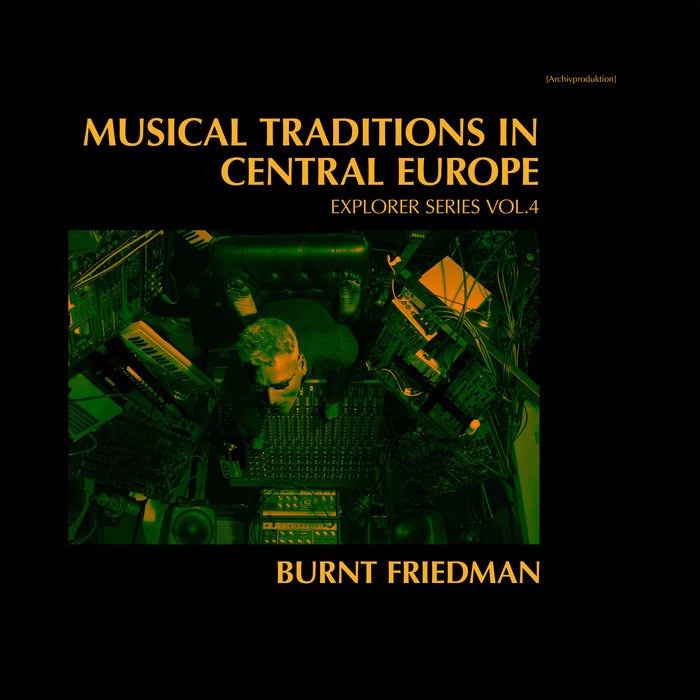

Burnt Friedman – Musical Traditions In Central Europe: Explorer Series Volume 4 (Nonplace) REVIEW

Summary

Burnt Friedman – Musical Traditions In Central Europe: Explorer Series Volume 4 (Nonplace) REVIEW

GARY STEEL renews his acquaintance with the music world of Burnt Friedman and finds it to be as exquisitely detailed as ever.

Auditioned on TIDAL HiFi

Between 1996 and 2004, German musician Burnt Friedman brought his Nonplace Urban Field project to New Zealand on multiple occasions, and his performances here were a delight for those whose expectations of a club environment were something more than a four-on-the-floor experience. As proprietor of a niche record store with irregular live performances, I was lucky enough to discover and grow to love Burnt’s music and then meet and befriend the man himself, who proved to be every bit the deeply thoughtful, creative individual I had imagined him to be… and one who was determined to go his own way.

Burnt was briefly associated with the kind of dub-influenced minimal techno that was very hip in the late ‘90s, but by the time audiences had caught up with that phase of his artistic development he’d already moved on in his restless musical exploration. By the time of his last New Zealand date in December 2004, he was knee-deep in collaborating with former Can drummer Jaki Liebezeit on a series of extraordinary albums named Secret Rhythms, but Jaki was flying phobic and Burnt essentially DJ’d some of their work to an audience that didn’t quite get it. While the music was based around percussion of various kinds, this wasn’t dance music and much of its charm was in the infinitely subtle textural and rhythmic variations.

While Burnt hasn’t been back to NZ since then, he’s kept refining his music on projects with Leibezeit (who sadly died in 2017), Uwe Schmidt (otherwise known as Senor Coconut or Atom TM but who collaborated with Friedman as Flanger) David Sylvian (in the Nine Horses project) and a range of global (and especially, African) others. Meanwhile, his Nonplace album has remained active with his own releases, on which he often works with expat New Zealand saxophonist Hayden Chisholm.

While I understand the opinion of some that his best work was on his 1996 mini-album Raum Für Notizen with its smart take on dubbed-up drum and bass or the knowing virtuosity of 1999 album Plays Love Songs, his 21st century output is just as good. The difference is that his earlier work was superficially more eclectic, while latterly he’s found a template to work within and continue to refine, and so even his latest, Musical Traditions In Central Europe, bears the traces of those Secret Rhythms albums and concentrates on the rhythms while any melodies are stripped bare.

Despite the title, which appears to be a pisstake of those dryly presented early ethnographic, pre-‘world music’ albums, his latest continues Friedman’s quest to present a music that effectively says: “Hey guys, there’s a different way to do music! How about starting out with cool percussion sounds, fucked up rhythms that might kill you if you try dancing to them, and then layering other textures on top, like smoky sax lines or indeterminate electronics that bless it a real mood?”

The last track, ‘Sky Speech’, is like that. It’s a really lonely-sounding piece that kicks around on a low-down groove while Chisholm’s sax is reproduced in close-up splendour. The first track on the other hand, ‘Supreme Self’, is an almost Can-type groove (or should I write ‘microgroove’?) with unexpected tonal irruptions via synth splurges and metallic clanging sounds.

Friedman’s recordings are always meticulously engineered and the bass on ‘Moslemschleier’ (a tribute to Bryn Jones of Muslimgauze) is low and cavernous, and while the beat is snappy there’s a general feeling of creeping entropy with its synths buzzing like electronic cicadas and just a hint of gauzy horns.

The ‘imaginary soundtrack’ angle might have been played to death years ago, but many of these would make superb haunted film soundtrack material. ‘Schwebende Himmelsbrücke’ is a case in point, with the odd metre of its rhythms (oddness echoed at that) and then a carefully painted topping that’s trippy even without drugs. (I must also note at this point that Friedman puts great care into the stereo separation).

There’s only one vocal (and thanks for that) by Brazilian singer Lucas Santtana on ‘A Cidade Que Não Morreu’, and that track – with its Portuguese lyric about Berlin – develops a hint of Latin to its sound.

I guess people like explicit emotions from their music and Burnt Friedman never provides that easy option. Every element of his music is discrete and on some level hard to fathom because it never quite reveals itself emotionally. I take that as a positive, because emotions don’t always have to be heart on sleeve but can represent the entire complexity of our human makeup, including the part of us that refuses the big reveal.

Probably my only disappointment with Musical Traditions In Central Europe is that most of the pieces are quite short, and I think they’d become even more resonant over a longer duration. Of course, I can press ‘play’ again, but I’m lazy.