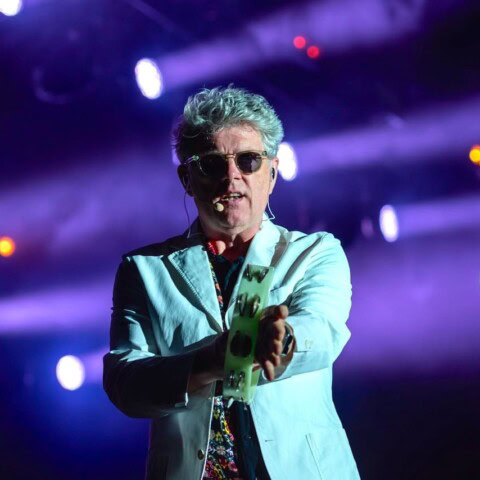

GARY STEEL is celebrating 40 years of music journalism by disintering and re-animating interviews and reviews from his fat archive. To honour the publication of Shayne Carter’s memoir, Dead People I Have Known, here’s Gazza’s 2001 profile on one of NZ’s greatest rock gods.

SHAYNE Carter still has a sneer in his voice. The same voice that sneered persuasively through the bracing racket of Straitjacket Fits records, the group that should have made Shayne Carter the first bona fide Kiwi rock star on the international stage.

It almost happened, but Carter is sitting here today with his sneer because it all went horribly wrong back in ’94, and because, after all this time, NZ’s greatest rock icon is returning to fulfill a contractual obligation: the creative obligation of his resuscitated muse.

Carter’s muse brought him up screaming from Dunedin and the Flying Nun zeitgeist of the ’80s, where his post-punk outfit Straitjacket Fits first trashed the local scene, before turning its attentions to bigger markets.

“You end up sitting in people’s offices, talking to them, and you don’t like them, and you don’t like what they’re saying.”

The spectacular rollercoaster ride of ‘She Speeds’ birthed a new rock god. Shayne P. Carter, with his classic idol cheekbones and youthful defiance, was an instant icon in a country woefully lacking in sex appeal.

London called and Straitjacket Fits came running, whipping up feverish music press and rapturish fan flurries; in America, a major label snapped them up and set them to work.

Then the facade began to crumble.

“The industry is a shitty place, and you get to the epicentre and you think ‘What’s this got to do with what propels me to pick up my guitar and write music?’ Bugger all. You end up sitting in people’s offices, talking to them, and you don’t like them, and you don’t like what they’re saying. There’s lots of dodgy characters in the industry and lots of bullshitters…

“You get to the point where you’re in a band and they’re quite high profile in the industry, and all this peripheral stuff becomes important, and it’s not important. The important thing is loving music and being moved by it, because that’s the only way you can create music yourself that moves you, and if it moves you it will move other people.”

IT’S a sweat-soaked February day and it’s a blessing to get out of town. Shayne Carter has invited the hack to his temporary digs at Langholm, on Auckland’s West Coast, at the sometime residence of the man who got him to sign that Sony contract two years ago, label manager Malcolm Black. The plan: today, Carter will unveil the long-awaited album by his group, Dimmer, and consent to an interview.

First, we sun ourselves in the backyard, perched on the lip of an ancient Maori pa site, which runs spectacularly past strands of native bush down to a vista of Manukau harbour. We discuss mutual health concerns and some of the burning issues for today’s sensitive thirtysomethings. Like, how to stay angry and use naturopathic medicines. Carter finishes the conversation by extolling the benefits of meditation. With a sneer.

“I’d fucken love some peace and tranquility man. After a while it’s too much effort, too painful, and you just want some fucken peace and quiet.”

“I’d fucken love some peace and tranquility man. Fucken hell. I think as you get older, that’s all you actually want. When you’re younger you experiment and you want to do dangerous things. But after a while it’s too much effort, too painful, and you just want some fucken peace and quiet.”

It’s been a painful few months. Having just about put the finishing touches to his record late last year, Carter’s Dad suddenly died, too young in his 50s, and everything changed. At times, the album seemed a tortuous process that was never going to see completion. But this news blew everything out of the water. With his own health issues and relationship complications adding to a volatile mixture, Carter couldn’t have felt less like starting on the whole tedious task of promoting his first album in seven years.

Retiring to the lounge, I’m graced with two plays of the long-awaited album, I Believe You Are A Star, but I’m told to commit it to memory. No taking this CD home.

Edgily, Carter suggests we postpone the interview and head for town to catch a movie, Hidden Dragon, Crouching Tiger.

FOR a physically imposing guy – Shayne looks and acts tough – Carter is the biggest wuss I’ve met. When the writer drove Carter and his girlfriend to an electronic event at Titirangi a couple of years ago, he wanted to leave almost immediately, citing certain imminent death resulting from the bites of a battalion of mosquitos. It was the perfect black comedy, Carter was so out of his element. Like many kids whose teenage years coincided with the post-punk era of the early ’80s, Shayne Carter holds on to elements of his punk roots, noticeably an avowed cynicism, and a hatred for the woolly ways of the hippy scum. Titirangi had mosquitos and hippies, in spades, soaking in their patchouli oil, fire-eating and blissing out in the West Coast mud. Carter couldn’t wait to get out of there.

But this is part of what makes him such a great musical presence: in everything he’s ever done – and that means some of the best pop songs ever committed to the recorded medium in this part of the world – Carter manfully wrestles between his overt sensitivity and his other side, a kind of angsty malevolence.

“I’m quite an anxious person, so that anxiety comes through in my music.”

In Straitjacket Fits, roaring malevolence rules, but on the new record, the slightly mellower, 36-year-old Carter has found some kind of balance between angst and beauty and that wonderful, picaresque, inbetween state, melancholy.

“I’m quite an anxious person, so that anxiety comes through in my music. I like music that has tension and is spooky, almost a mood of anxiety, kind of like melancholy, a beautifully bleak feeling. You know how melancholy is kind of delicious, as well as sad?

“But I think it’s a beautiful record. It’s not trying to prove how tough it is. It’s got quite a few girly bits on it, the (falsetto) singing, and I wasn’t scared to do that. I wanted to make a beautiful record, so in lots of ways it’s quite feminine. It’s the music I wanted to make, one that was timeless and didn’t sound like it was super contemporary. It sounds slightly out of its time, it doesn’t totally fit in with what’s going on, and I think that’s a strength, a good thing.

“If it feels real no-one else can touch it because it’s true, you know? And that’s always been my criteria, whether that piece of music feels real to me or not. It’s soul, that’s the only way I can describe it. All my favourite music has got that soul and truth to it.”

WHEN Straitjacket Fits came to a grinding halt in 1994, Shayne Carter retreated to Dunedin for a couple of years. Feeling embittered by the industry that promotes art for money, but so often stalls the creative process, Carter retreated to the city he grew up in, and set about rejecting every musical value he had previously subscribed to.

“The band had been going for seven or eight years, and a band’s like a gang, and eventually you tire of that, running round with the same bunch of boys. And with any kind of creative entity, there’s only so much water in the well. And by the end of it I was feeling quite frustrated, I felt like I carried it, and I couldn’t be bothered doing that anymore.

“I just felt a bit dirty and sullied by the end of the Straitjackets, and I just needed to go back to where I came from, and learn to love music again.”

“I just felt a bit dirty and sullied by the end of the Straitjackets, possibly slightly disillusioned with the whole thing, and I just needed to go back to where I came from, and learn to love music again.

“I’ve had to completely relearn my whole way of making music. I’ve always written songs in a practice room with a band, and I tired of that. I spent two years in Dunedin just jamming, doing a lot of free-form stuff, and didn’t write a concrete song for about two years. I got sick of the rock thing.”

BUT the story of the making of I Believe You Are A Star is set squarely in Auckland, a city that Carter still finds dislocated, remote and devoid of the nurturing community qualities of Dunedin. Relocating to the Queen city in 1996, Carter set about the long process of recalibrating his musical orientation. Becoming another of those flatting fringe denizens bordering Ponsonby and Grey Lynn, he formed the three-piece Dimmer and released a tentative EP through his old company, Flying Nun. But never really musically a part of the strumming, drone folk-rock of the Flying Nun stable, and sensing the strong arm of big business bearing down on the label (Flying Nun is now part of the Festival-Mushroom group, owned by media tycoon Rupert Murdoch), Carter felt increasingly alienated by the company that had formerly espoused such a tight-knit, homely approach to music-making. Suspended in a city with all the star-making machinery, but none of the creative mechanisms he was used to, Shayne Carter slowly began his agonising, man-alone voyage back to a place that felt right.

This meant a misjudged solo guitar frenzy in an Auckland club, and a clutch of Dimmer performances that were more freeform psychedelic wig-outs than hints of any intrinsic Carteresque qualities.

It was starting to seem like Dim and Dimmer.

“Sometimes I think that in this town (Auckland) the apex of creativity is making a good Toyota ad, and that’s not very inspiring.”

“Auckland is all about money, and to generate money you have to appeal to a wider public spectrum, and to appeal to a wider public spectrum, your product has to be blander. Sometimes I think that in this town the apex of creativity is making a good Toyota ad, and that’s not very inspiring. In Dunedin, your poor friend who’s sitting on the dole but has got these amazing artistic ideas will sit you down and give you a great book to read or… I hate poetry but they’ll read you a great fucking poem. I don’t find Auckland a creative or inspiring town at all.

“I do like the climate!

“Everyone needs some form of recognition or encouragement, and when you’re dealing with the kind of thing that I do, it’s all created in isolation, and you don’t get anything like that back until you finish it.

Still looking for his muse, Carter found his investigation of the new areas of computer-driven electronic music rewarding.

“When I first heard that stuff I thought ‘this is the brave new music’. It’s taking risks, and it’s doing all the things I was finding lacking in rock music at the time: intrigue, mystery, people trying things that I hadn’t heard before. I found that really inspiring, and I had to educate myself with that kind of music. And then I went through all the politics of it as well. I thought it was really great not to have a singer up there going ‘me me me’. I liked the whole socialistic principle of it, that the audience was just as important as the music. Then I went back and investigated all the music from where electronic music stemmed from. Brian Eno’s ambient stuff, Kraftwerk and all that kind of stuff.

“For a long time I thought singing and and playing songs was really square, so I didn’t do it, I just wrote instrumentals. But then I went full circle. I got sick of the vague, unspecific nature of the electronic thing. I’ve had big trips on Marvin Gaye, and that Careless Love book on Elvis (by Peter Guralnick) totally brought me back to songs and singing. I thought ‘fuck, you can’t beat a great tune’. That’s a really human thing, to want to hear someone sing, and I realised that’s what I can do. I’m a guitar player who can sing and write songs. So I started doing that again, but I applied everything I’d learnt in the last few years.”

“Making this record at times has been a real struggle. Getting no feedback or anything to sustain you apart from your own self-belief.”

As tortuous as the process was, Carter made the creative isolation of Auckland work to his advantage. Inking his deal with Sony, which allows for complete creative control, Carter began to get together the gear he needed for a new working methodology; getting to grips with new computer-based technology, he worked mostly alone, with Gary Sullivan providing drum tracks for his fledgling creations.

“Making this record at times has been a real struggle. To hold onto your belief when you’re operating in a vacuum, getting no feedback or anything to sustain you apart from your own self-belief. It’s a hard road to hoe, and lots of times I’d sit there with no money and the beginnings of this record that’s taken forever to make… it tests your spirit and your belief, and I’m really proud I’ve held onto it and sustained myself to the point that I’ve done it. I had points where I just wanted to give up, but I thought how ridiculous it would seem 10 years down the track if I hadn’t made this record. It was something I had to do, and that’s what sustained me through it all.”

HAVING creative control means Carter has been allowed to conceptualise the video clips. For the first Sony single, ‘Evolution’, he devised a video based on the Elvis 1968 comeback TV special, featuring himself as a boy, a young man, and a middle-aged man. The middle-aged Carter was his father.

“My Dad described the video shoot as tense and demanding, but he loved it. Dad didn’t have a lot of money or anything, so it was really great to be able to bring him up to Auckland. Being a brown guy in the South Island, there’s not a lot of brown people wandering around down there, so he really loved all the brown people wandering around K’rd… he spent two days just wandering up and down and saying ‘ki ora’ to everyone! The thing was, everyone went ‘ki ora’ back, so it was really cool. Just goes to show what you give out you get back.

“He was really proud, loved the music, even the really wiggy shit. He loved the ‘Crystallator’ single… when I gave it to him he really flipped out, and said ‘I can hear Scottish music, I can hear Maori music, I can hear all these different things!'”

Carter’s parents were both musicians, his mother Caucasian, his father Maori. But Carter Jnr grew up in a white man’s world, scarcely aware of his Maori heritage; neither did his dad. He was adopted.

Straitjacket Fits, and Carter’s earlier groups Bored Games and the Double Happys, were both resolutely white-sounding.

“You don’t get anything heavier than your Dad dying, and it has put the album and all this business a bit lower on the totem pole.”

“There’s always a big deal made about how Flying Nun music didn’t have any r’n’b inflections, and that’s really true. But at the same time I have always loved black music; stuff like Muddy Waters, Sly Stone, Otis Redding. And Hendrix has always been one of my favourites.

“There are a lot of black music inflections on this record. That’s what I love about hip-hop, the irresistibility of that beat, no matter what you start nodding your head, and it’s music that plugs into those primal pulses.”

In October, a bombshell. Slaving away and over deadline on the album, Carter got word that his Dad had died. It has sent his whole world reeling.

“You don’t get anything heavier than your Dad dying. That’s about as heavy as it gets really. And to a certain extent it has put the album and all this business a bit lower on the totem pole.”

At his Dad’s tangi, Carter realised that there was a whole world – his heritage – that he knew nothing about.

“He was a Maori guy who was adopted and brought up by Europeans, so my contact with the culture has been really limited. But in the contact I have had, there are all these amazing things you get in Maori culture that you just don’t get in European culture, and it’s a culture that’s not about the self. European culture is all about me-me-me and that’s why there are so many lonely people in capitalistic systems. Whereas in that system it’s about your whanau and even about your relatives who are dead, and where you come from, and all the parts that have made you who and what you are. I was really struck at the tangi by the spirituality of it, and it’s a really important part of me that I have not explored enough. And I really want to explore it, because it’s a part of who I am. Being a musician, that is part of my Maoriness coming through. It’s hard to qualify that, but it’s something I’ve felt. It’s a very spiritual culture and music’s a very spiritual thing. It’s not something I do to make money, or to get my photograph in magazines, it’s deeper than that. I really believe that there’s a connection there. It’s so unique and so powerful.”

“Like a lot of adopted people, Dad got rebuffed somewhere along the line and he was trying to find out but he never did.”

More news to rock Carter’s world:

“We just found out where our family comes from. Like a lot of adopted people, Dad got rebuffed somewhere along the line and he was trying to find out but he never did. It effected him in that where you come from and your identity is such an important part of it and if you haven’t got that, you’re missing such a big part. But we’ve found out where our family comes from, and we’re actually going to meet those people this year, so it will be amazing.”

THERE is an air of tragedy around the demise of Straitjacket Fits. Most bands have one crack at the big time. Carter’s moment came and went and without breaking through to deserved success in those crucial international markets. Now in his mid-30s, there is a vague residue of what could have been, but the artist in Carter has determined a future that looks more underground than hitbound.

“You can’t feel regretful about that kind of stuff, because that’s just the way it is. I’m proud of what that band did, but I want to do something different, and it’s taken me this length of time to solidify what I really wanted to do. I could have released four okay records in this period, but I wasn’t going to let it go until I had something that said what I wanted to say and did it the way I wanted to do it. There’s enough pointless and mediocre music out there without me contributing to it.”

Whether Carter’s moment in the spotlight has come and gone is a moot point. What matters is that I Believe You Are A Star is a great record, possibly one of the most original, daring and outrageously well-defined pieces of musical art to have emanated from this country.

“There’s enough pointless and mediocre music out there without me contributing to it.”

There are no obvious pop songs or radio hits, so Carter will be looking to find his audience through the underground network of music fans around the world who have become more apparent since the advent of the internet: if anyone has any doubts about the level of interest in Shayne Carter seven years after his big group broke up, just try trawling through all the slathering fan websites!

“I wasn’t going to let it go until it was right. I really enjoyed the attention to detail, shaping that whole aesthetic. I wanted to write all the songs in one or two notes. That’s a big challenge. As a songwriter you start off all naive and you play really simple songs because that’s all you know. And then you make it more complicated because you want to keep it interesting for yourself. It’s a huge challenge to write one or two notes without it getting boring. I got into the concept of inverse power, where instead of hitting a certain point and going up, it goes down; where there should be a power chord, there’s nothing. I also got into quiet songs… playing quiet and subtle songs, but it’s still really powerful. It’s a different kind of tension, and a different kind of power.

“Gary (Sullivan) cut out these letters that said ‘GONE’, and that wooden carving sat in the studio the whole time, and we just wanted to get a really woozy vibe to the whole record. ‘GONE’, you know?

“All the lyrics on this record a really strong. I worked really hard to make every line mean something, so that it wasn’t throwaway, or a copout. No matter how obtuse it is to your average listener, all the lyrics on the record really stand up. I think it’s cool that people listen to rock songs and get the lyrics wrong, but it doesn’t matter, because they still believe they know what the song’s about, they have their own interpretation of it. So with lots of my lyrics I do make them quite ambiguous, so you can take them any number of ways.

WE finally get to sit down and talk at my place. Despite his reticence, Carter is an adept interviewee. Certainly, he’s aware of the process, having started his professional life as a cub reporter. Unlike the many artists whose interests barely extend from their own monomaniacal tunnel vision, Carter is ferociously intelligent, keenly curious, and blindingly well-versed in the whole mythology of music stardom, and pop culture in general. A voracious reader of biographies, a fan at heart, this candidate for the elite of rock legend must get a strange chill when he tallies up the almost uniformly tragic lives of his heroes Elvis Presley, John Lennon, Marvin Gaye and others.

“It’s a wank and a cliche, but out of pain comes great art. It’s the comedy is tragedy thing, too. So many great comedians are actually really sad people, whether it’s someone like Spike Milligan or Richard Pryor. Yeah I quite often laugh, but I’m often laughing at the blackness of it all. It’s the same thing with this live performance of Pryor…. all this funny shit, but at the same time you can see the pain on his face as he’s saying it, because it’s actually truly hurtful stuff.

“I laugh at the absurdity of it all and people running around doing the stupid things that humans do. Sometimes all you can do is laugh…

“I’m a fan though. It goes back to loving it. Great fiction is supposed to reveal things about the human condition, and express and arrive at quintessential human truths. But all those truths are there in people’s lives anyway, which is why I like reading about people who’ve actually lived. And you come to the same conclusions about what it’s all about when you read about people’s lives. The fuckups they made and the triumphs they had. So I suppose I am fascinated by that, and I suppose I am fascinated by icons to a certain extent, too. But it just goes back to being a fan, and people are interesting, especially people who’ve done great things.”

In the end, music for Shayne Carter means the same thing as the peak moments of sporting achievement: transcendence.

“I actually really enjoy playing football, I find it very Zen, because everything falls away and you’re just concentrating on that ball. I find it a great release.

“I laugh at the absurdity of it all and people running around doing the stupid things that humans do.”

“As a child I used to sit inside on really hot days and watch sport and get headaches, and Mum would say, ‘Shayne go out and play’ and I’d say, ‘I can’t Mum there’s sport on TV. Have you got any Disprin?’

“In a lifetime you spend so much time tripping over your own feet, that those Zen moments are perfect balance, they’re to be savoured. Whether it’s doing something really great with a soccer ball, or coming up with this beautifully balanced, symmetrical piece of music, those moments are fleeting, but they’re the ones that are worthwhile. The rest is just stumbling around.

“If somebody watches a great performer on the sports field, they’re getting the same buzz from that as a lot of people get from a great piece of music.”

“Music is one of the few transcendent things in life. Music has always effected me powerfully, in the same way that a great book or a great movie will. You watch The Straight Story (David Lynch) and you get the same feeling from that as listening to a great piece of music. But if somebody watches a great performer on the sports field, they’re getting the same buzz from that as a lot of people get from a great piece of music. They’re seeing human transcendence of the ordinary, seeing human achievement. So if you watch Michael Jordan playing basketball, it’s this form of expression that is very similar to music. I can watch Jordan play and I’ll get the same buzz as listening to Marvin Gaye sing. It’s just human excellence in performance, and it’s inspiring. The possibilities of humans, and about the beautiful things humans can do, whether it’s a piece of music or this great piece of athletic prowess.”

- I Believe You Are A Star was released early May 2001 on Sony.

- Shayne’s memoir, Dead People I Have Known, is published by Victoria University press and available here.