GARY STEEL is celebrating 40 years of writing about music. In a life crammed with interviews, there are bound to have been a few that didn’t quite go as planned.

I’ve been really lucky. Most of the musicians I’ve interviewed over the past 40 years have been reasonably amenable. Some have been deadly dull, while others had difficulty articulating themselves. I’ve had a pretty good batting average and some of my favourite artists have also turned out to be lucid thinkers who were generous with their time and thoughts.

It’s inevitable, I guess, that along with the great and the good, there would be a few clunkers. I remember a phone interview with Henry Rollins that was so unhelpful and monotone that I was almost comatose by the end. But the bad ones I remember were really just weird. Mike Nesmith (of Monkees fame) didn’t make a lot of sense at the time, and despite efforts to disentangle logic from the interview transcript, I can’t help but wonder if the guy was off his face. Then there was over-friendly interview with Australian diva Kate Ceberano where she tried to woo me into Scientology by inviting me over to stay with her people.

There’s only really one sour interview memory: Bob Geldof. I’d only become the music writer for Wellington newspaper The Evening Post less than a year before, and I was as shy and naïve as they come. At the time I was flatting in a mouldering two-story house above Boulcott St almost directly behind the publication’s offices in Willis St. The sons of the Watties dynasty reputedly lived above us so I would punish them with Pil’s The Metal Box as loud as my Pioneer receiver and ESS speakers would go. The house was almost completely shaded by large trees and The Terrace above, and there was a gaping hole in the kitchen floor that let all kinds of vermin into the house, including hundreds of slaters that somehow found their way to drowning in a rice risotto I’d cooked up. Yes, I did eat some before I realised the “funny looking rice” was actually drowned slaters.

Anyway, the way I recall it Geldof called me an idiot. That’s not in the story, so maybe I’ve just concocted that over time based on his hostile behaviour that day.

Here’s a piece about the encounter that I wrote for Wellington City magazine in the mid-1980s:

An indignant Bob Geldof squares off against his chosen opponent and mutters something about stupid questions.

The unfriendly Irishman had already assailed a beleaguered and heretofore unsuspecting journalist with a stream of invective, which barely conceals outright contempt.

So the man doesn’t like press conferences, doesn’t like interviews, doesn’t like the process. But more to the point, he doesn’t like ME.

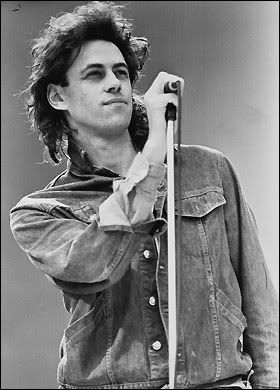

The year is 1980, and Bob Geldof, as leader of a nominally punk rock Irish group called The Boomtown Rats, must feel a responsibility to project himself with some degree of arrogance and animosity. But what, exactly, had I done wrong? This I wondered as he directed his relentless gaze in my direction, and prompted the next ‘stupid’, quick-fire question.

The day had begun with nary a hint of an encounter such as this. A lunchtime phone-call had confirmed the ‘press conference’ with the Boomtown Rats, scheduled for mid-afternoon at the James Cook. Then, disaster struck. My only acceptable, clean pair of trousers were discovered – with horror – still dripping on the line. With 10 minutes up my sleeve, I frantically attempted to iron out the moisture, and ended up despondently dragging the damp denim over my quaking loins.

Breathless, I made my grand entrance. The punk group did not appear to be here. Spotting an acquaintance, I sought refuge in pathetic banter. I hiply asserted that this Geldof fellow was widely regarded as a prat. Then the promoter appeared, and said, “Oh, Gary, Bob is just behind you and waiting…”

Sure enough, within hearing distance sat the deity. “Bob, this is Gary from The Evening Post”.

“You wrote that shitty piece about that idiot Gary Numan and his Mum”. I fervently denied having committed the offence, but my luck had run out.

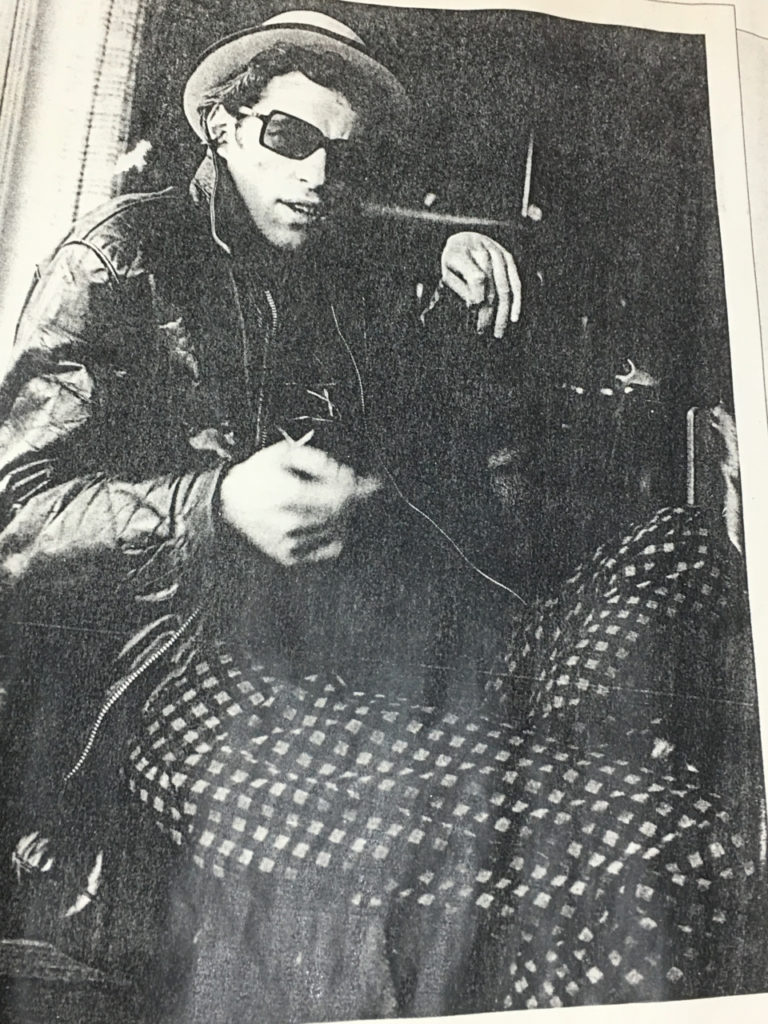

The punk rock star’s crumpled leather jacket rubbed up the lush leather chair the wrong way. Greasy locks got covered by a silly hat for hasty photographs. Likwise, shades were donned for the experience.

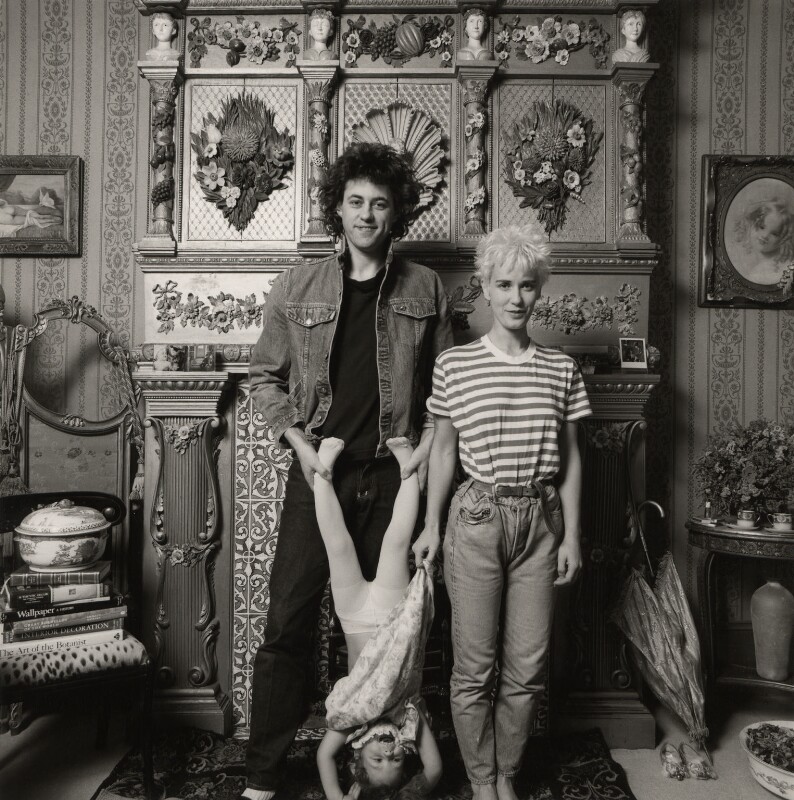

There is nothing to suggest that this is the Saint who will one day be revered the world over for his generous efforts to assist the plight of the world’s hungry; the angel who thought up the Live Aid scheme for famine relief in Ethiopia, and who wound up pictured in the world’s newspapers with his idol Mother Theresa, was little in evidence this day in 1980.

Already, his group The Boomtown Rats were in decline. Still able to muster the odd radio hit (eg, ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’) the band were already sounding tired and trad amongst the post-punk innovation predominant at the time. Likewise, ex-journalist Geldof was already in war with the English Press.

“When we liked them, they hated us”, he spat. “Now the feeling’s mutual”.

I asked him why the Press hated his group. He looked me straight in the eye and stated: “Impotent people scream the most fully”. I could have screamed.

In the light of Geldof’s recent overblown autobiography, his next comment was especially ironic. He said that much of his anger for the Press stemmed from their portrayal of his love life. It’s private, and he wants it kept that way.

“It’s completely irrelevant who Joni Mitchell fucked last week in Greece.”

Funnily, a quick glance at Geldof’s torrid tome will give an exclusive insight not only into the man’s loves, but also when, where and how many times. Even his masturbation habits don’t escape detailed examination. Check it out.

The Boomtown Rats proved that night they were without a doubt just another rock and roll band. Geldof insisted that day that what the Rats were doing was ‘relevant’ and that old-guard groups like The Rolling Stones were not, though he did admit that, “The essential R&B style of rock culture remains the same.”

The difference, he said, is that the Rats had absorbed musical influences from West India and other climes.

I asked him what he would do if he found he had nothing more to say. “I hope we have the courage to get out, or alternatively get kicked out. I would like to be around in 20 years putting out good songs.”

Why did Geldof and the Rats come to New Zealand, then? Will they make money here, or will it spur record sales? “We’ll lose $8,000 in New Zealand. If we had a platinum album in New Zealand we’d make, I think, $500.” Question answered.

A, I thought, he’s starting to open up. He’s beginning to answer in more than one-sentence, monosyllabic quick-fire retorts. We’re getting there and… he suddenly grabs the promoter and announces that he’s finished the interview. It’s over. Phew.

No goodbyes or thankyous.

What a generous man.

Yay punk rock.