GARY STEEL is celebrating 40 years of music journalism by disintering and re-animating interviews and reviews from his fat archive. In this piece, he meets the mastermind behind the 1978 musical version of War Of The Worlds, Jeff Wayne, on the occasion of its 2005 reissue.

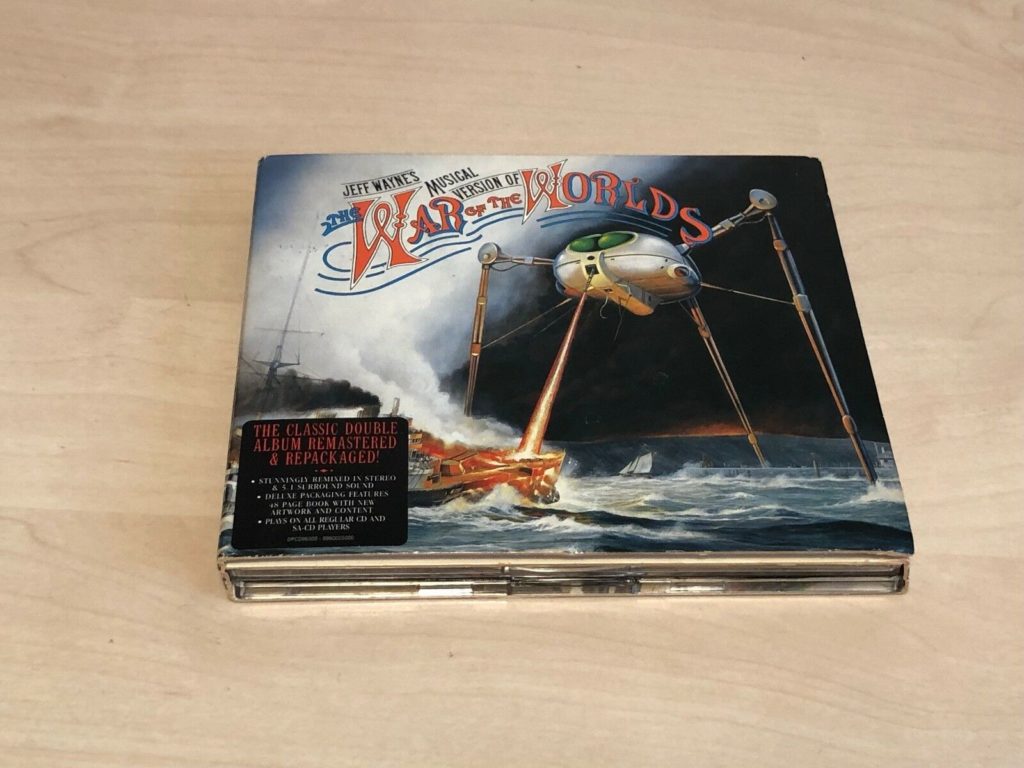

Who doesn’t remember hearing The War Of The Worlds? Not that liberty-taking Americanisation of HG Wells’ prototypically Victorian-English sci-fi tale starring Tom Cruise and all that. No, we’re talking about Waynes World – that’s Jeff Wayne’s The War Of The Worlds, that splendidly garish yet somehow utterly compelling 1978 near-masterpiece of a double album.

Who doesn’t remember hearing The War Of The Worlds? Not that liberty-taking Americanisation of HG Wells’ prototypically Victorian-English sci-fi tale starring Tom Cruise and all that. No, we’re talking about Waynes World – that’s Jeff Wayne’s The War Of The Worlds, that splendidly garish yet somehow utterly compelling 1978 near-masterpiece of a double album.

Well, there can’t be many out there who haven’t come across this humdinger over the years. A massive hit at the time, it’s continued to sell in huge numbers over the years, and tracks from the album have generated no fewer than 300 DJ remixes.

This story-song phenomenon, with the late Richard Burton narrating the tale of Martian menace, and a truly amazing core cast of key musos and vocal guest stars, has just gone and got a makeover.

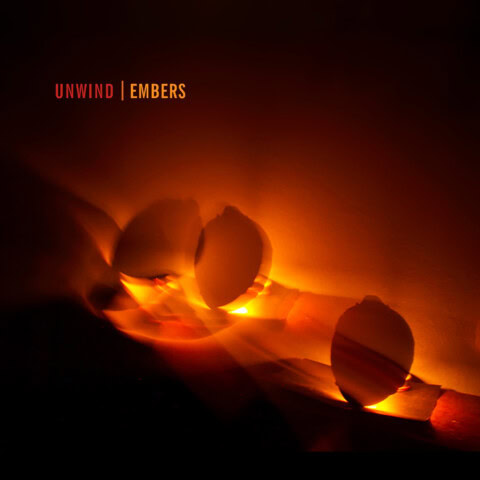

In a move totally unrelated and coincidental to Spielberg’s bloated opus, Jeff Wayne’s The War Of The Worlds has been remixed, remastered, and turned into a stunning 5.1 piece of audio wonderment for today’s listeners.

In addition to the double SACD (which can play in both remastered stereo and 5.1 surround sound versions, depending on your equipment), there’s also a seven disc box set, and early next year, the album will get the big live stage treatment.

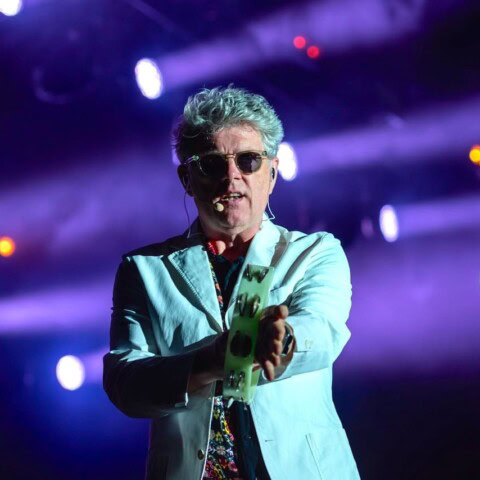

But who is this Jeff Wayne chap? And how come he gets to have his name in lights right before the title? I met Jeff Wayne on a brief promotional stop-over in New Zealand, where I got to find out about this under-sung character, and quiz him both about the making of the original album, and the newfangled version.

A well-preserved 62, Wayne is a gracious interview subject, and very happy to wax enthusiastic about an album that must have seemed like a monkey on his back at certain times since its release 27 years ago. It turns out he’s been to New Zealand just once before… 27 years before, in fact, to promote the original release of Jeff Wayne’s The War Of The Worlds!

“It was a hugely complex task to reassemble the deteriorating master tapes”

The original idea, it transpires, was to reissue the album for its 25th anniversary, but the project kept getting more ambitious, and it ate up three years in preparation. Why so long? In a nutshell, it was a hugely complex task to reassemble the deteriorating master tapes, and that’s just the beginning of it.

“It was quite a large team,” says Wayne. “We went back to the stereo tapes, the multi-track tapes, and because they were all in analogue, the first thing we had to do was to bake all 77 multi-track tapes. The truth was that even when we finished the original War Of The Worlds, because it had taken almost three years to produce, the oxide on the tape had started to wear out. So the top frequencies, like the crack of a snare drum, was more like a ‘phhhp’, rather than a real ‘crack!’ So the baking process was the real starting point, and the device called the Maglink which was the first device to link two multi-track tape machines together, had long disappeared technologically. So we couldn’t even play it in 48 track. It was the first 48 track production, and it was just coincidental that the studio I produced and recorded War Of The Worlds in had a distribution company, and they’d just taken delivery of this thing from the United States, the Maglink, linked by a code to two 24 track machines.

“Even when we finished the original War Of The Worlds, because it had taken almost three years to produce, the oxide on the tape had started to wear out.”

“The format of the day was 16 or 24 track tape. So I was both a guinea pig and the benefactor of this new ability to do stuff you couldn’t do before. And looking back at it, if I hadn’t had 48 tracks, War Of The Worlds would have turned into something quite different, because I would have been so limited to what I could record that it would have been a different sound and a different scale of production. So that opened tremendous creative possibilities.

“But jumping forward to today, the first thing we did was bake the tapes, and it was all remixed in my studio, and I’ve got a really good digital studio with surround sound and everything. A gentleman that works with me as a programmer, it took him about three months, because we couldn’t listen to all 48 tracks, he had to first dump all 77 multi-track tapes into the digital domain, and then rebuild it track by track, sound by sound, and then synchronise it manually, listening to the original double album. I think he was either nuts trying to have a go at it, or is now nuts having attempted and succeeded in fact! So that once that was done, it was edited to the shape that the double album became, because my first assembly on the multi-track tapes was just over two hours in length. Whereas it became a 96-minute work, so there was a lot of material that was cut down.

“But jumping forward to today, the first thing we did was bake the tapes, and it was all remixed in my studio, and I’ve got a really good digital studio with surround sound and everything. A gentleman that works with me as a programmer, it took him about three months, because we couldn’t listen to all 48 tracks, he had to first dump all 77 multi-track tapes into the digital domain, and then rebuild it track by track, sound by sound, and then synchronise it manually, listening to the original double album. I think he was either nuts trying to have a go at it, or is now nuts having attempted and succeeded in fact! So that once that was done, it was edited to the shape that the double album became, because my first assembly on the multi-track tapes was just over two hours in length. Whereas it became a 96-minute work, so there was a lot of material that was cut down.

“We were working creatively with 46 tracks. But each track had between four and seven different sounds on it, with different EQ’s and echoes and all that, so it was hundreds and hundreds of sounds. And in thinking back to the first time we mixed it in the ‘70s, it was in very small segments, because the sounds kept changing so dramatically we’d have to set it up. Whereas now in digital you can assign each sound to its own channel with its own effect, or whatever you want to do. So now we’ve got a new stereo mix, and when you listen to it in comparison with the CD and the original vinyl, it’s much punchier, more clear, you can hear sounds individually that you could never hear on the original stereo… you could feel them but you couldn’t hear them. And the punches, it’s really precise, it’s great. And surround sound is its own thing, which didn’t exist in the ‘70s, and it’s a wonderful medium. I produced it with our engineer and programmer, with a real idea of what we wanted to do to it. Really to surround you, not just to use the back speakers for ambience. So it’s a real 360 degrees use of the audio palette.”

When Wayne set out to remaster his one (epic) hit wonder, he already owned a fabulous studio, but it wasn’t yet equipped with surround sound gear. So he went out and did his research, and got the best system he could lay his hands on.

When Wayne set out to remaster his one (epic) hit wonder, he already owned a fabulous studio, but it wasn’t yet equipped with surround sound gear. So he went out and did his research, and got the best system he could lay his hands on.

Was there anything about the original album that he didn’t like, and couldn’t resist making sneaky changes to when it came to the new mix?

“Not on the stereo mix, but on the surround sound mix, there were some sound effects that I had recorded and just chickened out on using the first time round, and I put those back in. One was an owl called Ozzy which hoots in time to the bass guitar on a track called The Artillery Man Of The Fighting Machine, and there’s some rifle and canon fire. There’s a track called Horsell Common & The Heat Ray where you hear a cylinder unscrewing, and that’s an effect we designed ourselves.

“In comparison with the original vinyl, it’s much punchier, more clear, you can hear sounds individually that you could never hear”

“If I was doing it today,” he adds, “I think I’d be most conscious of the fact that two or three of the tracks I scored out as an arranger separate to my compositions, to have the drummers playing the disco beat of the day. Today would be different, maybe hip-hop or breakbeat or something like that. But as compositions I’m proud of it, I’m pleased with it, and I don’t want to tinker with something that’s worked.”

I can’t resist asking Jeff Wayne about something that intrigues me about this album: In the early to mid-‘70s, it had become common for ‘progressive rock’ bands to release bloated concept albums, often double or triple sets with sci-fi artwork, side-long songs, and overzealously virtuosic playing. But by 1978, when Jeff Wayne’s War Of The Worlds was released, England (and most of the rest of the Western world) was in the grip of the punk rock ‘revolution’. Anything remotely smacking of gigantic concepts with buzzing synthesizers and overloaded arrangements was badgered relentlessly by the new order, and considered ‘dinosaur rock’. These days, it’s commonly accepted by music historians that punk killed off the dinosaurs… and yet, War Of The Worlds was one of the biggest sellers of 1978.

“I think you’re absolutely right,” says Wayne, warming to the subject. “It came out right at the height of the punk revolution. I think the dance beat of the day was disco, and so much of the music of the day was of the disco era, and here was my music that was coming out in that period of time. But it was music, it came honestly out of me, and I think there was a lot of passion to it, set against a classic story. I think that resonated, and I think there are many things creatively in life in all media that go against the tide. And maybe because of that, to start with, if it has an audience, the general public I don’t think really care that you’re not following a formula of the day.”

Wayne tells me that respected UK music magazine Mojo asked the same question, and “the art department then called me and said ‘Would you mind if we took your art work and had all the top punk artists of the day running away from the martian fighting machine being zapped by a heat ray?’ They thought I was going to say no, but I loved the idea, because it just said it in one image. The original musicians on the recording of War Of The Worlds remembered that we gave each other punk names on the session, because we were all mates, the basic band, and it was all done live, so yeah, you’ve actually hit on it!”

“There was a lot of passion set against a classic story… there are many things creatively in life in all media that go against the tide”

And he tells me how a Melody Maker editor wrote a positive riposte to some punk criticisms at the time of the album’s original launch, stating that ‘this could see Jeff Wayne out for the rest of his life in one form or another’.” Which could just be the most switched-on comment in this story, as Wayne has never achieved anything like the same success again (anyone remember the follow-up, Sparticus?)…yet his musical adaptation of War Of The Worlds could easily see him through to a comfortable retirement.

There are many aspects of WOTW that make it unique – from the richly buzzing and careening synthesizers to the cool guitar work to the dramatic orchestrations. But what’s really weird is the disco beats on some tracks, which one would thought would have been anathema to the progressive rock crowd of the time.

“The opening theme, The Eve Of The War, which is the main piece with a disco beat, was composed with an ear toward the dance floor,” says Wayne. “Fortunately it succeeded: it was number one in a lot of countries, and out of the over 300 remixes that we’ve had through the years in the club world, every genre of the club world from disco to today, it’s the one that’s been done the most. But when you get into a lot of the other compositions of the 96 minutes, you’ll hear a lot of other things that are unrelated to disco, that have the prog rock if you want to call it that, and the guitar work of the day. And if you look at the musicians that I worked with, they had resumes that some musicians would kill for, bands and artists that were considered the cool hip artists of the day.”

“If you look at the musicians that I worked with, they had resumes that some musicians would kill for.”

For a start, there’s guest vocals from David Essex (Wayne was the production genius behind Essex’s big glam-era hit, ‘Rock On’), Julie Covington, the Moody Blues’ Justin Hayward, Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott, and expat New Zealander Chris Thompson. Then comes the roll-call of sterling musos of the era, from guitarist Chris Spedding to bass guitarist Herbie Flowers, who was the genius behind the walking bass-line of Lou Reed’s Walk On The Wild Side.

One of the key sounds on WOTW, however, is the synths, which provide a texture to the recording that couldn’t be replicated in this digital age.

“When synthesizers became popular, I was one of the first people in England to start using them,” says Wayne. “I used to programme them myself and play them. But by the time I got to War Of The Worlds, they had moved on in a range of ways, and I worked with Ken Freeman, or ‘Prof’ as we dubbed him because he was such a genius with synths and electronics in general. Synthesisers represented sounds that were almost only limited to your imagination, because they were actually custom made. The thing about synths in those days was that they were all monophonic, so if you wanted a four note chord you had to record it four times. They were also complex in their construction and they didn’t stay in tune, and you couldn’t store them in memory, so they made custom made sounds that were very fat.”

“Synthesisers represented sounds that were almost only limited to your imagination.”

Jeff Wayne, who has made a very nice living for many years running his studio and accepting a variety of commissions for everything from contributions to rock operas (The Who) to classical pieces for the London Symphony Orchestra, thrives on diversity, and goes his own way: the man doesn’t even have an agent or a manager. His current musical tastes encompass the latest hip-hop and r’n’b (passions of his 20-year-old son, who happens to be a DJ), but he’ll be working on War Of The Worlds-related projects for quite some time to come.

“I’m going to be conducting some concert versions of War Of The Worlds starting from February, and I’ve got a large scale theatrical tour of it, where our paintings all come to life. And then our CGI music film is in production. It’s a prequel set on Mars, and it explains why the Martians have to leave, because ecologically they destroyed their own planet. So there’s a lot of life in the old Martian yet.”