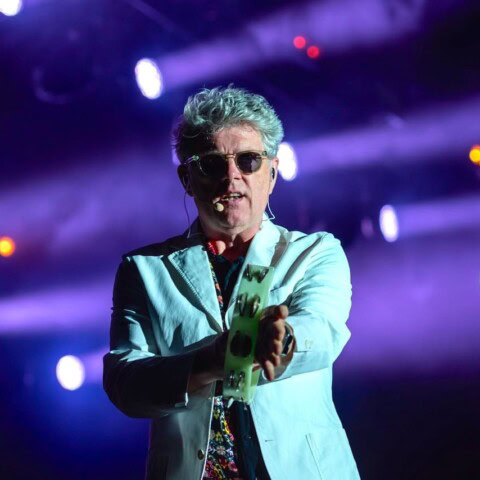

Any prospective fan making their way through Zappa’s bounteous discography needs to know how to find the motherlode, but it’s not easy, writes GARY STEEL.

Frank Zappa was the most prolific artist of the rock era, in his lifetime (1940 to 1993) releasing 62 official albums. Famously, he kept a vault full of unreleased recordings, many of which have been unearthed and posthumously released by the Zappa Family Trust, and distributed worldwide by Universal.

While many major recording artists have had previously unreleased material unleashed on the public after their deaths, and it has become the norm for hugely bloated reissues of physical product for consumption by an audience thirsty for any tasty niblets of their favourite musican, in Frank Zappa’s case this is hugely problematic.

Support Witchdoctor’s ongoing mission to bring a wealth of new and historic music interviews, features and reviews to you this month (and all year round) as well as coverage of quality brand new, contemporary NZ and international music. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

In June this year, for instance, a 3-CD set called Funky Nothingness was released that had reviewers drooling. The lazy repetition of similar so-called evaluations (straight from the supplied publicity blurb) was downright scurrilous. They all said that the largely previously unreleased contents – most of which were recorded the year after Zappa’s widely lauded 1969 jazz/rock-fusion classic Hot Rats – was practically a sequel to that album, and of a similar quality.

The material certainly sounded good, but I believe that Zappa left it all on the shelf for a good reason: they were mostly just spontaneous jams together with some early versions of material that was later fleshed out for public consumption. For hardcore Zappa fans and nerdy completists like me, Funky Nothingness was something of an event, but this collection of tracks was ultimately disappointing, like most of the other vault scrapings.

The material certainly sounded good, but I believe that Zappa left it all on the shelf for a good reason: they were mostly just spontaneous jams together with some early versions of material that was later fleshed out for public consumption. For hardcore Zappa fans and nerdy completists like me, Funky Nothingness was something of an event, but this collection of tracks was ultimately disappointing, like most of the other vault scrapings.

There are now more releases by far from the vault than there ever were in Zappa’s lifetime. A few of them are genuine Zappa albums that the artist had recorded prior to his death, but many of them are either reissues of original albums paired with discs full of demos and alternate takes from the sessions, and there are lots of live albums (some of which feature sub-par performances or include performances that have already appeared on proper Zappa albums).

While it’s easy for, say, a Jimi Hendrix fan to hear the original albums in sequence before venturing forth into the confusing (and mostly unnecessary) profusion of live albums, Zappa’s catalogue is so immense and the way the posthumous releases have been handled and marketed make it horribly confusing for prospective fans to get a handle on what the artist was really all about.

As a Zappa freak from way back, friends and acquaintances often ask where they should start in their exploration of his music. It’s hard enough to guide people to some basic understanding and appreciation of Frank Zappa’s music without having to even think about the glut of multi-disc travesties and bloated boxes that came after his death.

As a Zappa freak from way back, friends and acquaintances often ask where they should start in their exploration of his music. It’s hard enough to guide people to some basic understanding and appreciation of Frank Zappa’s music without having to even think about the glut of multi-disc travesties and bloated boxes that came after his death.

Yes, I’m being harsh about the posthumous stuff but it’s important to get my point across, because there’s something about the 62 (or so) albums that Zappa put together in his lifetime that any fan worth their salt needs to know: that those albums are put together with Zappa’s Conceptual Continuity, or as he more often referred to his overall methodology: Project/Object. I’m going to rub some Zappa fans up the wrong way with this claim, because to many, Conceptual Continuity was just a phrase for a technique Zappa used to create a connection from one album to the next via certain recurring references, like (for instance) Suzy Creamcheese and poodles. To me, however, the term relates to a much greater working methodology and ultimately, right to the core of Zappa’s artistry.

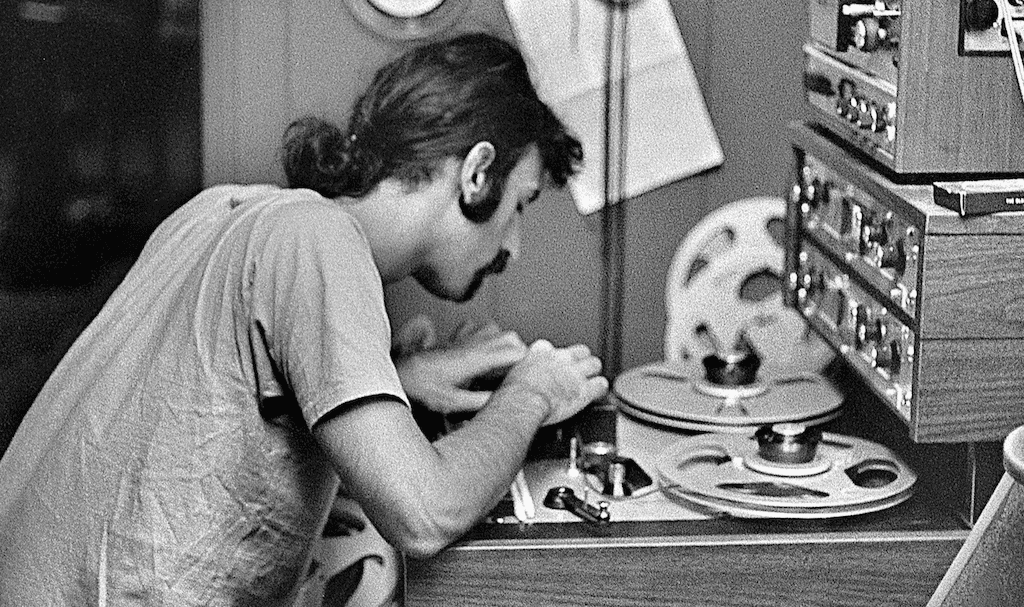

Most importantly, it relates to the way that Zappa edited his records. Zappa’s editing and sequencing skills were a key part of his artistry that seldom gets discussed, possibly because so many of his fans are terminally obsessed with the technical proficiency of the performances or how one guitar solo compares to another. Perhaps the finest example of Zappa’s creative editing skills is his third album, We’re Only In It For The Money (1968). An absolute tour de force, this album (recorded in 1967 and released in March 1968) launched a vicious assault on flower power hippies and is notable in many ways we don’t have the space to discuss here. (But you can check out my review of it here). Zappa’s previous album, Absolutely Free (1967) is the first long player I’m aware of that was segued from track to track, and its highlight, the seven minutes and 26 seconds of ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’, make for a startling entry into Zappa’s universe, containing as it does caustic commentary on the state of US social politics but more importantly, a song that contains multiple outrageous micro-edits with sharp contrasting sections and sonic intrusions. (Check out my review of Absolutely Free here). It’s a masterpiece, and the 39 minutes of We’re Only In It For The Money represent a natural next step with its even more audacious edits, sped-up voices and instrumentation, and generally crazy shit happening all over the show.

Okay, you might be thinking, but surely other psychedelic-era bands, including The Beatles, experimented with sound and form and editing techniques during the late ‘60s too. And you’d be right, but Zappa was leading the pack, which explains the reverence rock royalty of the era had towards Frank and why they made a beeline to his Hollywood hills abode at the time. The difference is that getting creative with editing was intrinsic to Zappa, and in various ways it’s used right across his oeuvre up to the last, posthumously released masterwork, the double-CD Civilization Phase III, where he fused tracks performed by classical players Ensemble Modern with complex Synclavier recordings and added dialogue recorded from within a piano, dating back to his first orchestral album, Lumpy Gravy (1968).

Frank Zappa, like no other major rock musician, thrived on artifice, provoking and joking when so many music fans just wanted soothing with a cool groove and a predictable guitar solo. Right throughout his career, he happily fiddled with recordings after-the-fact. Nothing was sacred: on the live album Roxy & Elsewhere (1974) he overdubbed chipmunk voices on one track and several songs were actually studio creations, and on the even more popular Sheik Yerbouti (1979), a double album of all-new songs, the basic tracks were recorded live but heavily overdubbed and fiddled with. Around this time he came up with a concept he called xenochrony, where he’d extract a guitar solo or other instrumental figure and then place it in a completely different, unrelated context, thereby creating unique rhythms. ‘Rubber Shirt’ on Sheik Yerbouti is one example, while the guitar solos that formed the instrumental core of the Joe’s Garage triple album (1979), for instance, were nearly all xenochronous.

Even towards the end when the cancer was starting to eat away his life force and Zappa was spending time compiling a 12-CD collection of live performances called You Can’t Do That Onstage Anymore, instead of simply releasing whole shows he micro-edited performances together from vastly different stages of his career and even (shock/horror!) folded multiple performances/eras into a single song. This was Zappa’s creative editing technique used as an artistic weapon/expression. It was exactly the way he thought the songs should be conveyed and sequenced and the rigour with which those albums were compiled and edited make them fascinating to listen to 30 years later in a way that the many “whole show” performances released by the Zappa Family Trust posthumously just aren’t.

Even towards the end when the cancer was starting to eat away his life force and Zappa was spending time compiling a 12-CD collection of live performances called You Can’t Do That Onstage Anymore, instead of simply releasing whole shows he micro-edited performances together from vastly different stages of his career and even (shock/horror!) folded multiple performances/eras into a single song. This was Zappa’s creative editing technique used as an artistic weapon/expression. It was exactly the way he thought the songs should be conveyed and sequenced and the rigour with which those albums were compiled and edited make them fascinating to listen to 30 years later in a way that the many “whole show” performances released by the Zappa Family Trust posthumously just aren’t.

For much of his career, Zappa was a road-hog and he put on brilliant, long and hugely entertaining live shows, but he knew that the minute you stamped them into wax it became a different thing, it lost a huge amount of its “being there” allure. He also knew that the recording of music was by its very nature a kind of magician’s box of tricks.

Aside from the recurring motifs and the creative editing, Zappa’s albums are full of remarkable sequencing that actually say almost as much about his music as do the individual tracks. Just as you can’t put Zappa into a music box and he’s one of the most musically eclectic musicians in rock history, his uniqueness (and the consequent brilliance of the records) is intensified by extraordinary sequencing. Take an album like Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970), a compilation of unreleased material recorded by his just-disbanded group, The Mothers Of Invention, during the previous few years. Had this material been sequenced by one of the caretakers of the Zappa vault, it probably wouldn’t have been the utterly brilliant exposition of his outrageous artistry that it is. But as it stands, the sequencing, the way the sections are edited together, and the brilliant variety of material still leaves my jaw on the floor after all these years. (Check out my review of that album here).

Aside from the recurring motifs and the creative editing, Zappa’s albums are full of remarkable sequencing that actually say almost as much about his music as do the individual tracks. Just as you can’t put Zappa into a music box and he’s one of the most musically eclectic musicians in rock history, his uniqueness (and the consequent brilliance of the records) is intensified by extraordinary sequencing. Take an album like Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970), a compilation of unreleased material recorded by his just-disbanded group, The Mothers Of Invention, during the previous few years. Had this material been sequenced by one of the caretakers of the Zappa vault, it probably wouldn’t have been the utterly brilliant exposition of his outrageous artistry that it is. But as it stands, the sequencing, the way the sections are edited together, and the brilliant variety of material still leaves my jaw on the floor after all these years. (Check out my review of that album here).

For those few of you who are still with me in this “2-minute read!” internet reality, I just want to reiterate that while Frank Zappa was an amazing composer, a brilliant guitarist and a very sharp mind, the musical universe he created (partly from the scraps of popular culture) wouldn’t have been what it was without his Conceptual Continuity, meaning everything I’ve talked about here. And that’s why any newbie listener to Frank Zappa music should be wary of starting out with posthumous product.

My recommendation is that you make sure you hear all the proper Zappa albums first, and if possible, listen to each of them over and over until you “get” them, because it’s not something you can just idly absorb or have on in the background. Rich rewards ensue, I promise!

First and foremost, ‘Get A Little’ Frank with these:

Absolutely Free (1967)

We’re Only In It For The Money (1968)

Uncle Meat (1969)

Hot Rats (1969

Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970)

The Grand Wazoo (1972)

Over-Nite Sensation (1973)

One Size Fits All (1975)

Sheik Yerbouti (1979)

Joe’s Garage (1979)

You Are What You Is (1981)

Jazz From Hell (1986)

The Yellow Shark (1993)