly the most coherent stand-alone statement that Zappa ever made, as well as being a sustained compositional and lyrical work of genius. So yeah, everybody (even non-Zappa fans) needs to own (and listen, over and over and over) to this remarkable record.

There are scholars who are more well qualified than me to explain exactly what it is that Zappa’s doing here (check out James Gardner’s chapter in the forthcoming book of essays, Frank Zappa And The And, edited by Paul Carr), but I’ll try my best to give a general overview in capsule form.

In preparation through 1967 but held up until March ’68 due to record company dithering (ultimately, they censored some naughty words and insisted that the cover, a piss-take of The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band with vegetables and cross-dressing instead of flowers and glamour, be turned inside-out), Money made its predecessor, Absolutely Free, seem like a mere theatrical and under-rehearsed run-through, although that album’s key piece, ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’, was a clear prototype.

Flowers, drugs, ‘dropping out’, dippy pseudo-philosophy, (all you need is) ‘love’; Money slams them all and then goes for the parents, the constabulary, the lawmakers and society in general. It’s an amazing round-up of societal hypocrisy that, while rooted firmly to 1967, still makes sense in 2012.

Those fans of Zappa in the ‘60s who gave up on the ‘70s version will refer to Money as an example of how the composer let his fans down later on with flimsy, dirty little ditties about drooling lesbian sisters and enema bandits and Catholic girls. There’s more to it than that (much more), but there’s one truth about Money that won’t go away: it’s one of the few times that Zappa eschewed the obvious gags and got down to some heart-on-sleeve honest (and often angry) portrayals of society’s ills. There’s plenty of humour here, but it’s mostly in the sounds themselves, while the album contains rare examples of lyrics and songs that are overtly compassionate.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. It isn’t just the fact that with Money, Zappa etched out a sustained set of relatively approachable tunes wed to lyrics that were as close as rock ever got to a comprehensive critical analyses of an important subculture, it’s the fact that he combined that with an extraordinary palette of musique concrete experiments, hundreds of hand-cut edits and a mad-scientist approach to overdubbing.

While the album originally appeared as a work by the Mothers Of Invention, it’s clear that Zappa used the work of his cohorts more as a sample library than as complete performances, as most of the songs are modified to the extent that they sound quite alien: voices are often sped up to sound almost like chipmunks, and the same is true of the instrumentation.

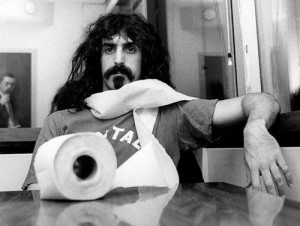

I remember the disappointment the first time I listened to Money. Those chipmunk voices, and the cartoonish quality of the sped-up (and otherwise mutilated) instruments, gave the whole thing a surreal edge that made it hard to take seriously. Where were the heavy rock guitars? But I came to realise that Money lived in its own musical universe, and that it had to be approached as such; and each time I repeated the experience, I heard more in the mix. There’s so much detail packed into this album that you could hear it many, many times without gleaning everything of benefit. [It’s a lesson that the Zappa fan learns over time: that his whole oeuvre is in essence fighting against clichéd ideas about authenticity, both sociologically and in terms of composition, performance and production. But we’ll leave that discussion for another day].

Right from the first notes, Zappa is getting stuck into his target. “Every town must have a place/Where phony hippies meet/Psychedelic dungeons/Popping up on every street”. And later on the same song (‘Who Needs The Peace Corps?’) he gets the hippy himself to spout forth: “I will wander around barefoot/I will have a psychedelic gleam in my eye at all times/I will love everyone/I will love the police as they kick the shit out of me on the street…”

Although Zappa is scornful of the hippies, it’s the iron fist of the law, and a society that allows repression of outsider subcultures, that ultimately gets his ultimate opprobrium. In the very next song, ‘Concentration Moon’, he gets stuck into the heavy handed reaction of the armed forces to student unrest: “American way/How did it start?/Thousands of creeps/Killed in the park/American way/Try and explain/Scab of a nation/Driven insane.”

Weirdly, it was a few years later that the authorities opened fire on demonstrating students at Kent State University, killing four and wounding nine more.

Weirdly, it was a few years later that the authorities opened fire on demonstrating students at Kent State University, killing four and wounding nine more.The invective continues in a strangely subdued and compassionate fashion on ‘Mom & Dad’, where Zappa accuses the hippy parents of neglecting the needs of their kids: “Mama! Mama!/Someone said they made some noise/The cops have shot some girls and boys/You’ll sit home and drink all night/They looked too weird/It served them right.”

The next bit is such classic Zappa that I’ve got to quote it in full: “Ever take a minute just to show a real emotion/In between the moisture cream and velvet facial lotion?/Ever tell your kids you’re glad that they can think?/Ever say you loved ‘em? Ever let ‘em watch you drink?/Ever wonder why your daughter looked so sad?/It’s such a drag to have to love a plastic Mom & Dad.”

The above lines display some of his key concerns, and in different ways, they return throughout his huge discography: the plasticity of society, superficial parental values. And although Zappa has been roundly criticised for his later “naughty” lyrics, there’s a specific morality – and even a rage that’s just kept in check by good humour – that comes through time and time again.

‘Harry, You’re A Beast’ deals with fake ideas of female sexuality, and could be seen as an early portent of the sexually overt material that would get him in trouble with miscellaneous sub-sectors of society during the ‘70s and ‘80s. Musically, it’s brilliant, with its cod-classical piano flourishes and backwards voices (actually the censored line “Don’t come in me!”) and pronounced stereophonic effects.

‘What’s The Ugliest Part Of Your Body’ and later, ‘Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance’, both suggest alternative ways of looking at subjects usually dealt with in clichéd manners. By suggesting that your mind is the ugliest part of your body, and that some utopian time in the future, you’ll be able to take your clothes off and dance, even if you’re FAT, Zappa is subverting the entire emphasis of society on the superficial.

The last two songs on what was originally the first side of the vinyl are both killers, ‘Absolutely Free’ a trippy montage of musique concrete manipulations that’s like a faked hippy kaleidoscope and pre-prep for ‘Flower Punk, a demolition of hippy stupidity that, while based to an extent on ‘Hey Joe’, is an astonishing head-melt of its own accord. Ultimately, it degenerates into a bizarre chipmunk dialogue going on simultaneously in both speakers with loads of effects whizzing around in a disorientating fashion.

Side two, however, is perhaps even more astonishing. It gets underway with a brief musique concrete piece, ‘Hot Poop’, which appears to be mimicking an LSD experience. At one point, Eric Clapton (God’s honest truth!) shouts “Oh God it’s God I see God!” ‘Nasal Retentive Calliope Music’, as the name suggests, ushers in even more crazy sonic shit, and peaks with crashing waves, a brief snatch of surf guitar music, and the sound of a needle jumping over the grooves of a record (ouch!)

We’re back into song-land with the utterly brilliant ‘Let’s Make The Water Turn Black’ and ‘The Idiot Bastard Son’, the first of which tells the (true) story of Ronnie and Kenny saving their “numies” (snot). It’s a darkly humorous suburban story with a hint of gothic horror, until the last verse: “Ronnie’s in the army now and Kenny’s taking pills/Oh! How they yearn to see a bomber burn.” ‘The Idiot Bastard Son’ is a surreal sequel to ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’, where “the father’s a Nazi in congress today”. Musically, it’s tremendous, and lyrically, it goes for that very FZ trick of turning the venom back on the listener: “The child will thrive and grow/And enter the world/Of liars and cheaters and people like you/Who smile and think you know/What this is about/You think you know everything…”

‘Lonely Little Girl’, ‘Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance’ and a reprise of ‘What’s The Ugliest Part Of Your Body’ are so deftly woven together that they’re almost of a kind, and act as a summation of everything that has gone before. The key lyric, which is repeated several times in different songs, is:

“All of your children are poor/Unfortunate victims of/Systems beyond their control/A plague upon your/Ignorance and the grey despair of your ugly life.”

How very Johnny Rotten.

It’s a withering indictment that makes his invectives on hippy culture seem mild by comparison. In other words, he’s blaming a whole generation of parents and their bogus values for “raising up a crop” of children who have reacted against their superficiality with their own set of equally bogus, utopian fantasies that won’t ever amount to anything real.

The album concludes with a piece that makes both the Freak Out! epic ‘Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet’ and The Beatles’ ‘Day In The Life’ seem like playtime. ‘The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny’ is for everyone who ever considered what Zappa did to be comedy only. There’s laughter in it, but it’s not funny. In fact, this inventive evocation of a future none of us want a part of can still chill to the bone. It’s not a ‘song’ and there are no lyrics, and although Zappa uses techniques familiar to the world of “serious” composition, it utterly works on its own merits.

The only real downside to Money is its sound quality. It’s not awful, but clearly suffers from the extensive overdubs and editing that Zappa subjected the original tapes to, as well evidentially poor storage of the master tapes over many years. This latest version is derived from the 1993 master tapes, which Zappa worked on prior to his death late that same year. In 1984, he had controversially recorded new bass and drum tracks, so anyone with the 1987 CD will have the “butchered” version of Money, and should immediately get this version. The complication is that Zappa’s remix re-instated several censored sections from the original, and this version reverts to the censored master. [In other words, the serious Zappa-head needs both.] This time around, the master tapes have obviously been mastered again using up-to-date technology, and the sound is substantively bigger, with more pronounced bass. On ‘The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny’, the difference is most pronounced; where previous versions sounded flat compared to the vinyl, this time, every grain of this head-spinning abstraction is brought to bear in full stereophonic glory.

Happily, the cover art has also been reversed back to the way Zappa originally planned it, with the savage satire of The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper resplendent for everyone to see.

From go to whoa, We’re Only In It For The Money is a masterpiece, its musical genius deriving from its wrangling of coherence from chaos, and its lyrical and sociological significance are something else again. GARY STEEL

Sound = 3.5/5

Music = 5/5