STEVE GARDEN takes a close look at two very different films that examine male power from the female perspective in the current zeitgeist.

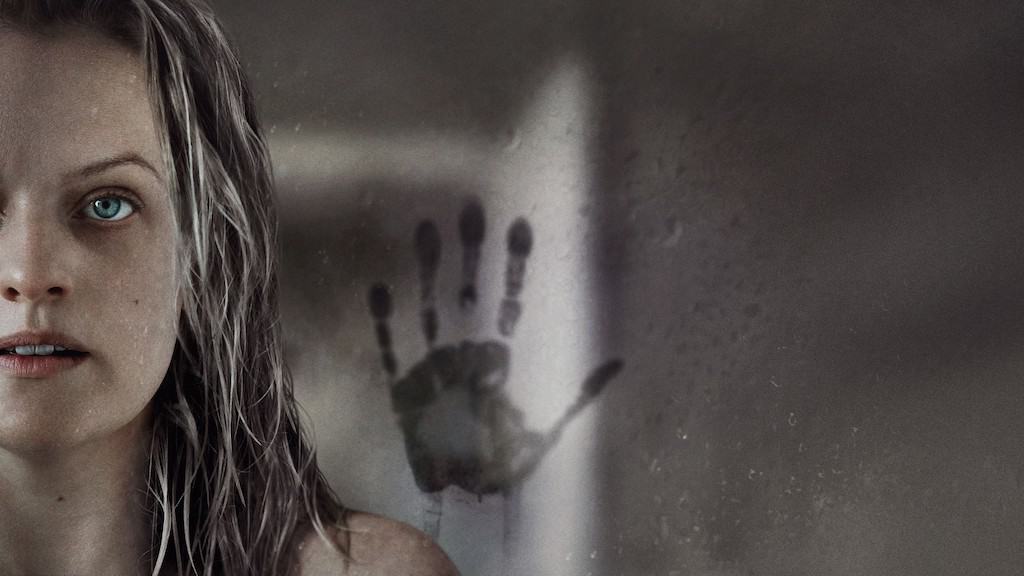

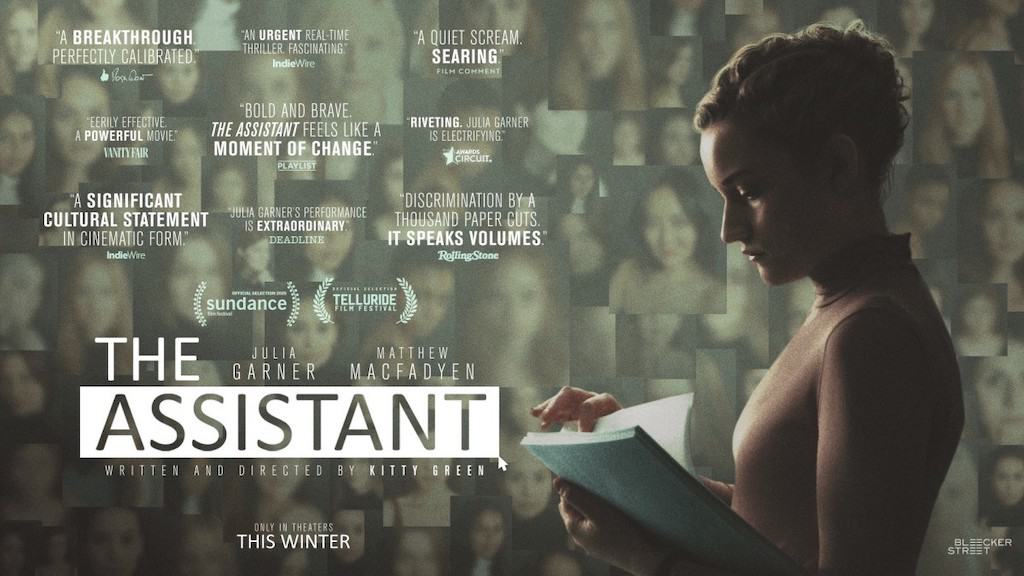

The Invisible Man (2020) is directed by Leigh Whannell and stars Elisabeth Moss who came to prominence playing Peggy Olson in the TV series, Mad Men, and will be familiar to many from her lead role in the recent TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale. The Assistant (2019) is directed by Kitty Green and stars Julia Garner, who played Ruth in the Netflix series, Ozark.

Both films ostensibly examine male power from female perspectives in the context of #MeToo, and could, in a sense, be described as psychological horror films: The Invisible Man as a mainstream thriller, The Assistant as a low-key drama.

Both are propelled by abusive male power dynamics (a toxic relationship in the former and a toxic corporate setting in the latter), each playing with the idea of invisible but palpably present male aggression. Both female protagonists are not heard, believed, or taken seriously by those around them. But otherwise, the films couldn’t be more different, particularly in terms of form, tone, and intent. Put bluntly, The Assistant is an intelligent work of art made for actively engaged viewers, while The Invisible Man is a predictable genre-piece made primarily to entertain.

Where The Assistant maintains and develops the theme of systemic abuse, keeping it central to the internal logic of the film, The Invisible Man uses it merely as a woke-conscious #MeToo pretext, a specious harnessing of the zeitgeist posing as a celebration of tenacious female resolve in defeating the unstoppable superiority of male cunning and strength.

It’s typical of the visceral schlock that Hollywood repeatedly churns out to keep itself in business, making the point – if it makes any point at all – that for women to succeed they have to outplay men at men’s games using men’s rules.

Melbourne-born director Kitty Green succinctly describes her film as quiet but with a loud subject, and I can’t recall another (including Bombshell, The Morning Show and Big Little Lies) that so deftly reveals the difference between everyday society as women experience it to the way it is for most men, a daily reality that many men may largely be unaware of due to the male-centric shape of the world.

This viewpoint is the overriding focus of the film, quietly showing how male privilege and abuse is matter-of-factly normalised by fear, ambition, conscious/unconscious acquiescent ignorance, or possibly worst of all, indifference.

Eschewing emphasis in favour of minimalist restraint (reminiscent of European cinema), Green focuses on the mundane routine of her young office assistant protagonist, relegating unsavoury details (which would be milked for all they are worth in a mainstream film) to off-screen space. This includes “the invisible man”, the never seen (only heard, mostly at a distance) Weinstein-like mogul that everyone essentially enables. It’s a superb conceit that adds power and weight to her argument, whereas in The Invisible Man the unseen threat is used to effectively glorify violence.

Of course, the implications of The Assistant reach beyond the Miramax-like office environment of the film’s setting to encompass, well, any injustice or discrimination you choose. Because in essence, it encapsulates a profound, yet equally matter-of-fact truth about society and complicity.

That Green conveys these subtleties with formal mastery and style is, particularly for someone with my enthusiasm for cinematic formalism, an absolute pleasure. The fact that this is her first foray into fiction filmmaking – having previously made three excellent films that blur the line between fiction and non-fiction, particularly Casting JonBenet (2017) – makes it all the more remarkable, and signals a substantial new voice in world cinema.

* The Invisible Man is currently screening in selected NZ cinemas. The Assistant is available for pay-for-view screening from the usual places.