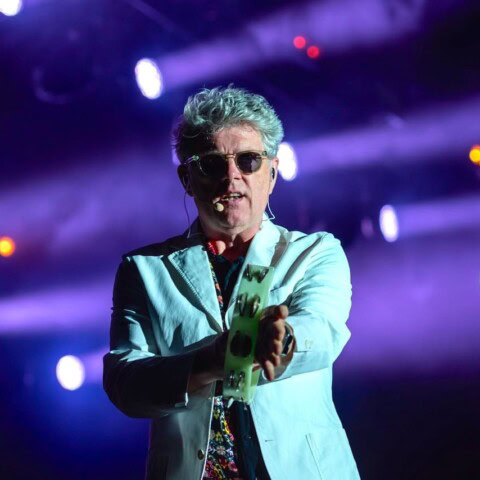

The Phoenix Foundation have just released their first album in five years. RICHARD BETTS interviews singer Samuel Flynn Scott.

I interviewed Samuel Flynn Scott for the NZ Herald in July 2018, just as The Phoenix Foundation were about to perform with the NZSO. In a 20-year career, it was the first time the band had ever played with an orchestra, and Scott was both anxious and excited by the prospect. To celebrate the new album, Friend Ship, Witchdoctor runs this interview as part of its UNEXPURGATED series.

Richard Betts – The concert is being advertised as a 20th-anniversary gig, is that right?

Samuel Flynn Scott – It’s 20 years since we decided we were The Phoenix Foundation and when we started taking the music more seriously. But me and Conrad [Wedde] and Luke [Buda] have been making music together since we were 14, so that’s a little longer than 20 years.

Would you like to support our mission to bring intelligence, insight and great writing to entertainment journalism? Help to pay for the coffee that keeps our brains working and fingers typing just for you. Witchdoctor, entertainment for grownups. Your one-off (or monthly) $5 or $10 donation will support Witchdoctor.co.nz. and help us keep producing quality content. It’s really easy to donate, just click the ‘Become a supporter’ button below.

It’s interesting to think about that period around the turn of the millennium when we were kind of getting our shit together. We were still pretty terrible, mostly as songwriters; Conrad and Luke were good musicians when they were 13. When you look back to the start we were definitely still trying to work out what it means to be a songwriter.

I think there was a turning point around when I wrote ‘This Charming Van’ and ‘Let Me Die a Woman’, and Luke wrote ‘Going Fishing,’ and he did his ‘Seaside’ EP, and Conrad started doing all these 4-track recordings while he was out on the road with [theatre show] Krishnan’s Dairy. There was a point where Conrad started to make much more interesting sounds than any of us knew about, and me and Luke started to understand how to tell a story and how to use words a bit clearer. I think some of that will come through in the orchestra show. ‘Let Me Die a Woman’ was for me a bit of an awakening of how to have that reference point where people can listen to the song and know there’s something I’m feeling or something I want them to be feeling. When you’re a teenager, unless you’re very switched on I think you write this kind of nonsense that’s either earnest rubbish or surrealist rubbish. But yeah, 20 years, it’s pretty weird.

Richard – How does having a 20-year career square with the ideas in the song ‘Give Up Your Dreams’?

Samuel – ‘Give Up Your Dreams’ was definitely tongue in cheek. It was sort of about reassessing where we were at, and what we were making the music for and reaffirming we’re really just making music for ourselves, and if people like it that’s fantastic. But we’ve always been singular in our approach and occasionally, accidentally, that has turned into some sort of commercial success. But that’s always just by chance. When you start thinking about how to recreate those kinds of things you can become focused on the wrong things. I don’t think we’ve ever made music that’s consciously tried to be radio-friendly, but you can start thinking that way and having meetings about that and stressing when those things don’t come true. But we’re not a pop band, we’re an interesting arrangement band, so the NZSO is the perfect foil for what we’ve done. Working with these incredible composers and arrangers, I think they can listen to our music and hear the difference between what we’re doing and what a more traditionally conventional band might be doing, even though we’re not avant-garde there’s still a searching quality to what we do, and it’s been really interesting hearing what someone as talented and creative as [composer] Gareth Farr can hear in our songs and pull out of them. It’s pretty exciting.

Richard – My favourite Phoenix Foundation lyric is from the song ‘Give Up Your Dreams’: “How does one transition to a mortal from a god”. It’s the rock star’s dilemma. How does one transition to a mortal from a god?

Samuel – Well, I don’t feel I’m actually famous enough to answer that question. Until you’re on Dancing With The Stars you don’t get to claim celebrity rights.

Richard – Is that a pitch? Do you want me to write that so they’ll get you next year?

Samuel – I would definitely not do it. But you know what I mean. It’s tongue in cheek. We’re not rock gods, we don’t get recognised wherever we go. There was a brief moment when we did [legendary UK TV music show Later With] Jools Holland and we were touring England and a few people would be like, ‘Hey, I saw you guys on Jools Holland,’ and it was like, wow, we’ve made it. But that was a momentary thing that probably only happened when we were wearing the same clothes and had the same haircuts as we’d appeared on the TV with the previous week.

Richard – What about in New Zealand? Are you recognised?

Samuel – I don’t even know if we’re New Zealand famous. We’ve just got our fans in New Zealand and they’re a loyal bunch, but they sort of feel more like friends these days. Maybe I’m being falsely humble, I don’t know, but that line about transitioning to a mortal from a god was definitely about, how does one get out of the mindset that you want to be a rock god and you want to be a celebrity? It sounds like someone saying, how do I relieve myself from the burden of fame? Actually, it’s kind of going, I’ve got the mindset of wanting this fame and glory but it’s a stupid thing to want. How do you rid yourself of that ego and focus on what it is that you’re good at doing, which is making music?

Richard – Is that the point where the idea of being famous and a musician stopped for you and you were able to separate those things? Or have you always been able to separate that: I want to do music, or, I want to be a rock star.

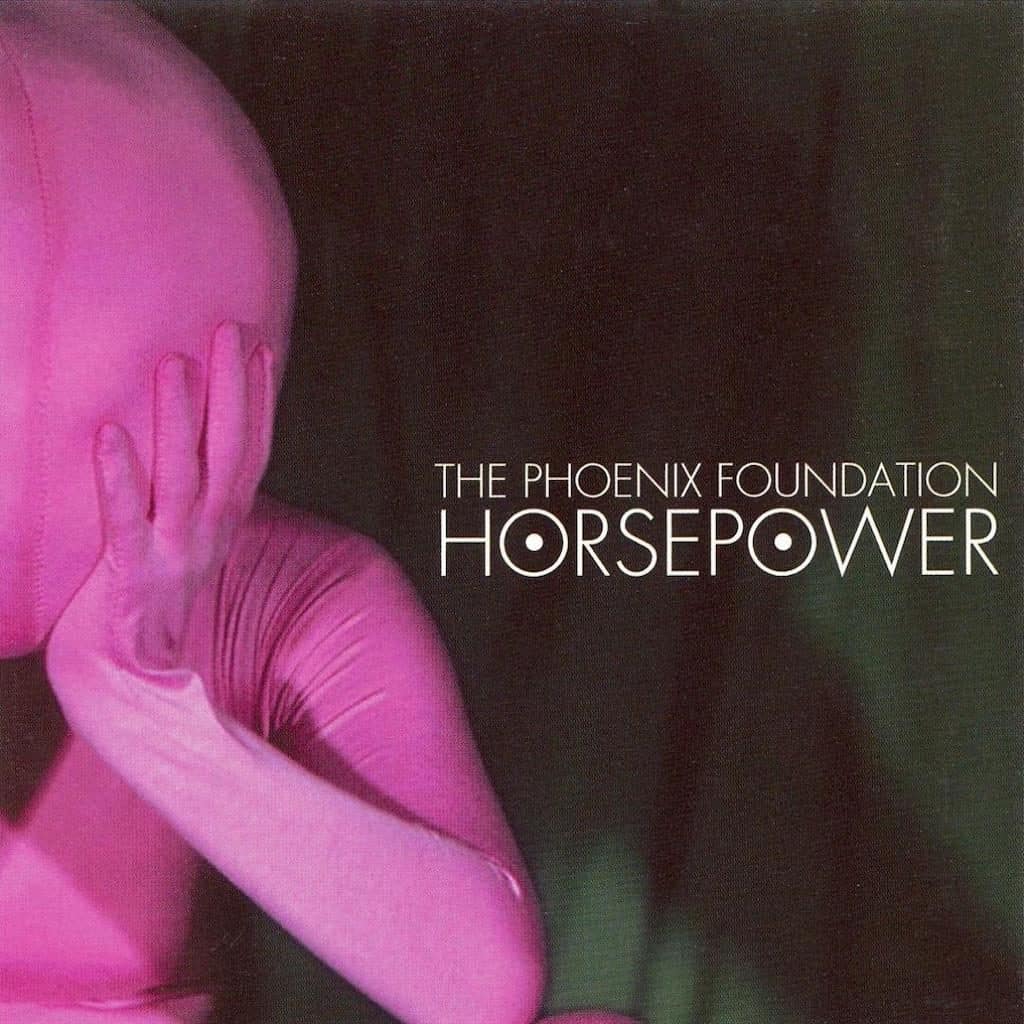

Samuel – We’ve never tried to be rock stars. I think we’d be ridiculous if we tried to be rock stars, we’re just not those kinds of people. We don’t look like rock stars and we don’t sound like rock stars. If you go back to our first album, Horsepower [2003], it’s so limp in a way, and that was a conscious choice, because that’s what we found more interesting at that time. We were listening to people like Sparklehorse and Nick Drake, gentle music, and we made a gentle album. The first thing we put out to an audience was this very chilled-out thing. Since then we’ve had rockier records and songs that have been done better. When we did Happy Ending [2007] there were a couple of songs that got played on The Rock, but that’s never happened since, and that’s not our audience. Buffalo [2010] got played on alternative radio; it didn’t get played on New Zealand commercial radio at all. We’ve never really been the darlings on New Zealand radio. The bFMs, the Radio Actives, those stations have all supported us from the very beginning when we were pretty useless right up to today, and for that we’re eternally grateful, and National Radio as well. But outside of that there’s probably Radio Hauraki and that’s about it. We’re not a radio band. So for us what’s always important is having our personality on there, not persona.

Richard – The album If Give Up Your Dreams [2015] was an attempt to reboot or change direction, where does playing with an orchestra come? Is it just another thing ticked off?

Samuel – It just came up. We got offered it. There’s no way you could ever say no to playing with an orchestra, right? It was their idea. [Conductor] Hamish McKeich we sort of know from around [Wellington], and he was very enthusiastic about it. It’s not often someone says, ‘Hey, do you want to do a tour where you have 60 people behind you making this incredible sound?’ I guess it made sense with the 20th anniversary and where we’re at but it wasn’t a conscious choice, it just happened.

And we are working on a new record at the moment and it does feel quite freed from a lot of the tensions of our last couple of records. It’s always tense making a record but it feels… I don’t know, there’s a different energy there, I’m enjoying it.

Richard – What’s the tension? Is it being stuck in a room with four or five guys for months, or pressure to come up with something, be creative?

Samuel – It’s the pressure of working in a group. There’s a push and pull to being in a band. You can push each other to do great things and you can push each other to lose confidence. That’s what any band is. When bands break up for creative differences, what they actually break up for is being sick of each other and sick of compromise. But it’s rare a really good band breaks up and they go on to do stuff that’s as good as the group, because that group energy drives people. Some people are better when they’re being driven and pushed by the people around them.

Richard – Is that the point of your work and Luke’s work outside the band?

Samuel – The soundtrack work is a job. It’s an awesome job and it’s very creative in a different way because you’ve handed the power over to a director to make the final creative choices. So that’s quite different and freeing in its own way. And solo albums, it’s the opposite. It’s like, I need to go and do something where no one tells me this is wrong. If this track order isn’t exactly right I don’t care, because it’s the one I’ve chosen. So for Luke it’s probably about spending more time on the music and being more fussy, because he loves to get everything exactly right. For me it’s the opposite. I like things to be a bit broken and not thought out. I like to make records really quickly. For Conrad it’s probably about getting away from the tyranny of songs a little bit. Everyone has their projects, and I’m a big fan of everyone in the band’s music. So it’s definitely a positive for everyone to be doing other things, but there’s something that happens when we’re all together, that’s for sure.

Richard – Has orchestral music been part of your life?

Samuel – Not really. I always enjoy going to see an orchestra but we didn’t listen to much classical music growing up. There was a point where I was about 12 when we got ‘Symphony Of Sorrowful Songs’ [Gorecki’s Symphony No.3]. That would have been the first orchestra thing I sat down and listened to over and over again. I was just overwhelmed by that dynamic. It builds so slowly and you get caught up in that thing of not realising it’s building. There’s that dynamic that an orchestra has that pop music can totally miss. They can go so quiet. It’s usually a context thing as well. With a band, if you go that quiet you just disappear into the chatter. If you’ve got an orchestra you’ve got a seated crowd that will sit there and listen.

Richard – Have you played with an orchestra on stage before?

Samuel – No. I sang backing vocals with Neil Finn when he had an orchestra but that’s my only experience of that and I wasn’t a big part of it. It wasn’t my music and I wasn’t thinking about what was happening to the music by having the orchestra there. It was like, ‘Wow, this is beautiful, we’re playing with an orchestra.’ But I think it’ll be very, very different: this is my song, and the song is evolving because of what’s happening behind me, and I can stop playing the guitar and the strings will just carry me along. There’s a few that me and Luke are just going to sing with the orchestra, and I think that’ll be incredible for us to do and people to hear. It’s the only chance you’ll ever get to hear me and Luke on stage with just an orchestra accompanying us.

Richard – Are you worried about it?

Samuel – I’m worried about if there’s things… There’s a couple of bits in a couple of arrangements where it feels like they’ve shifted the emphasis on a few melodies, and whether we now have to follow the score or whether we do what we do and they’ll fit together. Little things where we’ll make changes and they’ll have to reprint 67 scores, and everyone will start freaking out. We’re trying to work those things out now. Luke’s going through every arrangement at the moment.

Richard – Did the NZSO choose the songs you’re playing for the concert?

Samuel – It was a conversation with Hamish McKeich over a couple of months, and then he assigned the songs to arrangers. We’ve been working with the arrangers since, getting things sent back and forth, getting sent scores, which is interesting. I can read music but I don’t know what I’m looking at when I look at a score. I can’t really read music very well. The difference in skill sets between me and the guys in the band and someone in the orchestra is vast. Their discipline and knowledge is incredible. And I’d say our freedom and our ability to improvise is probably completely outside their wheelhouses. So that’s interesting when it comes together. When the band’s playing normally we can just flip the energy on a dime. Someone in the band can suddenly decide to do something differently and we can all follow that person and go down some rabbit hole, and it’s surprising for all of us. But when we’re playing with an orchestra that’s not a possibility, although there will still be that energy and tension. It must be interesting for them because what they hear from us will probably change a bit, but what we hear from them will be solid every time.

Richard – Has anything been built into the arrangements to let you jam?

Samuel – Yeah, there’s a couple of bits where the bars are not set in stone, and there’s instructions to the orchestra to free themselves up.

Richard – What about your existing band arrangements? Are you doing anything to make room for the orchestra?

Samuel – Definitely. That was our biggest concern going into it. We didn’t want to be playing a big loud rock show with an orchestra faintly heard behind it. We want the orchestra to be the focus, so some of the songs the band won’t play on at all, and some of them we’ll strip back a little, and some we won’t strip back at all. There will be ones where the orchestra’s the dominating force; some where the band will be the dominating force.

Richard – You’ve got some classy composers doing the arrangements.

Samuel – Gareth Farr is the only one I know personally, and the only one whose work I know, to be honest. I heard a lot about Claire Cowan, a lot of people brought her name up, and I think she’s got quite a bit of experience with this sort of thing. But we were given the names and went out and listened to things we’d never heard before. Every single one of them it was like, ‘Oh, they are amazing’. We just had faith in Hamish’s choices because it’s his world, not our world and I think he made really cool choices.

Richard – Some of the songs lend themselves to being orchestrated; you’ve got those atmospheric instruments. But a song like ‘Bright Grey’ is quite garage-y. I’ve been trying to imagine what [composer/arranger] Chris Gendall will come up with.

Samuel – To be honest, I have no idea how that one’s going to turn out. We have the arrangement but I still don’t know how it’s going to come together. I know that it will because we’ve got the desire to shift to make things work for an orchestra. And that’s one where I think we will have to go, ‘Right, we’re just not going to do these electric guitars’, which are the main part of the song. I’m not quite sure how it’ll work.

Richard – Chris Gendall is the interesting one for me because his classical music is quite avant-garde.

Samuel – I liked that, I thought it was exciting. We’re still working out his arrangements because his midi files were really bad. Claire’s one was really good and sounded really awesome, but Chris’s ones we were like, I think this is good, but the sound’s a bit confusing.

Richard – What are you hoping The Phoenix Foundation gets from this?

Samuel – I just want to put on a really, really incredible show. A few people have been asking if this is a transformation into a grown-up band, a legacy band or something. We’ll learn a whole lot, but the most important thing for me is that the four shows we put on are the best shows we’ve ever put on. Beyond that it doesn’t really matter. As long as those are great, that’s the whole deal.

Richard – What do you want the audience to get from it, apart from a great show? Do you ever think in those terms?

Samuel – No, I don’t really. I just want people to go away going, ‘That is not like how I’ve seen The Phoenix Foundation before’. And to feel like they’ve had an experience that’ll never be repeated. If they’re really into our music I want them to be like, I’m so glad I came to that show because I’ll never hear that again, and it was incredible. I’m not trying to teach people about classical music, or teach classical fans about rock music or anything like that.

Richard – Is Gareth Farr going to go all percussive with log drums?

Samuel – I don’t think so. His arrangements are quite beautiful. He’s got a great energy, I love talking to him about music, he’s always excited. He’s done ‘Buffalo’. That’s the Phoenix Foundation song that’s influenced by modern classical, and it’s also our poppiest, most successful song, it’s quite a weird track in that way. It’s got the Steve Reich thing on a couple of electric guitars, you get that hypnotic thing going on. With Gareth we were like, ‘Can you just push this element further and further and further?’ His arrangements have been great. They’ve all been great, to be honest. It just blows us away. Everything you get back from someone who knows how to compose for an orchestra, you go, ‘Holy shit, this is incredible, I wish we could do this with every single song we’ve ever recorded.’ People used to be able to decide to do this whenever they wanted. Recording budgets were so different. Think about someone like Nick Drake, who wasn’t successful at all but had the most amazing string arrangements. When I was 19 or 20 and heard [Drake song] ‘River Man’ and I was like, ‘Oh my God, music can be so much more’.

- The Phoenix Foundation’s new album, Friend Ship, is out now via Universal. UNEXPURGATED is a Witchdoctor series where writers dive into their interview transcripts to reveal a conversational aspect missing from typical stories.