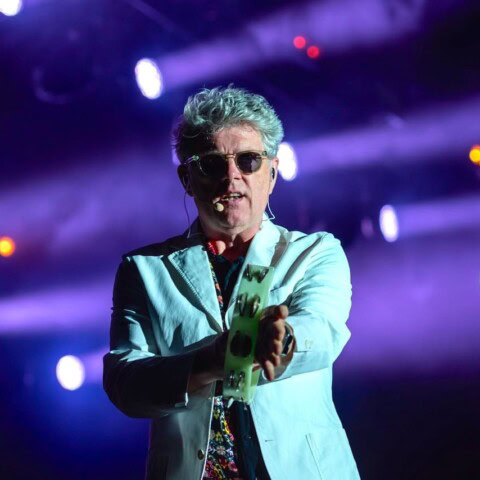

Fifty years ago Tim Buckley released an album that killed his career. Five years later he really was dead. GARY STEEL on Starsailor.

It was a line that a 14-year-old boy could never quite forget: a female rock scribe called Chrissie Hynde describing the voice of singer-songwriter Tim Buckley. If a human voice could bring her to orgasm, she wrote, Buckley’s would have that distinction. The year was 1974 and it was a few years before Hynde moved from half-hearted rock journalism to fully-fledged rock and roll stardom in The Pretenders.

The publication was New Musical Express (NME) and I still have the cutting, somewhere. I remember that they’d fucked up the paragraphs in the printing process and that a few were missing and wrongly transposed. I remember the ardour with which she spoke of Tim Buckley’s talent and made a mental note to endeavour to get hold of one of his albums.

Would you like to support our mission to bring intelligence, insight and great writing to entertainment journalism? Help to pay for the coffee that keeps our brains working and fingers typing just for you. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

It turned out that the story/interview with Buckley would be the first and last thing I saw on him until his death by heroin a year later. By then, I was a frequent customer of an American vendor of “cut-out” (deleted) albums and whenever my earnings from the paper round were enough, I’d send off for another box of cheap vinyl, most of which would arrive four months later, slightly warped but still playable.

I was 15 when a package containing two budget-priced Tim Buckley albums – Sefronia and Starsailor – arrived at customs in Hamilton. I had to traipse downtown from suburbia to go through the boring rigmarole of collecting my records from old men in uniforms who seemed highly suspicious and probably, in retrospect, suspected hidden drugs. I hurried back to my teenage room and my modest portable record player and dropped the needle on Starsailor, because it came out in 1970 and Sefronia came out in ’73 and that was the right order to play them in.

I fucking hated it. Everything was wrong with this record. For a start, there was none of the production trickery that made the early 1970s such a sonically distinctive time. The instruments were recorded in such a way as to make them sound incredibly stark and dry. It was a musical bone-yard. And then there was Buckley, whose yelping and caterwauling and yodelling and off-notes made me feel embarrassed.

And then I listened to Sefronia. What a contrast! Just three years later and this was about as middle-of-the-road as my listening tastes ever went. There was a sentimental Tom Waits song and a beautiful rendition of the Fred Neil song, ‘Dolphins’, and the alluring two-part title tune that mixed in a lurid colonial-era saga about a love affair with a slave that was shockingly sexual, with lines like “let me sip weakness from your dark nipples”. Yowza!

Sefronia – an average album with a few really great songs and some superlative vocal performances – was a kind of Buckley taster for me, and was all the encouragement I needed to try Starsailor again. If he could indeed sing like an angel, surely that weird record must have something going for it. And sure enough, after another couple of run-throughs, I couldn’t stop playing the record.

At 15, I’d already tasted “free jazz” and the avant-garde fringes of rock and some pretty far out “global” music as well as extreme modern classical, but Starsailor existed in its own universe. Tim Buckley’s early records were in thrall to the boho spirit of Fred Neil, but his roving, adventuresome character ensured that they were utterly distinctive, wayward and original. In the same way, Starsailor took inspiration from the jazz extemporisations of Coltrane and his cronies and translated them to the human voice.

But even as I write those lines, I can see the error of my ways, because it’s just not as simple as that. The easiest way of explaining it is to delve a little into Buckley’s astonishing musical evolution over the previous five studio albums. Just 19 when Elektra released his self-titled debut in 1966, Buckley’s sound at this time fit easily in with his label’s folk-rock aesthetic and wouldn’t have seemed out of place next to a band like The Byrds. The most distinctive thing about it was Buckley’s voice, a tenor that was capable of giving the listener goose-bumps. Like Roy Orbison before him, Buckley was the owner of a freak vocal apparatus that could seemingly swoop up to counter tenor-like frequencies but also plummet down to a bass-boosted midrange that few tenors countenanced. Add to this his interest in experimenting with that voice and despite the tentative nature of that first album the beginnings of an audacious talent are easy to identify.

From there-on-in it would be a wild ride through Goodbye & Hello (’67), Happy Sad (’69), Blue Afternoon (’69) and Lorca (’70). Goodbye & Hello would take Buckley’s exploration of the folk-rock sound about as far as it could go, and with the help of producer Jerry Yester, he fashioned masterpieces like the epic title track and gorgeous ballads like ‘Once I Was’ and ‘Morning Glory’, a song that would become a minor hit for Linda Ronstadt. At this point, everything indicated that Buckley would become a major force in the new hippy music revolution.

But then he took a left turn and made Happy Sad. From then on, Buckley would annihilate his career by taking left turn after left turn with each successive album until with Starsailor he found himself without an audience at all. Listening to Happy Sad now it seems odd that a record like this might confuse fans, but the difference between Goodbye & Hello and Happy Sad is stark. Buckley had discovered jazz, hired a jazz dude to play vibraphone and another (an African-American to boot) to play congas, and the whole record was like a moody dream. It was Tim Buckley’s Astral Weeks, and it was gorgeous. Because the songs are mostly long and rambling there’s ample time for vocal extemporisation, and his second epic, ‘Love From Room 109 At The Islander (On Pacific Coast Highway)’ burrows deep down into an immersive existential sensuality that’s uniquely Buckley territory.

Despite its vastly different stylistic tendencies, Happy Sad was rather approachable and friendly. The same could be said for its follow-up, Blue Afternoon, which contained some of Buckley’s most ravishing tunes and beautiful vocal performances. This close-miked, extremely sensual, intimate and introspective album would play nicely next to English folk singer-songwriter Nick Drake, except that where Drake is like a ghost on his own records Buckley inhabits his as a larger-than-life entity. It’s another classic.

Lorca, however, took that introspection to extremities that, in retrospect, must have turned off many of the fans who had weathered the extreme changes thus far. His fourth album in less than two years was primarily riff-based and mysterious and gave him the space to improvise vocally, but more on the lower end of his range. It’s the kind of album that seems to be suspended in some parallel existence where it’s always 3am. The imagery is all interior and the sexual imagery on songs like ‘Driftin’’ is so rich that it’s like having a bedside view.

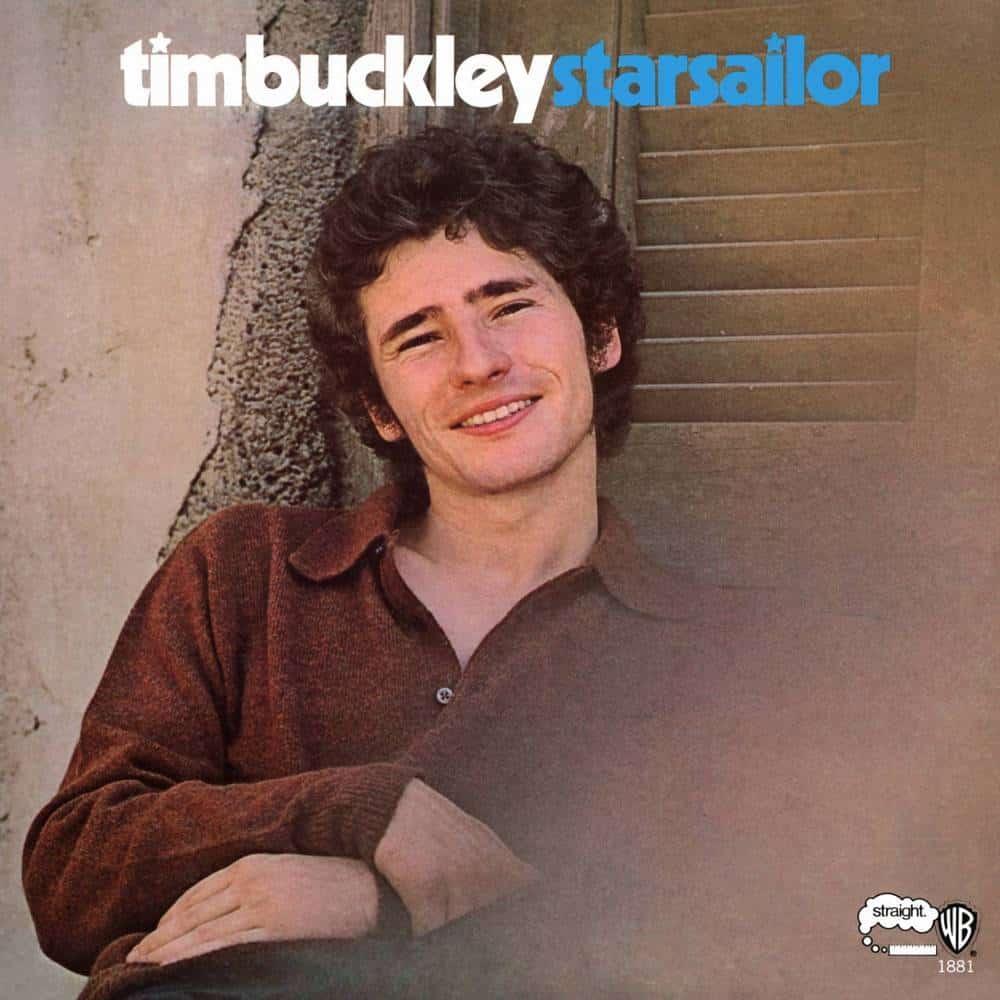

For all its richness and its undeniable strengths, Lorca is also a deeply flawed experiment. It’s like a luminescent meteor orbiting the wild planet that is its incredible followup, Starsailor. It’s incredibly rare in what used to be referred to as “rock’s rich tapestry” to come across a recording that is so much its own thing that it relates to little else. Instead of the adorned covers of previous Buckley albums, Starsailor features a photograph of the artist looking directly into the camera and smiling. It’s a beautiful picture of a beautiful man, honest, untouched. The back cover is mostly plain white with a lot of space and a simple list of the songs and lineup down the left side. I can’t imagine it any other way. It’s saying “this is me, here I am, take it or leave it.”

Sadly, few took up the offer. In 1970, there just wasn’t a niche for the “outsider” artist, especially one who had started so conventionally. There was no template for the kind of rapid evolution Buckley had been through and the kind of stripped-back, extremely raw and profoundly emotionally naked compositions and performances featured throughout were simply unprecedented.

There were two wonderful, relatively conventional songs on the record: ‘Moulin Rouge’ was a romantic ballad mostly sung in French, and it gave a glimpse of the remarkable versatility of his voice in a strikingly less extreme context. ‘Song To The Siren’ was an earlier song that had (improbably) featured on an episode of The Monkees’ TV show in 1967, but which would remain obscure until the Cocteau Twins (as This Mortal Coil) recorded their version of it in the 1980s, sparking the first flickers of interest in Buckley more than 10 years after his premature death.

That such a remarkable song lay hidden on one of the most obscure and unloved albums of all time seems like a rich irony. Surrounding these two songs were various levels of sonic and emotional extremity. The title track is a case in point. ‘Starsailor’ contained what would now be called an ‘ambient’ backing of sheets of sound that are essentially Buckley’s voice extensively overdubbed into shrieking falsetto choirs. Over that scary celestial backing he intones poet (and frequent lyricist) Larry Beckett’s words, which include the prophetic line: “Oblivion carries me on his shoulder”.

On the out-of-print late ‘80s Enigma label CD reissue, the lyrics include what purport to be handwritten ‘Composer’s Notes’ that explain this extraordinary piece: “Harmonic structure: A set of horizontal vocal lines is improvised in at least three ranges, the vertical effect of which is atonal tone clusters and arhythmical counterpoint. Performance: The written melody is to be sung, after which the lines of lyric are to be reordered at will and sung to improvised melody, taking advantage of the opportunity for quartertones, third note lengths and flexible tempo.” I would never have imagined the piece was as thought-through as this, but ‘Starsailor’ is at great variance to the rest of the album, in which Buckley tends to begin with a vocal preamble before the band launch into insistent riffing, which then inspires the artist to the heights of abandon.

With largely self-written lyrics, although stylistically it’s a world away from Buckley’s next album, the porn-funk classic Greetings From LA, Starsailor is electric with sexual imagery, and this fits perfectly the surging, snapping, screaming grooves his musicians establish in each piece.

Perhaps the easiest entry to this world is the last song, ‘Down By The Borderline’, which on reflection provides an entry point to the Mexican-obsessed imagery of his final three funk-oriented albums. “When a little girl passes by/You can smell the way she walks”, he enthuses, as the riffing gathers pace and his voice takes flight into mad ululations and speaking in tongues. With Buzz Gardner’s crazed trumpet blasting away and its irrepressible groove, it’s almost a relief after the intensity of the previous songs.

I could write an essay about each and every song on Starsailor, but will resist the urge. Suffice to say that this is an album saturated in transcendence, one that’s all about breaking on through from the mundane to something that’s ecstasy-laden. It’s Buckley’s main theme, really, losing oneself completely in the act of sexual union, becoming somehow other in that moment. Over and over again in Buckley’s songs he explores a notion of sexuality that today the Millennials might call an attempt at escape from the binary world. Don’t get me wrong, his vocabulary is tied to the era in which he existed, but Buckley seems obsessed with the notion of sexuality being all-consuming, beyond the man/woman paradigm, beyond the bodily prisons in which we’re trapped. It surprises me that in all the words that have been written about Buckley, no one to my knowledge has discussed this feature of his writing.

Recommending just one highlight from Starsailor would be impossible. Though there is a certain uniformity to the structure of songs like ‘Jungle Fire’ and ‘Monterey’, each is also wonderfully self-contained. But it’s an intense experience; one which reaches a crescendo with ‘Starsailor’ and the almost apocalyptic propulsion of ‘The Healing Festival’.

I don’t listen to Starsailor much anymore, but it’s a rare pleasure kept for when nothing else will do. As a teenager and young adult, it was the record I would put on (really fucking loud) to blow away all my psychic detritus. Instead of putting on a Joy Division album when I was low, I would use Starsailor to blow away the blues with the sheer gale force of its vision.

Sadly, the world wasn’t ready for it. The album tanked, and the Starsailor tour played to near-empty houses. It was impossible for Buckley’s career to regain its momentum. I’ve got a tape somewhere of the singer playing support to Frank Zappa and the Mothers in the early ‘70s and the audience is booing him. The last three albums (Greetings From LA from ’72, Sefronia from ’73 and Look At The Fool from ’74) had some amazing songs but still seem puzzling in their outright attempt at commercial funk.

Tim Buckley died from a heroin overdose in June 1975. His son Jeff, who he only met once (Tim’s song ‘Dream Letter’ is about him) came to prominence in the mid-‘90s after being “discovered” at a celebration of his father’s music. ‘Dream Brother’ on his album Grace is about his dad. He died in a drowning accident in 1997.

A first-rate article about the full scope of Tim’s amazing creatives journey, with special emphasis on Starsailor (which Tim regarded as his masterpiece. Kudos to music journalist Gary Steel. Great insight; great honesty; terrific and accurate language. Way to go, Gary. You done good!