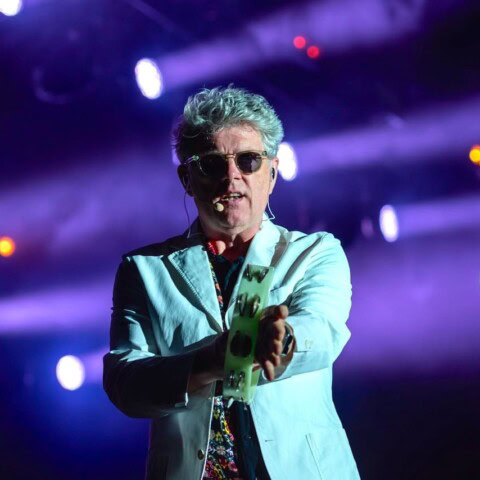

RICHARD BETTS chats with Michael Norris – a finalist in the SOUNZ Contemporary Award, whose work uses electronics along with the sound of a whale vertebra.

SOUNZ, the Centre for New Zealand Music, has announced the three finalists for its annual SOUNZ Contemporary Award, the top honour for local classical composers.

It’s a fascinating selection, featuring two of our leading young composers, Celeste Oram and Alex Taylor, who are both conducting doctoral work in the USA. Oram’s piece, a loose affiliation of alleluias, is a beautiful concerto for improvising violin and three voices, while Taylor has collaborated with visual artist Simon Ingram to produce Assemblage, an atmospheric work for orchestra and computerised painting machine. They face off against three-time winner Michael Norris, whose Matauranga was written to commemorate 250 years of James Cook’s arrival in Aotearoa.

I caught up with Norris in June 2019 for the NZ Herald, ahead of the NZSO’s world premiere performance of Matauranga. The full interview is presented here for the first time.

Richard Betts – I’m not sure how to explain what it is you do. To my ears there’s quite a range to your music. How would you describe your style?

Michael Norris – Yes, it has gone through a lot of different interests over the years. I’m interested in writing for instruments, that’s the first thing. I did my Master’s in electronic music and realised at the end of sitting in a studio for a year that I needed some human company. That was 1997. Since then I’ve largely written for instruments. But more recently I’ve developed live electronic practice. That’s primarily working with instrumental sounds and processing them in real time. The piece I’ve written for NZSO [Matauranga] will feature those electronics. Everything will be created in real time, so there are no pre-recorded elements at all.

Richard – Are the electronics run by someone or is it programmed to respond on its own?

Michael – They are run by me. I have written a number of electronics systems that do respond [independently] but they’re not terribly reliable, and I think when you’re writing for the NZSO you want something that’s reliable. So I’m operating when the electronics do their processing and I’ve programmed that all in but you will still clearly hear the effects of it live.

Richard – The music of yours that I know best is chamber or instrumental music. Is there a connective thread between those and the orchestral works you write?

Michael – Chamber music is always a good testing ground for ideas but, at the same time, writing for a chamber ensemble and writing for orchestra are very different things. With orchestra the acoustics really change the equation, and I’ve heard over the years some contemporary orchestral works that I didn’t think worked because they were treated like a large chamber ensemble, to the point where it was hard to make out what was going on because the acoustics just blur everything. So writing for orchestra you really have to understand not only all the instruments you’re writing for and their limitations, but also the characteristics of the space you’re in. I guess my chamber works probably deal a lot more with smaller scale timbral developments, using a lot of extended techniques and things like that. Because when you’re in a smaller space with fewer musicians it’s much easier to hear the effects, and some of those effects don’t scale up to the orchestra at all. This piece is probably the most radical of my orchestral pieces in terms of how I’ve treated the orchestra, but by the standards of my other works, it’s moderately conventional.

Richard – Have you written for taonga puoro [traditional Maori instruments] before?

Michael – No, this is my first time. I have done some work with [respected taonga puoro practitioner] Richard Nunns before using live electronics, but that was not in any official capacity, it was just a sort of jam session one night. I’ve been on a couple of wananga festivals with Richard and more recently with [taonga puoro musician] Horomona Horo. That was useful for korero, how you bring these worlds together. I’ll confess it’s not without its problems. What’s really excited me is bringing the live electronics into the equation as well. The live electronics are all coming from the sounds of the taonga puoro, they’re not coming from the orchestra at all, it’s like a large echo chamber of those beautiful sounds of the traditional instruments that resonate throughout the piece. The electronics sustain them and shape them and highlight them and amplify them, because they’re quite delicate and fragile sounds. This amplifies and strengthens their voice.

Richard – Taonga puoro are more than just musical instruments, they carry the culture of a people. How do you factor that in?

Michael – Yeah, they all have stories about them, particularly the putorino, which was associated with the spirit world. I sort of evoke that subtly but I haven’t gone too deeply into that world or the symbolism of each instrument. The concept of the piece is around evoking James Cook’s arrival and the flora and fauna that he and Joseph Banks and the other botanists who were there met along the way. That’s one aspect of the piece. And the taonga puoro represent that because they’re made out of the natural flora and fauna of New Zealand. There’s an instrument made of albatross bone, there’s various native woods in there, horotiti, which is made from the vertebra of a whale. So a lot of these pieces that were made by [musician and instrument maker] Alistair [Fraser] himself, a lot of the resources were found on the beaches and in the woods of New Zealand. So that’s one aspect of the story. But the other aspect that’s in there, it’s woven all the way through. The title is Matauranga [knowledge, understanding, wisdom, skill] and that reflects Cook’s journey of discovery, but also reflects the Matauranga Maori, the forms of cultural and artistic knowledge Cook would have encountered. There’s lots of discussion in the journals and the various writings associated with the voyages of the flax weaving, the tattoos, the carving on the houses and waka, so lots of fascination with Maori art, I guess, is reflected in the journals, particularly the first voyage. And there are two ideas subtly underlying the piece. The first is harakeke [flax] weaving, particularly tukutuku panels, and the idea of weaving which comes through sonically in the live electronics. If, say, Alastair is playing five notes, the electronics will pick up those five notes and fade them in and fade them out for a while, and each of the other notes will do the same at other times, so you get this wave-like weaving effect of those five notes after he’s played them. These electronic textures represent that weaving. Also the putama as well, which is a particular type of tukutuku panel, the idea of building layers. So it starts with one note which gets woven then a second note gets built on top of that then a third note; that was an image I had in mind as well. The final image is one simply of the sea, reflecting Cook’s voyage. At the beginning the porotiti, [humming disc] plays into the microphone and is put through a process called crenulation which turns the sound of the porotiti – this is the whale vertebra – into a sound almost like the sea. You can hear the waves breaking. That’s not a pre-record of the waves breaking, that’s the sound of the porotiti being granulated in real time through a computer.

Richard – So the way you use electronics is in a wholly predictable, controllable way, it’s not random.

Michael – That’s right. The only variance built into it is when each of these processes start. I can react to the tempo, to the conductor, to the player. It doesn’t have a pre-programmed tempo, but the sequence of processes is pre-programmed, so I know I need to press this button at this time. Of course, Alistair will have variance from performance to performance as well. Those instruments are hard to control; it takes a lot of skill to get a sound out of some of them, let alone actually play a tune I’ve written, so there will be variances from performance to performance and the electronics will therefore change a little bit, but nevertheless there is an overall sequence it follows.

Richard – This work is composed for the 250 commemoration of Cook’s arrival in Aotearoa. That event is a celebration for some people but not for others. Is that something you’ve tried to navigate or have you kept away from that point of contestation?

Michael – It’s a good question and has come up in every interview, and should do, rightly. I’d be lying if I said this was an easy piece to write. It’s caused me a lot of thought. I’ve been to my local marae at the university and talked to them about it. We’ve had some interesting discussions about decolonisation versus re-Maorification, which I think have come into it. I would say this piece slightly steers away from it in that it doesn’t necessarily directly confront the legacy of colonialism, it’s more than an evocation than a celebration. I think in the end my feeling about this is that the piece is not celebratory but it is atmospheric. It must have been a strange and unusual time both for Cook and for the local Maori as well, to have this cultural collision for the first time, as well as the environment which would have been very different from the landscape of Aotearoa today. The music in the last third, the taonga puoro player picks up the big traditional trumpet and sounds out quite aggressive calls which are picked up by the trumpet and bounced back to the orchestra in quite dissonant, thick scoring. So that’s a nod at the conflict I still feel in this piece.

Richard – Are you a composer who writes to commission or do you compose whether you know a work’s going to be played or not?

Michael – I don’t think I’ve ever written a piece without having a performance in mind. That’s not to say that every piece has ended up being performed, but I would always want to write with a particular performer in mind. When I’m writing for the NZSO, I have a certain understanding of their players and what they’re capable of. As opposed to if I was writing for an amateur orchestra, which has a different set of capabilities or skills.

Richard – I interviewed [young composer, and previously Norris’s student at the New Zealand School of Music] Salina Fisher last year, and she cited you as an important influence. What do you learn from your students?

Michael – I think of it slightly more holistically. Of course I learn stuff from them but I learn a lot just from the experience of teaching. How do you teach composition really? You can teach people the aspects of an instrument, you can teach them which notes to write, but it doesn’t necessarily make them a good composer. Trying to put into words my experience of composing music, and putting them into simple words that would be understood, is a very challenging task, and not one I always feel like I necessarily succeed in. Often it’s more about leading students through an experience we share together. For example, about 10 years ago I was in Vienna and heard an amazing piece I’d never heard before on solo violin and was blown away and then spent the next couple of months trying to track down this piece. I bought the score and the recording, and that became an important piece for me. I decided to teach a course based around this piece – not the entire course but the first quarter of it. That was one of the ones Salina took and her being a violinist she took to it like a duck to water and made some wonderful music that was modelled on this piece without copying it. That experience of having to teach why I love a piece of music and what it was about this work that excited me, and then seeing that piece infect the other students with its enthusiasm, that was rewarding.

Richard – What was the piece?

Michael – It’s not a well-known piece, it’s by an Italian composer called [Salvatore] Sciarrino, Sei Capriche – Six Caprices. It’s kind of modelled on the Paganini Caprices but with contemporary techniques.

Richard – You’ve created your own computer programs, and been involved in the development of SoundMagic Spectral and Spin Drift. Are you interested in electronics generally, or just what they can do to sound?

Michael – I’ve done a few other programming projects but most of them are in sound. I do lots of little things on my computer to automate university bureaucracy. So yes, I am interested in programming for programming’s sake but there has to be a payoff for me, I’m not just doing it for fun, it’s got to have some impact on my life. Sonically, it’s usually because I’ve dreamt up some sort of vision of what I’d like to achieve and then realised there’s not really anything off the shelf that’ll do it, so I have to create something myself. In Matauranga there are a few features I needed from the electronics that I haven’t used in previous pieces.

Richard – You’re involved in a lot of things. As well as composing and programming, you’re head of the New Zealand School of Music in Wellington and co-director of [contemporary chamber orchestra] Stroma. Is that a personal preference or is that the nature of working in classical music in New Zealand?

Michael – Some composers are very single-minded and they just do their thing and don’t have a lot of other strings to their bow. Maybe it’s my personality and I get bored really easily and need to interest myself in a variety of projects, I’m not sure. But I guess I find there’s something about programming the software and writing for the orchestra that are similar in terms of intellectual challenge. I know I can do both of them but I don’t always know how I’m going to do it at the start. Trying to break those problems down into smaller components and work through them slowly is a similar kind of task. And when I’m halfway through them I sometimes wonder why I did it. When I get to the end I do think it was worth it.

Richard – Your bio says you’re interested in post-tonal music. Michael Norris, why do you hate tunes?

Michael – [laughs] Post-tonal music doesn’t have to be non-melodious at all. In fact, most post-tonal music probably is melodious or melodic. Post-tonality is only about the dissolution of the common tonal systems, chords I, IV and V. Post-tonality incorporates pretty much all of the film scores we hear today. Most of those don’t operate in the way Beethoven or Mozart wrote music. I taught a course last year on the relation between late-Romantic music – Wagner and Richard Strauss – and Hollywood film music. I loved teaching that course and I loved transcribing all the great film extracts I knew from my childhood. I spent one lecture looking at sci-fi. Lots of Star Trek and Star Wars and so on. So I don’t hate melodies at all. In Matauranga you’ll hear the taonga puoro play a lot of melodies, it’s all melodic, but I guess I’m interested in harmony that is not your traditional way of harmonising a melody. In this piece the harmony comes from the melody and not from some other tonal system I’ve invented.

Richard – You recently wrote a concerto for violinist Amalia Hall [some months after this interview, the concerto, Sama, won Norris his third SOUNZ Contemporary Award].

Michael – Yes, it was commissioned by Orchestra Wellington for her to be the soloist.

Richard – How do you write for a virtuoso violinist?

Michael – I could talk to you all day about that. Here’s another example: you know I was talking before about how writing for chamber ensemble and orchestra are two different things? Well, even writing for orchestra, writing for a violinist in the violin section versus writing for solo violin are two very different things. So the concerto was written in a way that a) highlighted her virtuosity but b) made much more idiomatic use of the instrument. There are things you can do when you’re a soloist that if you got a whole section to do really wouldn’t work very well. So again, that’s where thinking about the acoustics and the physical reality of the situation really comes into play and what you write. The violin is not my instrument, I’m a clarinettist, and it’s taken me a good while to feel comfortable writing for the violin. Writing a concerto you have to feel pretty comfortable, and 99 per cent of what I wrote was fine, I only had to tweak a couple of things for her. But it’s taken me a long time. I’m 40-something and it’s taken me until now to really understand the violin. The strings are technically challenging to write for. When I teach strings to my students we spend a long time on them because there are so many things you can do with them, they’re so versatile. They have massive timbral variations from arco to pizzicato to bouncing bow to legato bow to playing with the wood of the bow to double stops to harmonics. And people are still inventing new sounds.

Richard – Do you remember which qualities of Hall’s playing you wrote to?

Michael – Her fearlessness. I remember bringing what I thought were quite difficult chromatic runs that feature in the concerto to her dressing room for the first time some months prior to the premiere, and she sight-read these runs almost without blinking. Phrases way up the top of the fingerboard that most violinists would turn a pale shade of green at, she revelled in. There were one or two bits I wrote that were… let’s say ridiculous in terms of what they expected a human to be able to perform, and she really tried hard. There was only one bar in the end I had to revise because it was beyond the limits of human physicality, but there were a couple of other bars that were right at the edge and she performed them at the concert and they sounded amazing. One of my favourite bars of the concerto is a passage that’s supposed to sound completely on the border of falling apart and she nailed it.

Richard – Do you ever know before you hear it in concert whether a new work is successful?

Michael – Somewhat. You have an inkling. Having said that, your view of a piece does change after you’ve heard it, particularly after you’ve heard it a number of times. You tend to form a slightly different view of it than before you heard it. I don’t know what my view on [Matauranga] will be after I’ve heard it.

Richard – Do you do a lot of revising once you’ve heard a piece?

Michael – Yeah. Not major revisions but often I make a few minor revisions, particularly if I know a piece is going to get a second performance at a later date. I might take that opportunity to fix something that was bugging me in the piece.

Richard – I was talking to a composer the other day and he said the second performance is the most important because you never know if you’re going to get it.

Michael – That’s true. Sometimes you have to make that performance happen, you can’t rely on other people making it happen. One aspect of being a composer I’m not great at is lobbying people to get my music performed again. I’m usually too busy thinking about the next project to invest a lot of time and energy into getting a piece re-heard.