GARY STEEL finally finds a book about a group he had stencilled on his pencil case as a high school nerd, and explains why it matters.

It was 1973 and I had to wear scratchy short pants to Hamilton Boys’ High School even in the thick of a fogbound winter. The few friends that I had were into Deep Purple and Uriah Heep and glam rock. They gently chided me for the obscure name that joined the hundreds of others on my star-studded pencil case along with ELP and ELO and Captain Beefheart and The Doors: HENRY COW.

I conveniently forgot this fact for about 50 years because the whole high school experience was just too painful to revisit. When I rushed to leave Hamilton to study journalism in the Capital City, Wellington, I gleefully erased those tortuous high school years from my mental hard drive, along with the few good memories – like my lovely friend Ian Chapman, one of a few mates who had kept me sane. It was Ian who reminded me of my nascent Henry Cow fandom when I finally met him again almost a lifetime later.

Would you like to support our mission to bring intelligence, insight and great writing to entertainment journalism? Help to pay for the coffee that keeps our brains working and fingers typing just for you. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

Henry Cow! What a name for a band! Was I the only kid in New Zealand listening to this obscure shit in 1973? Possibly.

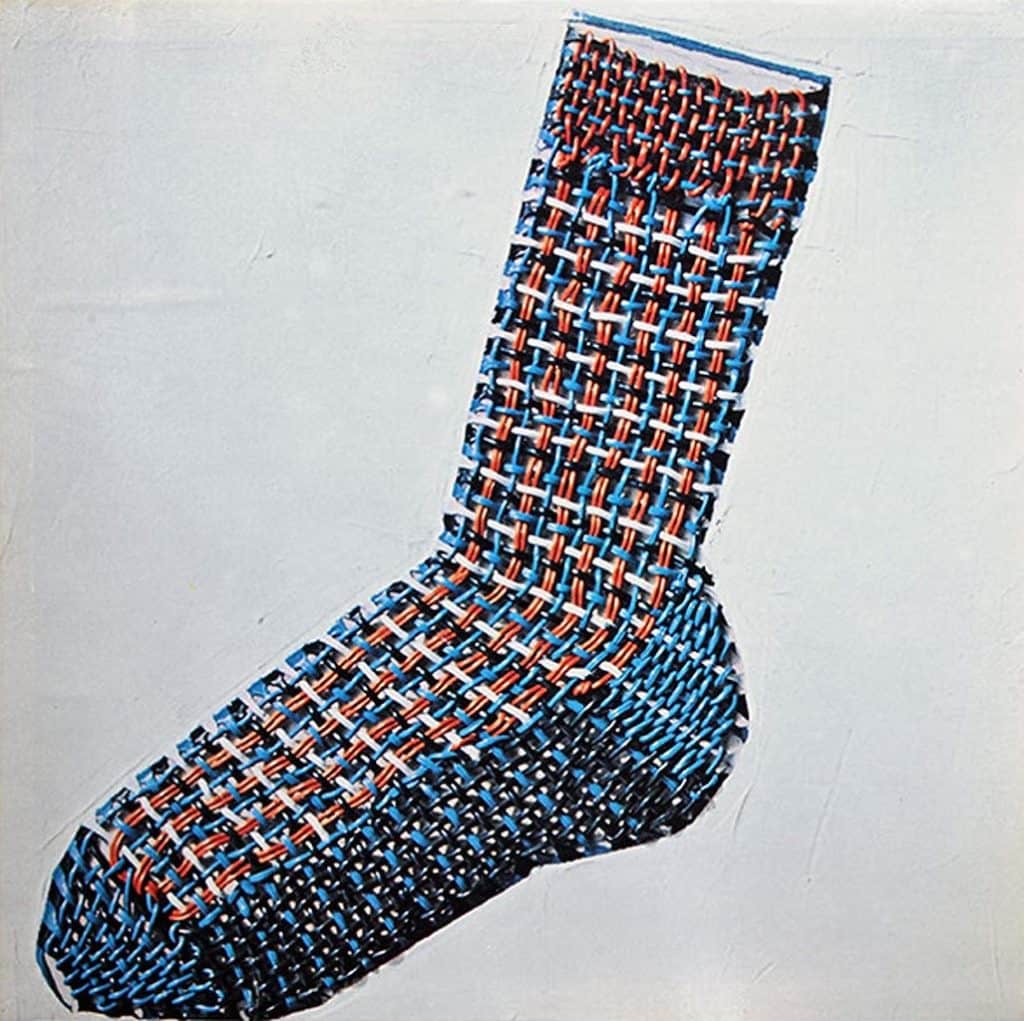

I’d seen a piece in New Musical Express extolling the virtues of this group and its debut album. Called Leg End and (ha-ha) featuring a painted depiction of a sock, the idea of the album appealed much more than the actuality of its music – at least, at first. Emerson Lake & Palmer this was not, and for a few weeks of sporadically intensive listening it perplexed the hell out of me.

It hurt that I’d saved up and spent a fair chunk of my pocket money importing the record from England only to discover that it sounded nothing like Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, the hit record that had bankrolled Richard Branson’s still newish Virgin label. Henry Cow had been signed to the label along with a bunch of hippy freaks like Gong and Faust but their inscrutable sound was much trickier to decipher and decode.

I had expected something progressive (a word that was really being bandied around for the first time about then) and in a sense it was, but it also wasn’t. There were confounding changes of tempo and all manner of discrete virtuosic itches being scratched, but a big chunk of the record was just much too-too.

That is, until the spotty schoolboy played it over and over and over. Unlike Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon, which I’d thrashed for about two weeks and then summarily discarded – feeling that its perfection was somehow numbing and unambitious – or ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery, which came on strong but somehow didn’t quite live up to its dystopian billing – Leg End became more and more intoxicating with repeat plays.

It would become one of my all time top 20 albums, and remains somewhere near the top of my favourites list all these years later. Not only that, but its fundamental musical architecture became a blueprint for much of what I would love subsequently: the combination of intricacy, stealth, actual tunes and improvised wig-outs.

Leg-End was as eccentrically English as a Monty Python skit and there was a certain aroma that came from its recording at the Virgin label’s rural studio, The Manor. But my big takeaway from the album was the idea of collective improvisation as something that could be listened to and enjoyed. To this day, I still find it hard to enjoy completely improvised music, as a rule. For me, there has to be an anchor, or a pulse, or both… something to hold me in suspense, something to act as a bookend to the formlessness. Similarly, I can enjoy the improvised parts of John Coltrane’s rendition of ‘My Favourite Things’ precisely because there’s the promise of a familiar melodic section somewhere ahead.

Henry Cow’s Leg-End worked so brilliantly because those weird sections were never going to stretch on for infinity. Sooner or later, their quirky compositions always return. But within the safety of that format, those improvisations were fabulous, and what I discovered about them was that if you listen to an improvisation (which only happens once in real time) a hundred times it becomes a composition in your head.

In the case of Henry Cow, they were blessed with uniformly great instrumentalists, and although they were incredibly nimble players, it was more that the intent with which they played came through. Fred Frith, for instance, could have been a conventional “guitar hero”, but kept the lid on any unnecessary bouts of widdly. In addition, there was something charming about Frith’s compositions – a characteristic that came to full fruition some years later on his Gravity album. Keyboardist Tim Hodgkinson’s compositions were, by contrast, serious and analytical and seemed to give the group a sense of purpose. Bassist John Greaves brought with him a certain style and levity while saxophonist Geoff Leigh gave the group a hint of jazz. Chris Cutler was (and is) simply one of the most extraordinary and exploratory drummers/percussionists on the planet. In other words, there simply wasn’t a weak point in this group, and despite Leg End being their first foray in the studio, it’s far from a tentative beginning.

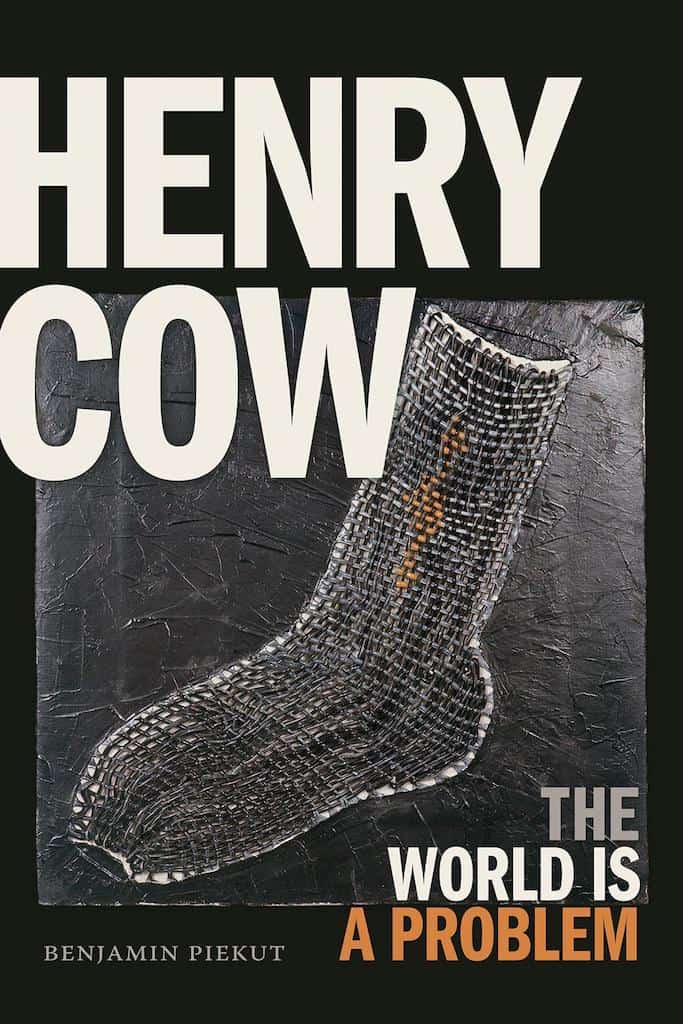

I followed Henry Cow through their subsequent albums and into their post-Cow group Art Bears and subsequent solo, collaborative and group work, but always felt that there was a story here that needed telling. I knew and loved their music but little about how they came to be, who they really were and how their time unfolded. Blow me over with a feather duster, in 2019 I got wind of a 500-page tome, Henry Cow: The World Is A Problem by Benjamin Piekut (Duke University Press). Of course, I had to have it. But then it sat beside my bed for a year. Children, life and everything got in the way. And then my eyes packed up.

A couple of months back, I finally made my way slowly through the dense prose of this 500-page academic work. The 27-page introduction was almost enough to knock my enthusiasm for the subject, and the book, on the head. It barely mentioned the group and got bogged down in definitions and discussion about stuff that might have been kept to an academic dissertation on the book rather than a part of the actual book. Piekut seems to have felt that to give the group 21st century relevance he had to dissect things from an almost post #me-too, cancel culture perspective.

When the book – and the group’s story – begins in earnest, however, it’s a compelling read, especially for anyone struggling to understand where these musicians came from, how an obscure British band could struggle on for so many years (and to what purpose), and to get a birds-eye view of a particular time in UK music history. The collective intentions of the group to change the face of popular music make up the core of the story. Their idea – and one that many believed in for a time in the 1970s, including myself – was that it should be possible to create a revolutionary new music that took some of its cues from popular music but eschewed all of its seedier characteristics. Deeply socialist, the group rejected academic elitism on the one hand while also rejecting anything remotely consumerist. Given that they spent much of their time biting the hand that fed it, I’m even more amazed at the conviction of Henry Cow’s members and the relative longevity of the group.

Through its Virgin label connection Henry Cow was often labelled “progressive rock” and members contributed to records and shows by the likes of Brian Eno, Mike Oldfield and Robert Wyatt, whom they greatly admired. But really, they were way out on the left field of “rock”, unpopular music that shared more with the radical sonic frontiers of Faust or the very strange French group Magma. And although they’re often aligned with the Canterbury scene (Soft Machine, Caravan) they more or less came from Cambridge (UK university town, not the leafy New Zealand village!) and had their roots in everything from blues to folk to theatre. Frith may have been influenced by the blues, but his intellectual refabrication of the form turned it into something completely different. Cutler may have had a soft spot for The Who, but any cock rock moments were turned completely on their head in the Henry Cow universe.

Piekut has spent years talking to former members and associates and accordingly, gets right inside the various struggles the group went through. Sometimes, his academic approach and lack of journalistic editing skills make for too much needless detail, including long transcripts of discussions/arguments the group had in its often problematic journey. While it’s instructive to get a sense of just how serious and pedantic things could be in the Henry Cow camp, these extracts sometimes bog down the flow of the story itself.

He also spends a lot of time delving into the personal and sexual politics of the individual members. Was this really necessary? The fact that Fred Frith was guilty of sleeping around a bit when he was in his early 20s is hardly revelatory about any young man. I get that his aim was to construct a narrative that explained the issues around a bunch of musicians trying to construct an entirely new, equitable universe while conforming to macho dominance typical of the time. But surely that was the landscape back then. Only so many barriers can be broken down at one time and the world can’t be changed overnight. The increasingly fraught socio-political differences in the band partly explain its dissolution in ’78, but I can think of a couple of more plausible ones: 1) Without the support of a “major” record label after 1976 the group struggled financially and had to stay on the road much of the time just to keep its members fed, and 2) The road goes on forever and eventually, it’s a sure thing that at least some members will get tired of sleeping on couches and begging for food money when gigs don’t eventuate in foreign towns. Remember, this was a time just before the explosion of “indie” labels and the cool cultural cache that came with them.

Still, for a longtime fan, Piekut’s interviews are something of a revelation, as is his detailed deconstruction/explanation of the music itself. He goes so far as to provide his own “dots on paper” representations of extracts from some of the pieces. Weirdly, this displays a level of dedication that seems somewhat at odds with Piekut’s own view of the group and its music. He’s clearly a fan but seldom comes out with overt praise of the group’s oeuvre, more often instead finding reasons to point out flaws and failures on the group’s recordings. Piekut finds Leg End wanting in all sorts of ways, as do the former members of the group. It’s common for musicians to dislike their early work because that’s where they’re still learning how to deal with producers and engineers and overdubbing. Listeners removed from the process just hear great music. But the author somewhat fails to identify the genius of that album while reflecting positively on later work that – to these ears at least – sometimes comes across as laboured and awkward.

Piekut is obviously a big fan of improvised music and he leaves many of his most effusive comments to experimental passages recorded at gigs and included in the 2006 Henry Cow Box. Fair enough, but if Henry Cow were simply a band whose work consisted only of sprawling improvs, I would never have connected with their music.

It’s also somewhat tragic that Piekut didn’t see fit to conclude the book with the immediate post-Henry Cow activities of the members. As there’s unlikely to be a book – in my lifetime at least – about the Art Bears or The Work or oboist Lindsay Cooper’s Rags, it seems like a missed opportunity to point out that while the world of Henry Cow was a problem (ha-ha), in the post-punk era the individual members came into their own with some incredible projects that capitalised artistically on the work they had undertaken in the “collective”.

While I’m pointing out its flaws, it’s also worth noting that for all its dense analytics, The World Is A Problem doesn’t tell the humble fan (like myself) some of the stuff we really want to know. For instance, why was In Praise Of Learning recorded at such low volume, and why haven’t any of the reissues boosted the volume or fattened the mix? And what’s the story behind the radical remixes of several of the albums done by Tim Hodgkinson in the early ‘90s?

What the book does do well is to explain – via long passages on the “Krautrock” group Faust and Henry Cow collaborators Slapp Happy – the turbulent flux and mutation out there on the fringes of rock in the ‘70s. It was a time when “rock” still held some promise as a revolutionary artform that could be inclusive of just about any music form without simply aping styles. And, as the book points out, groups like Faust created an entirely new musical language in the recording studio. Unfortunately, Henry Cow and the R.I.O. movement they inspired in Europe (as well as many of the artists on Cutler’s Recommended record label) would remain a beacon of adventuresome contemporary music while, in the ‘80s, popular music fractured into competing demographics.

There’s also entertainment value to be had in reading of the group’s unsatisfactory tours with Faust and especially Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band (renamed by the group as “the Tragic Band” on the occasion of Don Van Vliet’s decision to hire session musicians to replace his real band).

For some reason, it never concerned me that no one else knew or cared about Henry Cow at high school. Music was never a popularity contest to me, or a way to align myself to others or win friends or whatever. Over the years, I’m delighted to report that I have met a few individuals who express an appreciation of the group. It’s probably true that a lot of Henry Cow’s music is flawed, but that it also contained elements of towering greatness. It’s probably also true that a lot of the music I love is flawed. Perfection gets boring very quickly, but striving towards greatness… that’s something special. Life’s failures are often also great achievements in retrospect. I applaud Benjamin Piekut for having undertaken this massive project. It’s an achievement, but it’s also flawed. I thought that The World Is A Problem might be the final word on Henry Cow, but not… there’s still a conversation to be had.