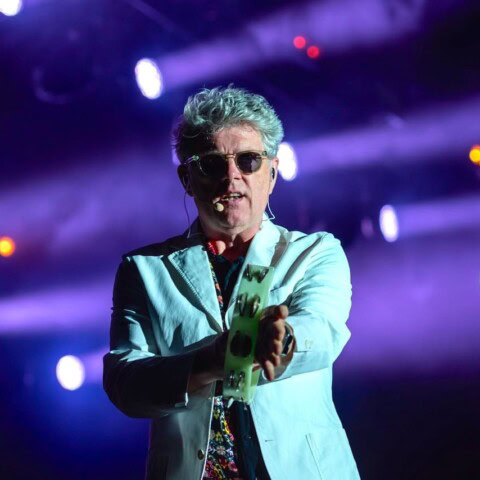

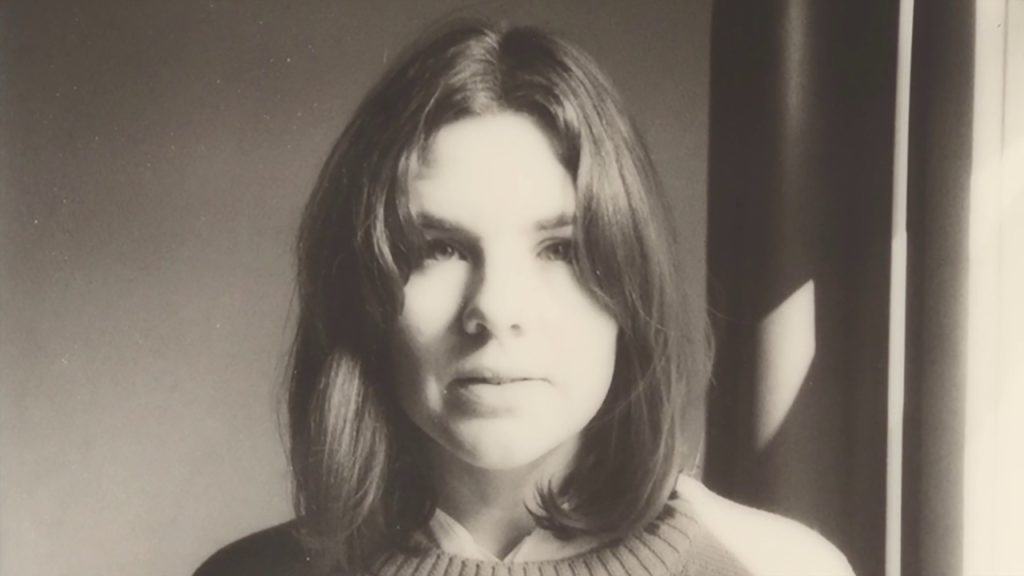

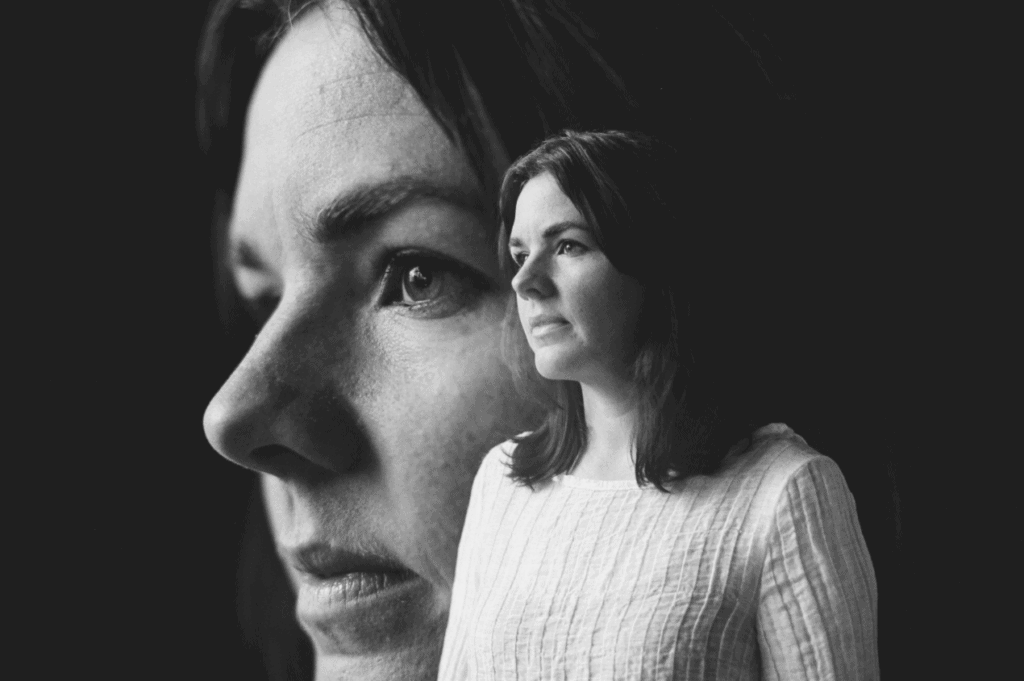

In the latest instalment of Witchdoctor’s UNEXPURGATED series, we find RICHARD BETTS deep in conversation with Tiny Ruins singer/player Hollie Fullbrook.

I interviewed Hollie Fullbrook in 2018 for the NZ Herald ahead of a concert she was about to play with Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra. The show was part of the celebrations commemorating 125 years of Women’s Suffrage, and featured music by women composers and performers, as well as non-musical appearances by other top-of-their-game females including then poet laureate Selina Tusitala Marsh and microbiologist Siouxsie Wiles.

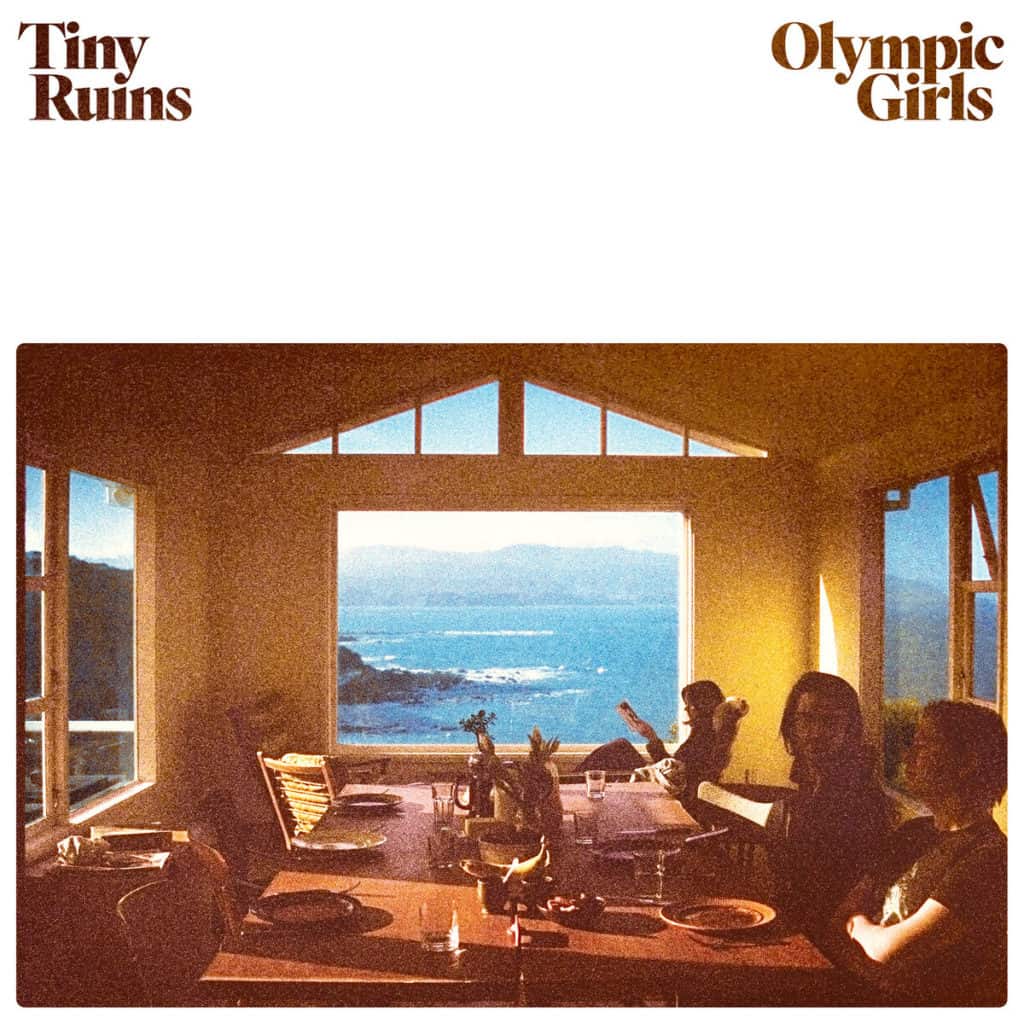

When Fullbrook and I spoke, Tiny Ruins had yet to release their third album, Olympic Girls, though the single of the same name had recently emerged. Fullbrook proved a great interviewee. During our 45-minute chat she was thoughtful and witty and self-deprecating, but the nature of newspapers meant that only a fraction of what she said appeared in print, so most of the interview is reproduced here for the first time.

Richard Betts – The new single, ‘Olympic Girls’, has the vocal way up front, it’s less misty than your vocals have been in the past. There’s also a lot going on musically in that song: swirling psychedelia that reminds me of Love’s Forever Changes album, there’s hi-life-style guitars, some of the imagery is even like Jacques Brel. Is this your new direction?

Hollie Fullbrook – I wouldn’t call it a new direction. I feel we’ve been going in that direction for quite a few years, even since [Tiny Ruins’s 2014 breakthrough album] Brightly Painted One. There were songs on that album I knew was the direction of this one and the songs have been written over the last three or four years, so for me, it feels like a gradual shift to a more band sound, but I understand why other people might see it as a new sound. For me, it feels like we’ve been going that way for quite a long time.

Richard – Is it indicative of the forthcoming album?

Hollie – Yes. Have you listened to [single] ‘How Much’? I would say those songs are kind of sides of a coin, and some of the songs are more pop, like ‘How Much’, and some have more of a folk bedrock, like ‘Olympic Girls’. There are definitely songs on the album that are more reminiscent of the more pared-back Tiny Ruins sound of [2011 debut album] Some Were Meant For Sea. There are a couple on there that are like that, but for the most part it’s more of a full sound, either in the more pop direction or in a more indie-folk way, if you want to put it into a category.

Richard – I was listening to an interview you did on [US public radio station] NPR.

Hollie – [laughs, regretfully]

Richard: Is that a bad laugh?

Hollie – Yep.

Richard – The lyrics of ‘Olympic Girls’ refer to the real-life event of a bus trip, where you shared a ride with a guy called Courtenay who’d been released from prison that day. I would never have guessed what it referred to, but knowing that story it becomes quite clear. Did you stay in touch with Courtenay at all?

Hollie – No, I lost his number. But you know, it was hard knowing whether to tell that story or not, because I’m really reluctant to change anyone’s own perceptions of songs. There are so many layers in a song, it definitely isn’t just about that story. Obviously, telling the story to NPR, they wanted one or two minutes, and to tell a really complicated, long story in that amount of time was so difficult, so I ummed and ahhed about revealing that inspiration for the song. But it was such a specific story and I talked to my bandmates about it and they were like, ‘We think it adds to the song, rather than takes it away for people.’ But I still have mixed feelings about whether to talk about it or not, because all songs have many layers to them, there’s not one thing they’re about. But certainly, for Courtenay, I did always think about that experience and I don’t know what happened to him. This was a time before Facebook and phones and everything.

Richard – From your brief time together, what do you think he’d say if he knew you’d written a song about that encounter?

Hollie – He loved music. We talked a lot about music. He was very critical of my tastes, of course [laughs]. I think he would be thrilled, actually. I don’t know whether he’d remember that experience because it was probably a day that was extremely full-on for him, being reunited with his family and everything he’d been through. He wasn’t that much older than me and he’d been in [prison] for three years, so it was a big thing to be coming out. I think he would have liked the fact there was a song written about it. But you never know, he might not remember it at all.

Richard – I think ‘Olympic Girls’ is a really good example of one of the things I like most about your writing. You can have a very specific idea, but you throw in something inexact, and yet it remains beautifully expressive. Another example might be ‘Me At The Museum, You In The Wintergardens’ [from Brightly Painted One], which seems a very straightforward song but you still have things like this amazing image, ‘buttery and brief’. I don’t know what it meant to you, but it’s expressive enough for me to draw something from it.

Hollie – Yes, and for me, it is something very specific. The joy I get out of songwriting is that it’s about referencing something specific to my own life that means something to me, and it’s almost like a secret. I am reluctant to give away the secrets but I understand the wanting to know. My friends and family often ask me about the lyrics and sometimes they get a little bit out of me. That’s what happened with this NPR story, my bandmates got it out of me. What can I say? I want it to be other people’s. I want it to have their own telling and imagination, like when you read a book your imagination is half of the story. That’s kind of what I want my songs to be like. It’s a bit of both; I understand I have to compromise for these nosy people.

Richard – Another phrase is ‘leotard twirls’ from ‘Olympic Girls’. I love that image. It encapsulates something but it’s inexact.

Hollie – Yeah, I was really happy with that line when I wrote it. I especially liked the ‘frosted’ [‘frosted sheen of leotard twirls’], because I feel like the frosted is really how I feel about leotards, they often have that semi-sheen. I was happy with that line.

Richard – Do your lyrics start as poetry?

Hollie – No, I would say they start out as more automatic writing, vague observations and sifting through memories and images in quite a sprawling way. But then often one line will stand out and that might become a chorus line, or the key image. If I look over writing I’ve done in notebooks or whatever, I’ll know it when I see the line that’s the one that stands out from the rest. And then it does become more about putting lines in order like a poem. But it’s always with the knowledge it’s a song, so you’re thinking of verses rather than stanzas or whatever. And you’re thinking of the rhythm of the lines a lot more than maybe if you’re thinking about a poem.

Richard – Have you ever performed as Tiny Ruins with an orchestra?

Hollie – No. [Laughs].

Richard – There was some trepidation in your response then.

Hollie – Well, I almost ended up being in an orchestra. That was what everyone expected me to do after high school, be a professional cello player, which is quite bizarre to think about now. So it was almost my career. I did a mentorship with the NZSO and sat in with them and everything. The classical world was not for me, but here we are, meeting again [laughs]. I love it really, I’m really excited. There’s something special about the machinery of a moving orchestra, and how they’re all part of this whole and not really standing out. I love that idea. I don’t know how it will feel to be on stage playing my song with them, it’s insane. I’m excited just thinking about it.

Richard – I wanted to ask about cello. You were obviously pretty good.

Hollie – Well, I was. I was good once, but it’s very easy to get rusty.

Richard – You played a bit on Brightly Painted One. Are you playing on the new album?

Hollie – I play all the cello on the new album, there’s quite a bit but I’m so rusty that what I do with cello now in recordings is more textural, droney kind of stuff. It makes a big difference to a recording, it’s such an evocative instrument. It needs to be used quite sparingly, but I love arranging the string parts.

Richard – You were in youth orchestras?

Hollie – I was in the Auckland Youth Orchestra, I was in Avondale College orchestra and chamber orchestra, piano trio. When I was in high school classical music was really the system I was within, even though I longed to be part of the jazz groups and the more exciting band stuff. But I played cello and all my friends were also part of the music department and that got me through high school, really. I wasn’t great, I was a pretty stock-standard cellist, but I did all the grades. My music teachers really believed in me. They knew I played guitar and sang a little bit and wrote these funny little songs even then, but what they really pushed me towards was going to music school in Auckland and being a cellist.

Richard – This concert very consciously places you in a lineage of important composers, and specifically important women composers. Is that a weird feeling or not something you’ve thought about? Or do you think, ‘No, I deserve to be there’?

Hollie – As soon as they asked me to be part of it, it was like, ‘wow’. It’s a huge honour. To be a songwriter next to actual, proper composers. I don’t feel like we’re in the same ballpark, quite frankly. But I appreciate being asked to be part of it.

Richard – You’ve recently played with The Chills and you made the EP Hurtling Through with Hamish Kilgour of The Clean. Was Flying Nun influential on you as a young person?

Hollie – No, I can’t say they were when I was growing up. My family are British and we moved here when I was 10, in the mid-’90s. Mum and dad would buy Bic Runga and Neil Finn, a lot of New Zealand music to try and give us a bit of local knowledge when we were kids, but they didn’t know about Flying Nun. I probably got them on to it. I know I had a Chills album when I was at university, probably when I was about 19 or 20, because an ex-boyfriend liked The Chills. It wasn’t really until I met Hamish that I really got into the back catalogue. Toy Love was the one I connected to early on. And then working with Robert Scott. I love The Bats, and Robert’s songwriting. That was probably 2013, something like that. From my mid-20s on I guess I became aware of that history that I wasn’t raised on.

Richard – What did Hamish Kilgour learn from you?

Hollie – He probably learnt how to do touring in a DIY way. That’s a joke… He was quite shocked at how DIY I am. Coming from a punk background he fancies himself as the classic DIY but musicians now have to be so much more almost punk, with that mentality, than successful bands from the ’80s had to. They were supported in lots of different ways, more than we are.

Having said that, we toured around Europe together for three and a half weeks, just the two of us in a car, me driving. It was a lot of fun but he was tired by the end. He was like, ‘This is hard work! No tour manager, no driver’. I love him to bits, we have so much fun together and have a weird, similar sense of humour. He is one of those people who is really open and willing to learn from others. He’s got a kind of childlike sensibility towards the world, which I think I share with him. Everything is kind of an adventure. It’s all about music, really. I’ve learnt a lot from him. The way he operates is so spontaneous. The way we ended up working together was literally that he turned up. My very first gig in New York, and he just got on the stage and played drums along with me without any discussion.

Richard – That sounds stressful.

Hollie – You know what? It was actually so much fun. We had loosely planned for it. We’d have to start each song, we’d get the tempo right, the audience must have been really confused but it was so magical, I can’t explain it any other way. For me to play with someone who is completely going by feel and intuition. My band are like that as well, we just operate in a really different way. I love that about Hamish. It can be really ramshackle, it’s not the tightest performance of a song but it’s so present, you’re both listening to each other, trying to create something for that moment. That’s not something many musicians are comfortable doing.

Richard – Why has the new album taken so long? It’s four years since Brightly Painted One.

Hollie – It’s taken a little while. We recorded it quite differently. We didn’t record it in a condensed window of time like all my other stuff, we recorded it gradually. As I wrote song after song we’d get together and workshop the song for a couple of days and then record it. That took a year and a half of recording when we were all available because we all have other jobs.

Tom [Healy] the producer, who’s also in the band, is really sought after, everyone wants to record with him. And I didn’t want to rush this album. I knew that this was a really important album to me just from the three or four songs I had already written. I knew that I needed to not rush it, focus on the quality of the songs and be really sure I’d done justice to three or four songs I knew were really good. I don’t know, why do things take so long?

Richard – Life happens.

Hollie – Life happens, yeah, and that’s exactly what did happen.

Richard – In 2012 you told Guy Somerset of The Listener, ‘I definitely don’t feel like I’ve made it in any sense of the word.’ How do you feel now?

Hollie – Kind of similar. I know from outside musicians’ and artists’ lives, you see these moments of them, when they release things. But when you’re in it…

What I know is I’ve managed to keep going and I’ve managed to do a few things I’m really quite proud of. Like I’ve managed to almost pay off my student loan. But to really make it for me would be to be living in my own house and having a family and having an established career where I knew I could do a tour and it would be successful. I don’t feel I’m at that point. It’s a tough job. I always knew it would be.

There’s a lot to be grateful for, but most artists you think are doing really well are similar to me, I think. Ranting [laughs], definitely having a part-time job on the side. That’s the reality of being a musician today, and you have this patchwork quilt thing going on where you do a tour, you release something and that keeps you going for a bit longer. You have some other job and other things going on. It’s really fun working for yourself and being your own boss but there’s a lot of work involved. You’re running a business. I hate putting it like that, but I don’t have the luxury to be swanning around drinking champagne.

Richard – What are you doing for part-time work?

Hollie – I have a little admin job.

Richard – Is that grounding for you?

Hollie – I’ve always had very grounding jobs. I’ve worked in hospitality for many years, I’ve done nannying. Everything you can imagine, I’ve probably had a job in it.

Richard – What’s it like? One day you’re playing to a packed house in an East Village bar and the next you’re back at a desk in your job in New Zealand…

Hollie – Filling the dishwasher and picking up people’s mugs. It’s fine. I don’t believe really in the trappings. I do love decadence but I’m not really a decadent person. I like feeling busy and I do like knowing what the world really is, and having a job with regular people is really important as a songwriter.

If you don’t know what’s going on and how people think and talk, if you become disconnected from reality then you’re not going to be a songwriter people can relate to. I always loved that when I worked in cafes and restaurants; I loved the feeling of seeing a real slice of life. In Wellington, I worked in a whole bunch of places where it was like, ‘Okay! This is people!’