It’s great that classic albums are being celebrated, but is it really necessary to trample all over the facts to prove a point?

It’s inevitable living down here in New Zealand that we hear about things a bit late, even in this gloriously instant age. I woke up this morning to learn that yesterday, two of my favourite albums turned 50 years old, and several online publications celebrated the event with pieces acclaiming them as the unique masterpieces and colossal musical events that they are.

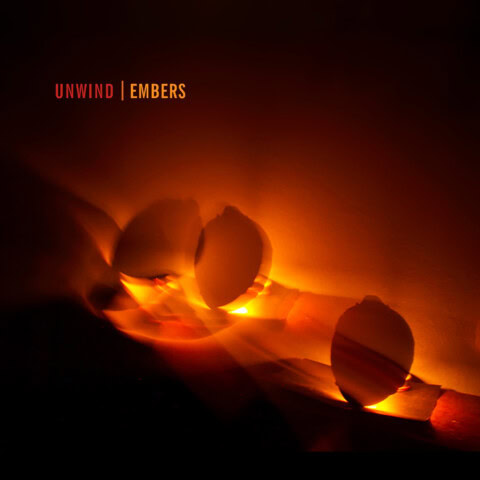

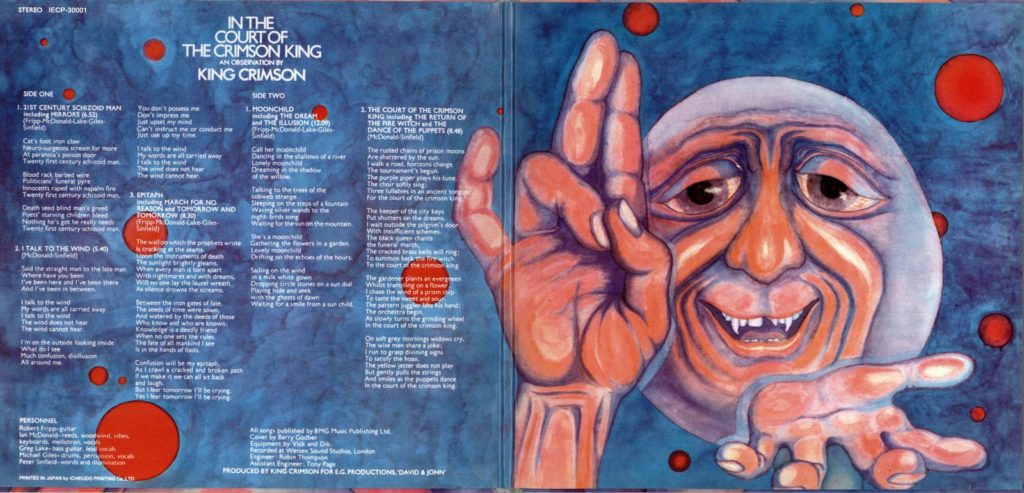

The album receiving the most attention was King Crimson’s legendary debut, In The Court Of The Crimson King, which was released on October 10, 1969. Also released the same day was Frank Zappa’s epochal Hot Rats, but despite the announcement of a forthcoming six-album box set called The Hot Rats Sessions, it received less press coverage.

After decades of derision largely caused by inflammatory and wrong-headed music press coverage sparked by the punk rock and post-punk revolution in the late ‘70s, progressive rock has been undergoing something of a rehabilitation of late, and it seems those who came of age in the ‘90s or ‘00s don’t care about those old ideological spats, and can appreciate the music for what it is.

I love it that online publications think it worth writing about an important album like In The Court Of The Crimson King, but most of them read as though they’re written by unpaid work experience novices who are doing it simply to generate alt-clicks.

Take the piece by Happy Mag, for instance. The “Australian based online music and youth culture magazine” ran a story called ‘Why It Mattered: King Crimson’s In The Court Of The Crimson King.’ The story made the usual points about how influential this album was but was littered with typographical errors, and more importantly, factual inaccuracies.

It’s worth picking apart these inaccuracies to get to a more reasoned picture of this album.

“The tortured lyrics of Greg Lake at odds with the world, are in stark contrast to the free-loving optimism of their contemporary hippie ideologies and thus King Crimson railed against the norms of the time.”

It’s certainly true that the album introduced what we might call “the apocalyptic genre” to rock, and that it went against the prevailing trends in that sense, but there were plenty of rock albums in ’69 that weren’t spouting hippie sentiment. For instance, what about the MC5 or The Stooges? The Velvet Underground could be called anti-hippies, and Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention were openly critical of flower power and everything that came with it on their 1967 (released in ’68) slice of genius, We’re Only In It For The Money.

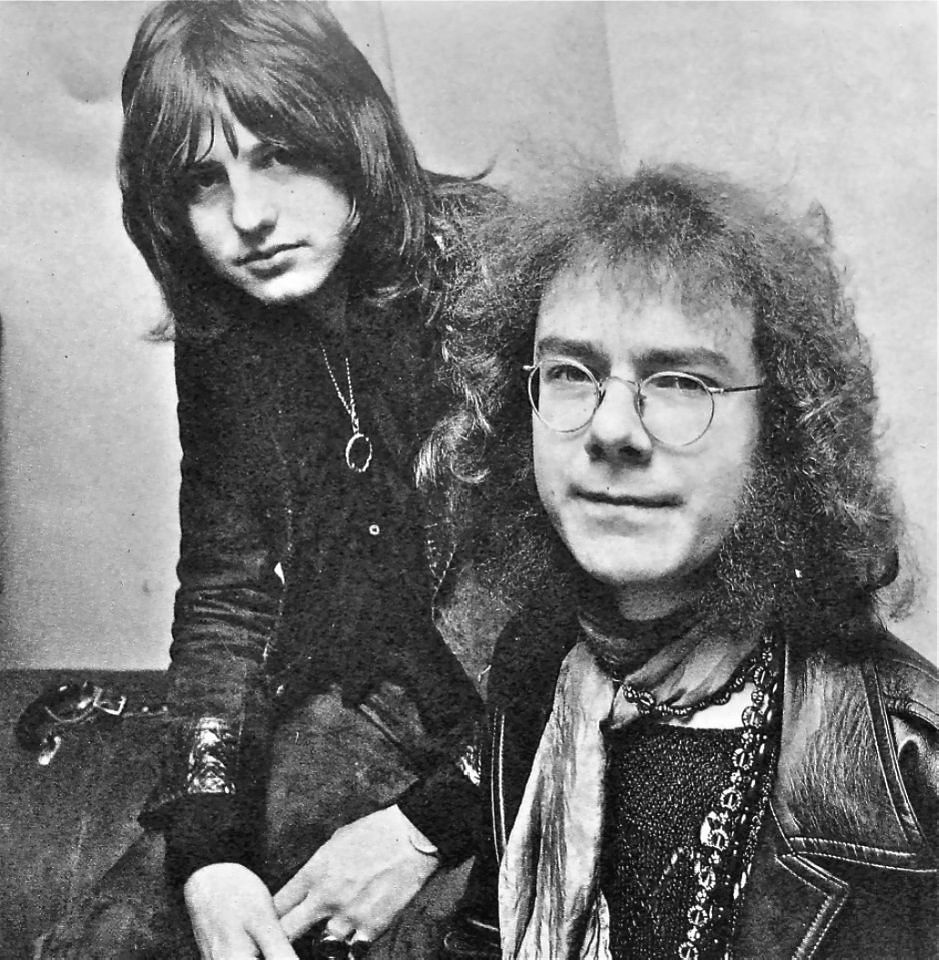

And Greg Lake’s supposed lyrics were actually penned by Pete Sinfield, a poet who went on to work with Lake in Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

“While almost all rock in the ’60s was concerned only with blues, King Crimson dared to blend it with elements of jazz, classical and symphonic music, fusing deeply emotional lyrics with hard rock.”

This is so wrong as to be laughable. Where did the writer, Luke Saunders, get this astounding piece of information? While blues was an important component of much mid-to-late ‘60s rock, many bands had long eschewed overt blues influences by the ’69. Frank Zappa had been playing around with experimental music and classical influences since ’66, and many (mostly English) groups prior to the formation of King Crimson had side-lined blues to work with said jazz and European classical influences. And what about The Beatles and The Kinks, whose work by ’67 was about as blues-influenced as George Formby.

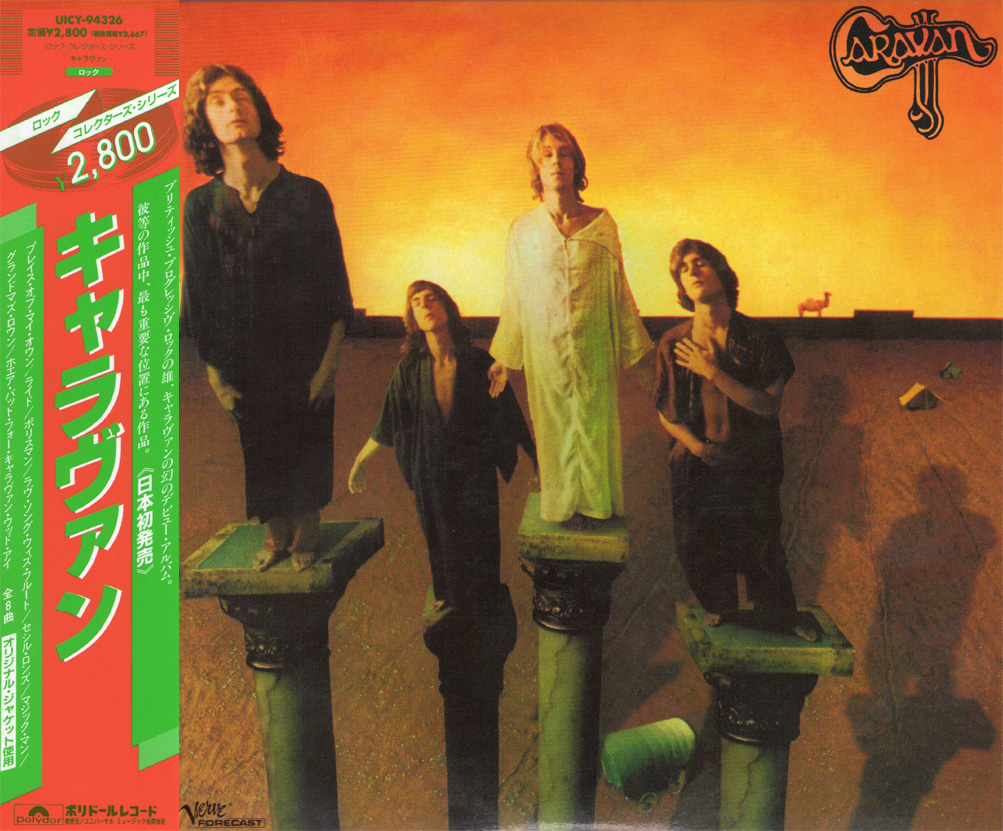

Saunders is right about one thing: that In The Court Of The Crimson King “remains a high-mark for rock music and a surreal work of power and originality”, although even here it needs pointing out that this supposed originality was really a composite gathering together of influences from other proto-progressive bands of the era. While it’s true that ITCOTCK is a landmark of progressive rock, it’s certainly not the first progressive rock album, and it’s just wrong to suggest that there isn’t a substantial body of work that preceded it by the likes of Procol Harum, The Moody Blues, The Nice, Family, Caravan, Soft Machine and several others.

It’s also true that the way Ian McDonald used the Mellotron on ITCOTCK was new, but to claim that he “challenged the rock music of the ’60s by using a Mellotron, which is in many ways a precursor to modern synths” is just silly. For starters, synthesisers were already a thing in ’69 and had been used on several rock records, most notably The Beatles’ Abbey Road. The Mellotron wasn’t a precursor to the synthesiser, but a weird attempt to create an “orchestral” instrument by using taped string sounds. Again, this instrument had been used extensively by The Beatles (‘Strawberry Fields Forever’) and The Moody Blues. What King Crimson did with The Mellotron was the point, and we’ll get to that in a minute.

The word “surreal” is used twice in Saunders’ piece, and it feels like he’s just grabbed a word that appealed to him. It’s a “surreal work of power…” and later, he refers to “the powerful, surrealist imagery”. But if anything, the album’s apocalyptic imagery is super-realist. The hippies were big on everything surreal, hence albums like Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow. Tripping with LSD was both surreal and super-real, but In The Court Of The Crimson King was the opposite to all of that. There was nothing trippy about it apart from the transformative ability of the music itself.

“The shortest song on In The Court Of The Crimson King stands at 6 minutes. The longest is double that,” claims the story. “In 1969 this was unheard of in a rock setting, especially with the endless twists, turns and breakdowns that carve out their elliptical melodic routes. This is most evident in Moonchild as the song crumbles and divulges into a highly experimental, jazzy conversation between guitar and drums.”

It would have taken Saunders less than a minute of casual Googling to establish the lie to his own lazy conclusion. By 1966, for instance, Frank Zappa was already releasing albums with songs that lasted a whole side of vinyl and even blues fusion groups like the Paul Butterfield Blues Band were releasing epic drone-raga experiments. The Nice had released the side-long Ars Longa Vita Brevis suite the year before, and even The Beatles had included all eight minutes and 22 seconds of the bizarre ‘Revolution 9’ on their ‘White Album’ in ’68. There are loads of other examples.

“It’s these moments of sheer improvisation that made King Crimson visionaries of the time and lend the album it’s [sic] renowned legacy. ‘21st Century Shizoid [sic] Man’ is often considered the first heavy metal song, whereas the album opened the door for prog-rock, which is a reigning genre even, if not especially, today.”

But the above has to be the most confounding paragraph in Saunders’ piece. I could argue with his contention that ‘Moonchild’ is a ‘moment of sheer improvisation that made King Crimson visionaries’ (to me, it’s a dull, fumbled, rambling exercise in faux-improvisation that doesn’t get close to the improvisations of the ’72-’74 version of the group). But that would be simply my opinion. But what does the last sentence even mean?

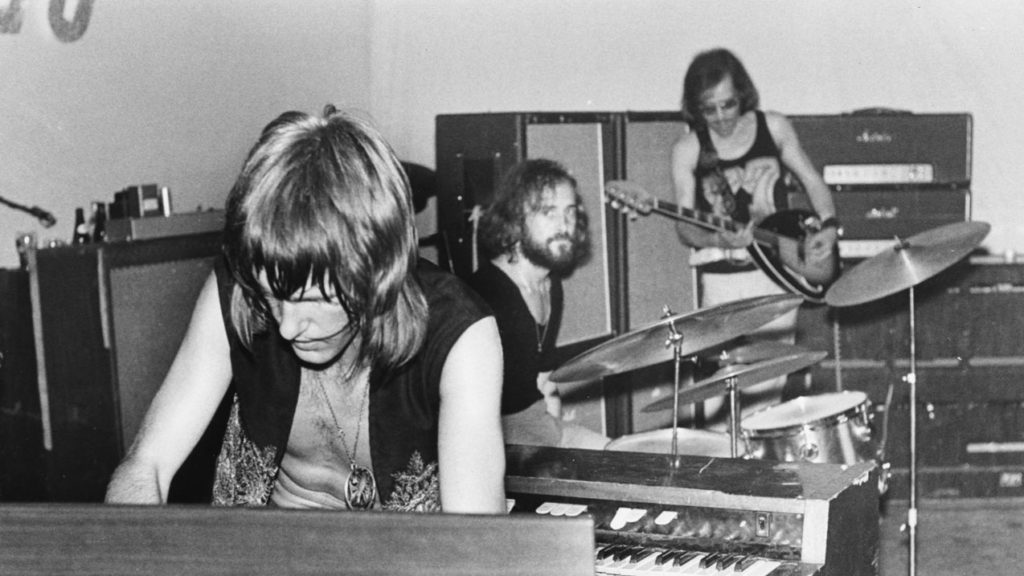

Yes, In The Court Of The Crimson King is an astonishing album, even 50 years later. But that’s because (apart from ‘Moonchild’) of factors Saunders barely considered. Yes, the apocalyptic imagery was important, together with the complexity of the writing and instrumentation, but it was also one of the best-sounding albums of the era. Back then, studios were still struggling to capture the sound of the progressive rock bands. Keith Emerson’s brilliant band The Nice is a perfect example. While their albums were full of prog-rock experimentation and brilliance, they weren’t captured particularly well.

I’ll never forget the first time I put the needle down on ITCOTCK, and the way it hit me sonically on every level, even though I was listening to it on a crappy low-wattage stereo. It was partly the way the drums were recorded, but also the way (for the first time) that loud, electric rock instrumentation was blended with acoustic sounds like Fripp’s gently picked guitar on the title track and ‘Epitaph’.

This was no small matter, and it had never been effectively achieved before – to my knowledge, at least. This successful blending of electric and acoustic is one of the hallmarks of some of the greatest progressive rock, and recording studios seemed to have figured out how to achieve it for the first time precisely at this moment in time.

Another major triumph of ITCOTCK, which is related to the above point, is the sheer dynamic of the recording. On ‘Epitaph’, the way The Mellotron surges, and gets thunderously loud, is still something that can put shivers down my spine. King Crimson became master manipulators of The Mellotron, and on recordings of live performances you can hear how they abuse the instrument almost to breaking point.

Thank goodness that the crappy early CD issues of the album have been superseded by reissues that sound as close as possible to the original album when the masters were really fresh. They’ve now been able to get at the original multi-tracks and Steven Wilson has even worked his remixing magic on the classic. I’m not always a fan of his remix re-interpretations (I don’t think he got the ELP albums quite right, for instance) but ITCOTCK sounds amazing on CD and hi-res streaming services like TIDAL.

The opening track, ‘21st Century Schizoid Man’, deserves a very long article (or even a book) of its own, because it’s a master-class in how to construct a very heavy sound with a great deal of discipline and inventiveness. I’ve heard people who should know better critique this piece as ‘prog-indulgence’, when it’s actually quite the opposite. Every single second of this 7:20 triumph justifies its existence and there’s literally no room for musical flaccidity in its very tight structure.

Happy Mag’s piece on In The Court Of The Crimson King, while laudable, is sadly the result of a world in which experts and those with something illuminating to say about great works of music are ignored for what appears to be cheap labour.

Oh, and one more thing: King Crimson, despite all the current propaganda, isn’t the only progressive rock group worth hearing. Other major prog groups like ELP, Yes, Genesis, Gentle Giant and many others (some of the best of them out of Europe) are deserving of the same exalted altar.

[But what of Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats? Witchdoctor will review the 6-CD reissue when it arrives in December.]