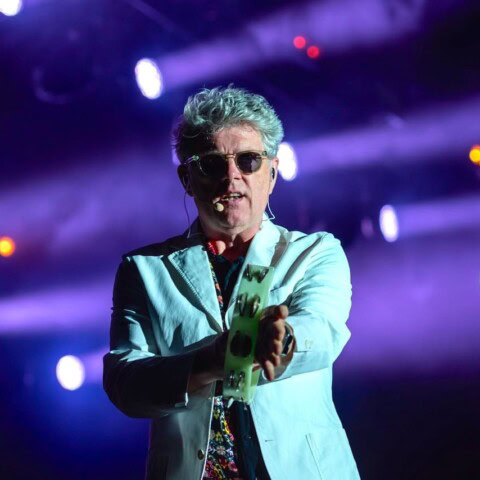

In Witchdoctor’s famous BLINDFOLD TEST, we invite a musician into an audiophile sound lounge and play them a provocative record selection. This week, former Thompson Twins and sometime International Observer TOM BAILEY is put to the test at Auckland’s Audio Reference showroom. GARY STEEL is the DJ selector.

Tom Bailey has a fascinating backstory. Raised in Sheffield, England, he was a piano prodigy whose love of Bach has been a lifelong affair. He was to go on to huge stardom in the 1980s with his group the Thompson Twins with songs like ‘Hold Me Now’, ‘Doctor Doctor’, ‘Lay Your Hands On Me’ and ‘King For A Day’, and later, the duo Babble, while also establishing himself as one of the most respected session keyboardists and producers. In the ‘90s Tom retreated to a quieter life in Auckland, New Zealand where he worked on his electronic dub act International Observer and curated an international Indo-fusion group, the Holiwater Project, amongst other outlier musical activities. Recent years have seen Tom return to London and relaunch himself as a solo pop artist. He has toured extensively, performing a mixture of the Thompson Twins hits and new material from his first solo album, last year’s Science Fiction.

JOE COCKER – THE MOON’S A HARSH MISTRESS (Album: I Can Stand A Little Rain)

Tom – I want it to be Joe Cocker. I like his voice. He was a big softie and from my home town. The Sheffield Steel album was recorded at Compass Point, so I heard some of the stories about Joe there, which were all very warm-hearted. He completely seduced everyone, they loved him. His reputation was of a very kind-hearted chap.

Gary – Growing up in Sheffield did you feel a connection to artists in general that came from the area?

Tom – Not particularly! I do remember as a teenager going out to the Saturday night hop where they were playing Motown dance records and someone putting on ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ by Joe Cocker, and everyone stopped dancing so the DJ, after awhile, took it off, and replaced it with something to dance to, and I remember feeling a big disappointment to that, that our musical tastes were kind of being narrowed down to what you could tap your foot to. And ‘With A Little Help From My Friends’ was a staggering piece of work, the live and recorded versions. I got to meet the guy who produced it, Denny Cordell. I got to ask him his production techniques, and he said, “I don’t know anything about music, I just try and get a good party going in the studio. Just give everyone a good time and hope that the best work comes out.” He did classics like ‘A Whiter Shade Of Pale’ (Procol Harem), and some other all-time killers of pop/rock radio history.

Gary – Was soul a big thing in Sheffield during your school days?

Tom – Well, at school there was a playground division between mods and rockers. And under the influence of my older sister I became a mod rather than a rocker, in terms of who I’d rather get beaten up by (laughs). And then a little bit later when I was in secondary school, locally there became a division between soul and prog, and I very definitely drifted toward the prog camp. Although it was cool with the prog to say ‘I like soul as well’, whereas if you were a soul fanatic you had to diss prog at any opportunity and threaten to beat you up for having a Nice album.

CABARET VOLTAIRE – PARTIALLY SUBMERGED (Album: Voice Of America)

Tom – Oh, Cabaret Voltaire, another Sheffield band.

Gary – Did you know those guys at all?

Tom – No. Around my last year in Sheffield they were very much present on the scene. And a rumour went around that they had to buy some equipment to avoid paying tax. I was so jealous. I’ve heard this but not for 30-odd years or something. The sound of the electronic drums reminds me of a Vini Reilly (the Durutti Column) track as well. Sort of like soft noise.

Gary – It’s interesting that this 1980 album is very analogue-sounding and lo-tech whereas by the mid-‘80s they’d gone extremely what seemed at the time to be very hi-tech and slick. Those Dalek voices!

Tom – I was thinking it’s almost Human League. [sings] “Listen to the voice of Buddha!”

Gary – There’s something I could never understand and maybe you could put some perspective on it, which is that at this point, around 1980, there were all these avant-garde electronic groups like Human League and Cabaret Voltaire, Ultravox with John Fox, and within two years they were synth-pop New Romantic bands. How did that happen exactly?

Tom – I know exactly what happened because I was very impressed and influenced by this idea. It was suddenly okay to be pop again. For so long we’d had this kind of snobbish refusal to do anything that was too successful – always be outsiders, always be underground, always be difficult to consume – and it was Phil Oakey from the Human League who said actually, “You know, Top Of The Pops is going to exist regardless and it’s going to be full of this guitar thrashing post-punk stuff which has run its course, and we’re actually what’s happening but we’re all too cool to just write a pop song.” And he was right. For me it’s one of the founding principles of that synth-pop movement, is realising – because we were all experimentalist nerds – that it was okay to be popular. But maybe it’s a difficult thing for most people to appreciate that it was profoundly serious, but for us it was.

Gary – What made everybody decide to do that all at the same time? The classic ones were the Gang Of Four and even The Cure going from all those very depressing songs to outright dance-pop.

Tom – Now that you mention those I think it’s because, for some other reason perhaps, the nightclub became the marketplace for ideas, and nightclubs had sound systems and played dance records with low lighting conditions and people got crazy in them, so it became for me very interesting and that’s why you went to lurk in here and expose yourself to new ideas.

Gary – And what you were saying about songwriting, these guys obviously tried. I remember ‘Sensoria’, a song from around ’84 or thereabouts where they got quite slick and the camera on the video went up in the air and came down again which seemed amazing at the time. It was their attempt to write a pop song, but they clearly didn’t have what it took…

Gary – And what you were saying about songwriting, these guys obviously tried. I remember ‘Sensoria’, a song from around ’84 or thereabouts where they got quite slick and the camera on the video went up in the air and came down again which seemed amazing at the time. It was their attempt to write a pop song, but they clearly didn’t have what it took…

Tom – Oh right, when someone invented that swinging camera. Maybe they just weren’t interested, really. Other people in that Sheffield environment were definitely interested, and if you compare Sheffield and Manchester at the time we had a lot fewer groups but a lot more success. So it was fairly intense, and our batting average was way up there. And not all experimental electronics either, because there were people like Def Leppard. Heavy metal was alive and kicking in the North of England although its real centre of gravity is Birmingham for some reason, maybe because of the Ozzy Osbourne connection. I remember seeing an old drummer friend with a very broad Northern accent. He said ‘I’m in a new band’ and I said ‘what kind of music are you playing?’ and he just said ‘eavy!’ [laughs]

BLACK UHURU – SHINE EYE GAL (Album: Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner)

Tom – I don’t know it, but I’m enjoying it. It sounds like Sly and Robbie. I got that on the first drum roll. But the vocalist I can’t place.

Gary – It’s Black Uhuru with Michael Rose, from 1980.

Tom – Musically what I like about this is that there’s some force about it but there’s a feeling of sadness, a melancholy. They were touted as the next Bob Marley, who had broken it open and there was then a fight on to see who would become the first superstar band, and Black Uhuru or Third World was going to be it. But it’s a weird thing, with a few exceptions it’s never mutated into pure pop, it’s always stayed in the territory.

Gary – Were you always a big dub and reggae fan?

Tom – No, when it first happened I found it very difficult, I must say. A bunch of my friends at college moved to Leicester where they encountered the reggae revolution on the streets there, and I went to visit them, and they wanted to get stoned with us and listen to reggae records and I was ‘come on, haven’t you got any Genesis?’ I didn’t get it for awhile and it was when I moved to South London and started hearing it as the music in the streets, and found a rebellious spirit and political dimension to it. There was a reason for it. I think I flirted with that unashamedly and ended up going to work with people with Dennis Bovell and Linton Kwesi Johnson, who had been the very guys I’d wanted to take off the record player in Leicestor.

Gary – Worked with, what do you mean by that?

Tom – Well, the first Thompson Twins record was partly produced by Dennis Bovell as a result of my connection with The Slits, and he did their brilliant first album (Cut), I was so impressed with that. But it wasn’t a pop record. I thought they were going to clean up, and that was a sign that I just needed to think things out a bit more clearly.

NEW AGE STEPPERS – PRIVATE ARMY DUB (Album: Massive Hits Vol. 1)

Tom – I’ll mention the fact that it’s very badly played, for a start. No idea, could be a rehearsal of any one of a thousand groups.

Gary – It’s a 1980 collaboration produced by Adrian Sherwood with Ari Up of The Slits, Mark Stewart and Mark Stewart and Bruce Smith from The Pop Group. So Dennis Bovell produced the first Thompson Twins album (A Product Of… Participation, 1981)?

Tom – The first half of it, and then we jumped ship and finished the rest of it ourselves. But he probably produced four or five of the tracks on that first Thompson Twins record, which is not a commercial record at all. I think we were still trying to be a UK Talking Heads or something, but in the same way that the Talking Heads had expanded into an Afro-groove big band, I had at the time ambitions to do a similar thing.

The vocalist is Ari Up? Did you read Viv Albertine’s book? It’s so entertaining, insightful, and early in the story she admitted to all sorts of non-punk affiliations. Her first live gig was the Edgar Broughton band. Vivian Goldman, she was a stalwart on the scene, as was Mark Stewart from the Pop Group. Bruce Smith was the drummer in The Pop Group and the Slits. And there’s Steve Beresford from the Flying Lizards. The connection I had with them was someone called Dick O’Dell. Or ‘Disco Dell’ we used to call him, who managed The Slits and various other people. He’s still around. I almost made a record with him.

Gary – What do you make of that Adrian Sherwood thing?

Tom – In general? I like it.

Gary – That English take on dub, turning it into an almost industrial-sounding thing.

Tom – I think it had lots of legs. One of my big favourites was African Headcharge.

GRACE JONES – PULL UP TO THE BUMPER (Album: Nightclubbing)

Tom – ‘Pull Up To The Bumper’. Here’s my confession: it took me years to realise that this song wasn’t about cars. [laughs] I’m always the last one on the block…

Gary – So obviously this is Alex [Sadkin]…

Tom – Alex, Sly & Robbie, Steve Stanley, the whole gang, and Chris Blackwell looking over everyone’s shoulder. Being the right kind of record boss, steering from a distance and saying ‘come on guys’.

Gary – I find it fascinating because clearly there was something going on that made it work so well.

Tom – It’s Wally Badarou as well on keyboards. It’s the Compass Point Allstars that make it such a fantastic sounding record, and Steve Stanley engineering and mixing. But they knew they were onto something, and Grace is almost the perfect example of a self-evident superstar. She walks in the room and everyone goes ‘wow!’ and she opens her mouth and everyone goes ‘wow!’ and then you hear her ideas and everyone goes ‘wow!’ She had made previous disco records which weren’t that inspired. But it became good when she joined with the Compass Point Allstars and there was a sort of island feel about it. She was no longer pretending that she hadn’t come from Jamaica.

Gary –Was (Thompson Twins producer) Alex Sadkin important to you?

Tom – Oh yeah. And I’ve got to say that I learned more from him than from anyone, really. Alex was a nice guy, he was very smart, but he was lucky also to come from a peculiarly technical background. He actually graduated in marine biology, so he was a beach guy, which was also handy when you were working at Compass Point because he could point out the dangerous sharks and the not so dangerous sharks.

Gary – Not the ones in the music industry though.

Tom – A few of those as well! And some of my fondest memories of Alex were going snorkelling with him. Actually, there’s a piece of Thompson Twins music called ‘Leopard Ray’ after that. But he started when he dropped out of his career path. He was in a band, oddly enough, with Jaco Pastorius, they were in high school together, and by the time he came out of university Jaco had gone on to become a megastar. He decided he wanted to be in the music business as he could play the saxophone very badly. Someone told him about a studio in Miami – because he lived in Fort Lauderdale, Florida – that was owned by the BeeGees at that point, called Criterion. And in those days, which was the peak of the success of the ‘70s music scene, studios were a one stop shop for everything, and they included a cutting suite where you cut vinyl, so he became the assistant to the master cutting engineer at Criterion, Miami, and that’s where he learned, and he told me about this, that you can only fit so much on a record. You can’t have the biggest, fattest bass sound, the wildest, wackiest, most echo on a snare in the world, the loudest vocal, it’s impossible, and it’s a compromise. It’s the cutting engineer who has to deal with that. So, having learned the hard way how to cut a great record, he had a short but brilliant career there before he started being a record producer himself.

And just to fast forward to another incident… I was at a cutting room with one of the great all-time cutting engineers called Arun Chakraverty in the mastering room in London, and I said to him, ‘Have you ever received a master tape that you didn’t have to change in any way in order to master it onto record?’ and he said, ‘Only once, and it was Alex Sadkin’s mix of ‘Hotel California’ by the Eagles.’ He said it was sonically perfect so he could just plug it in and the tape went to vinyl. Everything else you’re compressing, you’re EQ-ing, you’re riding levels and all this kind of stuff in order to get the best compromise. So Alex knew his stuff, it sounds great because it will fit in, which also means you can have a nice loud synthesiser there or bass there or a vocal there, and most people don’t understand that because they never look at it from an engineer’s point of view.

And just to fast forward to another incident… I was at a cutting room with one of the great all-time cutting engineers called Arun Chakraverty in the mastering room in London, and I said to him, ‘Have you ever received a master tape that you didn’t have to change in any way in order to master it onto record?’ and he said, ‘Only once, and it was Alex Sadkin’s mix of ‘Hotel California’ by the Eagles.’ He said it was sonically perfect so he could just plug it in and the tape went to vinyl. Everything else you’re compressing, you’re EQ-ing, you’re riding levels and all this kind of stuff in order to get the best compromise. So Alex knew his stuff, it sounds great because it will fit in, which also means you can have a nice loud synthesiser there or bass there or a vocal there, and most people don’t understand that because they never look at it from an engineer’s point of view.

Gary – Speaking of sound quality and mastering, have the Thompson Twins records been remastered?

Tom – There’s a label called Vinyl 180 in England, and they re-release albums on 180 gram vinyl. They’ve done the earliest Alex Sadkin-produced record, and then the Steve Lillywhite ones, so we had to write new liner notes for it. They do a limited edition on yellow vinyl to begin with and then it comes out in black vinyl. Somebody’s talking about a box set as well to finally nail the proper Twins… and he actually, I don’t know if he’s going too deep into it but he’s obviously a fan that knows the b-sides and stuff.

10CC – ONE NIGHT IN PARIS (Album: Original Soundtrack)

Tom – This sounds familiar but I don’t know what it is. I’m thinking 10cc. Is it ‘One Night In Paris’?

Gary – I know that you had Godley & Crème doing your videos.

Tom – And the track that’s coming up, ‘I’m Not In Love’, is the biggest radio hit of all time in the UK. I’m impressed by its experimentalism, and it’s music with a sense of humour, too, which can sometimes work and sometimes not. We recorded in their studio in the South of England called Strawberry Sound, in a little ‘80s man-cave. We had to move all the pictures of naked women, because softcore porn was the interior decoration of the studio! They never expected any women for which that was going to be a problem to enter this space. They had one in Manchester, Strawberry Studios, and then Strawberry Sounds, which was in Dorking in Surrey. And we recorded an early single there, so we spent a few days there. This sounds almost Emerson Lake & Palmer.

It’s all so interesting, because I have some sympathy for the argument that wherever you look in rock and roll there’s always a Jewish connection and they’re a profoundly Jewish band. And so, just looking at them from that perspective it joins the Carole King/Paul Simon continuum.

It’s all so interesting, because I have some sympathy for the argument that wherever you look in rock and roll there’s always a Jewish connection and they’re a profoundly Jewish band. And so, just looking at them from that perspective it joins the Carole King/Paul Simon continuum.

Interestingly, the remake of ‘I’m Not In Love’ was by 3cc, because you know what 10cc means… It was an average ejaculate. And because they were older they’d gone down to 3cc. [laughs]. Which I thought was typical of their humour. They invented something called The Gizmo. Do you remember that? A rotary plectrum that they thought was going to change the world, but it wasn’t taken up in any significant way by anyone else. I always wanted to try one of those.

Gary – You never got to try one?

Tom – No. Because it was taken over by a kind of electromagnetic plectrum that made the string vibrate invisibly. They were such stoners.

THE NICE – KARELIA SUITE (Album: Five Bridges, 1969)

Tom – This is Keith Emerson doing Sibelius. Must be The Nice.

Gary – Obviously it’s a somewhat clumsy interpretation. From this distance what do you make of such a thing? Is it still enjoyable to you?

Tom – Well, you know… I’m going to sidestep that question by saying that as a keyboard player for so long we were expected to keep our catalogue of understanding to one side and just play the chords behind the guitar player who was showing off… The good thing about Keith Emerson was that he competed with the guitarists, so you got the same level of satisfaction in terms of the showmanship and bravado and kind of cock rockiness as you would for Jimi Hendrix. No one had made keyboard playing quite so extravagantly out there, and he turned the keyboard into a rock and roll icon instrument. What was there before? Lots of great keyboard playing but it wasn’t symbolically the same as this. Booker T and the MGs, fantastic but you know… You wouldn’t pose in front of the mirror with a Hammond organ until he showed you how to do it, because every kid on the block was posing with a guitar. In that superficial but profoundly important sense he opened it wide open. The Nice came to my home town, but I didn’t go to the show. Monday morning at school they were going “Wow! You missed a great gig on Saturday night!” Their second release was ‘Brandenburger’, based on Bach’s Third Brandenburg in G, which I already knew of course from its classical context, so that was it, it linked arms from behind the bike sheds for me at that point.

It’s not cheesy to me, I mean there are precedents with people like for example Jacques Loussier playing Bach in a kind of cool jazz swinging style, which were massively popular. But for some reason those things weren’t sexy to me. I can listen to them now, they’re beautiful, but not sexy in the way that rock and roll requires things to be sexy.

Gary – What do you think of classical and rock together? Of course a lot of prog bands have a European art music tradition behind them but… do you think it was ever successful?

Gary – What do you think of classical and rock together? Of course a lot of prog bands have a European art music tradition behind them but… do you think it was ever successful?

Tom – Oh yeah, totally! There are obviously moments when it becomes idiotic but you’ve got to be open to any kind of fusion, that’s where things get interesting. Ultimately, otherwise we’d just have Elvis Presley over and over again. And it’s a kind of necessary progression. I can’t deny that it became superfluous in a way and certainly over-indulgent, but we had a great little run of albums for a moment there.

Gary – You’re a bit older than me but we had the same thing generationally – your ‘80s fans would probably put you in that bag without realising you grew up with a whole other bunch of stuff.

Tom – It’s like Viv Albertine (The Slits) saying her first concert was Edgar Broughton. I was guilty of seeing her as a punk girl and I thought nothing could have existed until that point where she heard The Clash or something. It’s absurd, of course.

JOHAN SEBASTIAN BACH – CONCERTO NO. 1 (Album: The Brandenburg Concertos)

Tom – This is the Brandenburg’s but quite an old recording, I think.

Gary – You actually bought it for me, when you were still living here. Because we discussed Bach and I asked for your recommendations.

Tom – The thing about the Brandenburg’s – one of the high points of polyphonic baroque consort music – it’s all happy music. Where so much of Bach is profoundly passionate and disturbed, but he was obviously in a good mood when he wrote this. But unfortunately that means it’s the kind of thing that gets played in gift shops at Christmas-time to put people in a happy spending mood.

Gary – You’ve got to find a way in to listening to it that goes beyond that. As far as the classical canon is concerned, Bach is your main man?

Tom – Yes. And the reason is because he kind of wrote the rule book on not only form and style but on the way notes go together. And that’s all we really have in the Western tradition is a series of experiments about how notes go together. He kind of ditched melody as a surface element, that’s all it’s become, and rhythm is as square as it gets compared to other cultures, but what we do have is this internal architecture of polyphony, lots of different notes working together, forming tensions and releases, and he not only wrote – and it’s partly coincidence, he happened to be the genius alive at the time when for a start keyboards started being tuned in equal temperament so you could actually play modulating complex music like that.

Gary – What did they have before that?

Tom – Well, before baroque you had early music, which is essentially no modulating, it could only go up a fourth or a fifth or down a fourth or a fifth, couldn’t make these wonderful harmonic modulations. And it’s because in order to modulate fully into any different key you’ve got to have a compromise of tuning, otherwise if you tune it perfectly in one key it’s going to sound sour in another. So how do you make that compromise? It’s the same as a guitar neck. In turn that leads to certain kinds of music being made. I don’t know if you’ve ever played a guitar but you find that it’s fine down here then you move up the neck and it all goes weird. [laughs] Because they haven’t got the compromise of the fretting correct. So you simply have to play in one or two different keys that a guitar says you can play it in.

Let me have a look at the cover. Number 3 is the killer. And that’s the one that Keith Emerson took, but it’s the Third Movement of number 3, that’s the most enlightening. And it also includes a fantastically revolutionary idea, the second movement of the third Brandenburg, he writes a two chord cadence, and basically says you can do anything you want as long as it ends up like that. Can you imagine in the time – if you or I or Frank Zappa said that we’d go ‘far out, man!’ but back then it was an outrageous idea!

EBERHARD WEBER – MORE COLOURS (Album: The Colours Of Chloe, 1973)

Tom – [on the first note] Eberhard Weber. Sounds like the The Colours Of Chloe. This calls back to almost a primeval intelligence. This to me speaks of the fundamental melancholy of being a human being, what it is to be human, to understand that basically we all return to shit. It’s the sadness of the condition that’s reflected in this music. And yet it’s haunting and beautiful at the same time. As you know he’s one of my all-time heroes.

Gary – When did you first hear him?

Tom – College days, I think. I tell you who was big: Keith Jarrett. The Koln Concert, along with Neil Young’s After The Goldrush and Leonard Cohen. We used to get stoned and listen to The Koln Concert. And that introduced me to the ECM catalogue and European jazz. I think I probably discovered him after moving to Bath… this record and very soon after that my favourite of his, The Following Morning. Have you watched him on YouTube at all? There are some staggering performances. But what interested me was that some of these things that you thought were improvised were actually, he does them note for note. So he’s obviously a very strict and controlled compositionalist, not just letting it hang on the wing.

Gary – The ethos of ‘70s ECM label is really fascinating. It doesn’t get talked about a lot. ECM have dished out a lot of lavish books and things but they’ve just been record covers and photographs; there’s not a lot of writing about it.

Gary – The ethos of ‘70s ECM label is really fascinating. It doesn’t get talked about a lot. ECM have dished out a lot of lavish books and things but they’ve just been record covers and photographs; there’s not a lot of writing about it.

Tom – I think it’s un-competitive. One of the nice things is that they’re just doing their own thing, they’re not trying to fit in.

Gary – It’s jazz influenced but you couldn’t say it’s post-Coltrane, could you?

Tom – Ohhhh… there’s a track on here called ‘An Evening With Vincent Van Ritz’ which is jazz, but that never interested me, it was this stuff, this atmospheric merging of what I thought was improvisational jazz with orchestral textures. Absolutely beautiful. Never got to see him live, although I’ve seen most of his band members in various guises. And it was realising that I’d kind of bungled that that made me record those tributes.

Gary – Are you going to release those?

Tom – They’re kind of too unfinished. I did it in two or three days, and listening back I think there are great ideas in there but it would need serious work. I like this guy Rainer Bruninghaus, the pianist. He’s also worth following, and I saw him play with Jan Garbarek, which was a concert so pungent it almost drove me out, but I stayed just because I was enjoying the keyboard so much.

Gary – What was wrong with it?

Tom – It was a seated auditorium so we were stuck… we couldn’t shift and we were right in front of the speakers and there was this honking mid-range nastiness, very, very loud. Under normal circumstances I would have beaten a retreat but…

TALVIN SINGH – ONE (Album: Ha! 2001)

Tom – Is it something like Tabla Beat Science? Don’t know who it is, it could be Nitin Sawhney or someone like that.

Gary – Close. He played a lot of sessions.

T – It’ll come to me, though. The tabla player from Massive Attack?

G – Yes, it’s Talvin Singh. Obviously it’s an Indo-fusion project, and that’s something you’ve been involved with as well. And obviously India is a place of deep significance to you. Does the interest in Indian music come out of that, or is it the other way around?

Tom – It probably starts with the Beatles fiddling around with… having Indian instruments on ‘Norwegian Wood’ and Sergeant Pepper. Those kind of things were present in my teenage cultural context, and it was probably trendy to start aping hippy travellers with long hair and beads, which they got from India, so without realising it you’ve got one foot in the door anyway. But it was when I was at college that Indian mysticism and philosophy became a dramatic eye opener to me, it was another way of looking at reality, and particularly one that didn’t involve drugs, because I was looking for a way out of that. There was still an exciting inner journey to be made that didn’t involve getting wasted. So very exciting. And it was all corny stuff like ‘Be Here Now’ by Baba Ram Dass and the Californian hippy philosophers, which leads one to the thought that India is the place that all this stuff has come out of so it might be worth checking out. And then of course there was an Indian presence culturally in the UK, there was Indian food and Indian clothes and so forth, so it’s not that extraordinary to have made that leap.

Gary – I remember seeing a thing on Ravi Shankar on how he’d been to Hollywood in the 1940s and had a huge impact on musical soundtracks.

Tom – That surprises me, but sometimes in biographies you write the script and they make up the facts to fit.

Gary – I don’t know if you’ve read Donovan’s autobiography.

Tom – No, but I’d like to.

Gary – He created world music fusion.

Tom – Oh, of course he did! Although I do know a guy who made a film about Donovan when he was at the height of his hippy success and living in a yacht in the Aegean somewhere with scantily clad women in every direction. And this guy was using a Super 8 to capture it all, sitting on a boat, and in between long sessions of steamy sex he’d pick up a 12-string. He also dabbled with the Eastern philosophy.

Gary – Actually, he was on that Beatles trip with the Maharishi.

Tom – He was. And interestingly enough part of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi ashram in a place just out of Rishikesh was abandoned for years, and now it’s found a new lease of life as ‘Beatles were here’. Just a few hippies knew about that so there’s lots of graffiti, you know, and it’s a weird backwood experience to go there and see it and ‘this is where the Beatles were’.

Gary – How did you settle yourself on a way of making Indo-fusion? I presume you’re a bit of a fan of classical Indian music?

Tom – Yes, although I’m a very lazy student so… with the Thompson Twins the exciting thing for me was that music could be community based. And I didn’t like that at that at that time people just sat and watched four-piece rock bands. I thought that they should be joining in. In that physical situation everyone should have the potential to join in, sing along, bash an instrument. So that’s how we started handing out percussion instruments to the audience and getting participation from an audience. I remember feeling very strongly that our culture had lost that ability for music to be a collective, and therefore it didn’t mean anything, it was just an entertainment that you watched and listened to. And the songs that people sang around the cooking fires in Africa were fundamentally more important than the ones you would see on Top Of The Pops, which were fundamentally meaningless. But that was my rather lofty ambition, and it was an African one for me, and I was covering Sierra Leones boat songs and things like that. And then when I got my hands on the studio I thought an Indian thing would sound good, and I was almost too embarrassed to admit it but I was sneaking them into pop songs, sometimes more blatantly than others – getting a couple of tabla players involved or pretending to sing a raga based scale rather than the Western one. Dilettante style indulgences.

NONPLACE URBAN FIELD – PAN 13 (Album: Golden Star, 1996)

Tom – This sounds like Muslimgauze. Is it Burnt [Friedman]? I don’t know which one…

Gary – Golden Star.

Tom – This is a fabulous record.

TWENTY SIXTY SIX AND THEN – THE BUTTER KING (Album: Reflections, 1972)

Tom – I don’t know this. I imagine it’s some obscure King Crimson copy or something. I have to ask, what on earth made you play this to me?

Gary – Because it’s so ridiculous, and over the years we’ve had so much fun with ridiculous stuff. I don’t know many musicians who have enough levity to be able to appreciate silly stuff. For instance, things like Florence Foster Jenkins, Wing, and that anonymous CD of what must have been the worst singer ever. I love the preposterousness of this song.

Tom – To me, this is just like so many other bands of the era.

TOMITA – SNOWFLAKES ARE DANCING (Album: Snowflakes Are Dancing, 1974)

Tom – I don’t recognise this but I love it. Is this the Japanese snowflake guy?

Gary – He’s got a very interesting background, this guy. Do you remember Kimba The White Lion, the cartoon series, from the mid-‘60s. We saw a version of it that had the American soundtrack but the original Japanese soundtrack was by this guy, Isao Tomita. So he was writing music for cartoons before his stellar career as a synthesist.

Tom – I love it.

* Thanks to Terry Humphries at Audio Reference for allowing us to sit and audition music and natter for hours at his showroom. Audio Reference is at 2/25A Lake Road, Devonport, Auckland. Gear used that day included:

1) Accustic Arts TOP PLAYER – I Mk3 CD Player w/ 24/192 upsample DAC – @ RRP $9995

2) AQUA La Scala MkII Reference tube DAC 24/192 R2R ladder DAC USB RCA XLR etc @ RRP $8250.

3) DarTZeel LHC-208 Danalogue Streaming 200w Integrated amp 24/385 PCM 2xDSD DAC @ RRP $20,995

4) UBIQ AUDIO Model-One floorstanders 38mm tweeter 8″ mid 12″ bass paper drivers @ RRP $18,995/pr

5) Acoustic Zen Absolute Silver interconnects XLR-zero crystal ribbon silver – 1m @ RRP $4750/pr

6) TELLURIUM – Q Speaker cable Silver Diamond master reference banana/banana – 3mtr @ RRP $11,995/pr

Note: As this listening session took place some time back, some of this gear may not still be available.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9694K85Xc8

Brilliant Read *(@_9)*