GARY STEEL grew up in the punk era when everyone wanted to die but few did, and wants to know why suicide is suddenly at epidemic proportions amongst NZ youth.

The badge read: ‘You’re going to die’. I made it myself, and was rather proud of it. Thirty-seven years later, I’m not sure why. It was the post-punk era, and everyone wore badges, but most of them advertised our favourite bands. In a trinkets box somewhere I still have badges for The Cure, Wellington band The Ambitious Vegetables, and a bunch of other forgotten wannabes.

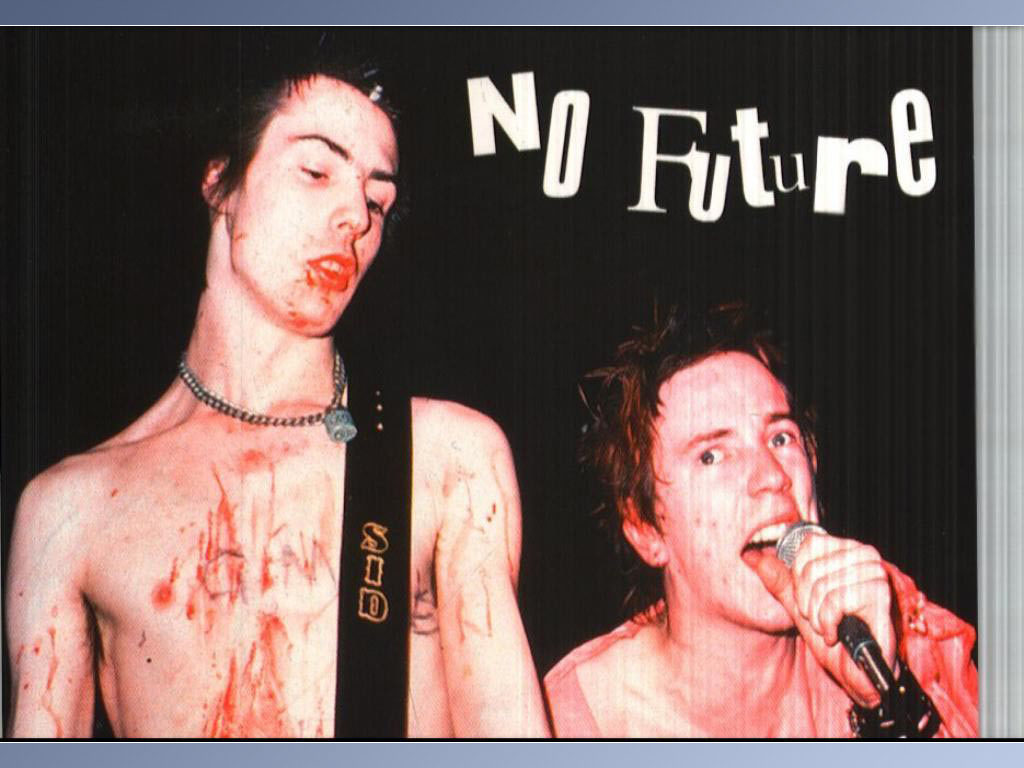

Punk was soaked in the idea of an early death. A pre-Banshees Siouxsie Sioux had promised to kill herself when she turned 20, and the dystopian aesthetic of English punk painted a dire picture of a world with, as Johnny Rotten sang, ‘No Future’.

Young death seemed to be everywhere in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, and unfortunate Sex Pistols icon Sid Vicious kicked off a particularly morbid obsession with self-destruction when he kicked the bucket on February 2, 1979, aged just 21, flying off his mortal coil on a heroin dose administered by his own mother.

Vicious represented an idiotic “oi” aspect of punk that inspired New Zealand’s so-called ‘boot boys’, a sub-sect whose modus operandi was all about violence, partying, sex, more violence, and getting totally ripped on whatever was available. The best thing about boot-boy culture was that it was guaranteed to snuff itself out, and many of them died, or ended up in prison.

But really, punk’s obsession with death was just another generation’s version of a ritual that’s been going on for at least as long as teenagers have existed, which means it goes back as far as 1953 biker film The Wild One. It didn’t matter what Johnny was rebelling against, just that young males (in particular) tend to go hog-wild at a certain age, and feeling the need for danger, cannot contain the rage implanted by their own hormonal imperatives.

Back in the 1950s, however, intentional death wasn’t on the radar. It was enough that the first clutch of baby boomers were growing up to rebel against the hard-won security their parents had established for themselves in the wake of the deprivations of World War II. Sure, they were behaving like loons, and risking fiery immolation on fast bikes and in shagging wagons, but their behaviour was more of an expression of freedom, a breaking away from their parents’ careful conservatism.

To a large degree, the flowering of the psychedelic generation a decade later was a reiteration of the same urge, but with a much greater skill set and knowledge base and belief in themselves to make a new world in their image. But instead of playing dangerous games with cars and motorbikes, freedom brought death by drugs.

I went through my difficult adolescence soaked in death; not first-hand death, but it might as well have been. I turned 11 in 1970, the year that both Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin carked it, and the following year brought the death of The Doors’ Jim Morrison. I can’t even begin to explain how much I loved the music of all three, via my older sister’s record collection, and their deaths hit me hard. Joplin’s was particularly hard to handle, because I identified with her, and I just couldn’t believe that she wouldn’t become ‘undead’ and make more great music. When I read Peggy Casserta’s outrageous Going Down With Janis book in 1973, I remember turning the page and hoping that somehow, somehow the end of the book would bring a different ending than her overdosing on heroin in a lonely motel room, and breaking her nose on the way down.

In the pre-punk rock era, though, while death was everywhere (and my growing record collection was full of dead rock stars), there was no notion of suicide. There was something to fight for: freedom. That was reason enough to live. Although punk was full of hatred and loathing, the first time I even really knew a person could kill himself was when Joy Division’s Ian Curtis was found hanging on a rope on 19 May 1980. That was when it hit me: was it even worth living? The world was just so full of pain. And we were all going to die eventually, anyway.

I was going through a personal hell at the time, having contracted an illness that left me exhausted for the best part of a year, and depressed at having to skulk back to the parents home for some rest and rehabilitation. Oh, and I didn’t have a girlfriend. Immersing myself in Joy Division’s music wasn’t exactly good for my spirits, and the more I listened, the more Ian Curtis’s death wish seemed to express itself through the lyrics and the sound.

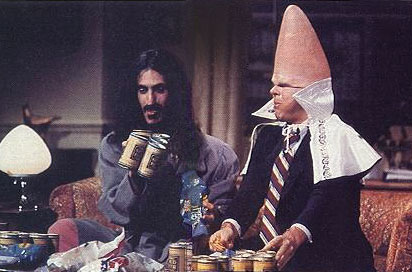

Luckily, I was also listening to a lot of Frank Zappa at the time, especially the ‘comeback’ album Sheik Yerbouti, which was full of absolutely merciless lampooning of sensitive souls. Songs like ‘Broken Hearts Are For Assholes’ were harsh, but provided a great antidote to wallowing in misery. Later, he even dared to release a song called ‘Suicide Chump’, in which the ugly, lonely protagonist is urged to ‘get it all over with then, find a bridge and take a jump’. I hate to think the stink a song like that would cause if released in 2017, but listened to in the knowledge of the Zappa ethos, it made sense. It was tough love, and it worked for me, and helped me out of my emotional nosedive.

Suicide became ‘a thing’ after Ian Curtis. It wasn’t until decades later, unfortunately, that we learned just how difficult his life had been, and how physically challenged he was with the increasing regularity of debilitating epileptic seizures. No, he wasn’t just some chump who had been dumped by his girlfriend and was feeling blue.

In the wake of Joy Division and the suicidal meanderings of their posthumous album, Closer, a whole scene of dour rock bands emerged. It was the beginning of what became known as ‘goth’, and while the more style obsessed goth bands were capable of a kind of Hammer horror glam, there was an undercurrent of self-loathing and nihilism.

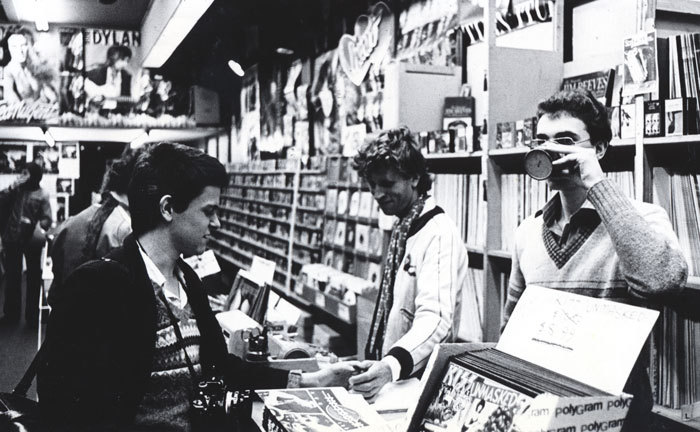

I lost my first friend to suicide in 1985, and sometimes, I still feel the shockwaves. Peter Corbishley had been ad manager for my first , self-published rock magazine, and worked for Wellington’s Colin Morris Records shop. We’d become fast friends over a shared interest in the sonic properties of contemporary rock on large stereos (often with the added input of a mild hallucinogen). He was a lovely chap, and a real taste-maker: he knew all the latest, hottest sounds and imports at a time when it was still difficult getting the most interesting records. We both loved synthesisers and weird sound effects and he’d come over to my flat beneath the Terrace where, in the early ‘80s, we’d crank up albums by Chrome and Simple Minds. He went on to become something of an entrepreneur, putting on the first successful video dance nights at local clubs and ultimately, scored a great job at RIANZ.

Unfortunately, there was a less happy parallel dimension. Peter’s Mum had died, after which he had discovered that he was adopted. To add to that, he came out as gay, but was terrified at both the social stigma and the perceived danger with the AIDS epidemic just getting underway. Then his much-loved corgi got terminally ill. He took it to the vet, where he had it put down, came home, and killed himself by carbon monoxide in his garage. He’d carefully organised everything, down to his will and funeral instructions: even the depressing songs to be played during the funeral. When his flatmate called to tell me of his death, my automatic response was “you’re joking!” – two words that Peter had used incessantly in conversation. “No, I’m not joking,” replied the flatmate.

A few months before, Peter had helped me move out of a squalid, rotting flat and driving in his car, after a conversation about how shit the latest Simple Minds album was, he started talking about suicide. It never occurred to me that it was anything other than a conversation about a subject. In the weeks after his death, that fact gnawed at me. If I’d been more perceptive, could I have done something to prevent it?

Peter was a great guy, and had a promising future. To me, it still feels as though it’s wrong that he’s not around: that somehow the fabric of time has been punctured, that the way my life played out was somehow sullied, not by the event, but by his unexpected absence. He’s still in my dreams occasionally.

What really caused it? I’ll never know, but had Peter’s background been more stable, and had he been using less marijuana, or listening to less morbid music, then perhaps he may have just found the conviction to stay with us.

I’m 58 now, so quite a few friends and acquaintances have killed themselves over the years, either through suicide or slow suicide via addiction to drugs and alcohol. One thing’s for sure: it never gets any easier to cope with, and the response is always like an emotional tumble-dryer where one minute you’re hating them for their selfishness, and the next minute you’re loving the fact that they lived at all, or feeling guilty that maybe you could have done something to prevent it.

Amongst my age group, the most common reason for unexpected suicide seems to be around the difficulties in relationships; something that I find hard to fathom, maybe because I’m just too self-composed (some would say selfish) and like my own company. I’ve asked myself from time to time under which circumstances I might consider taking my own life, and really, there’s only one: when illness becomes so bad that the quality of life is completely eroded, with no sign of improvement. I would be heartbroken if my wife left me, and deeply depressed if I lost my home, but I love life itself too much to want to escape the emotional pain wrought by its experiences. I have an auto-immune condition that flares up now and again, and will probably eventually kill me (if something else doesn’t come along to write me off first) and I can imagine ending up being so sore and frail that there’s just no fun to be had anymore. But while I can still find pleasure in proportion to the pain, ending life is untenable.

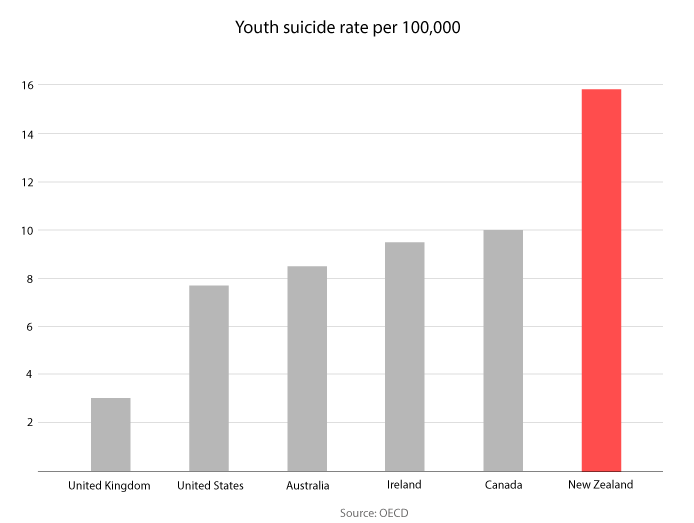

So, what of the current ‘suicide epidemic’ amongst our very young in New Zealand? What’s that all about, and what can be done about it? Beats me, but I’m glad that the ‘experts’ are no longer insisting that we don’t talk about suicide. It’s easy to understand the reasoning behind silence, because just talking about something can legitimise it and potentially cause a spike in the activity. But actually, talking about it is the only way the problem can be addressed.

Obviously, the suicidal impulse isn’t just caused by just one thing, and there’s a vast difference between someone with mental illness and someone who, for reasons of their own, just decides that they don’t want to be here anymore. Mental illness causes faulty reasoning, so that’s beyond the scope of this essay. But what about all the young people who choose suicide, but are not afflicted with mental illness?

I’d really like to see some analysis of youth suicides. Do most of them come from well-off or financially deprived families? From good schools or bad schools? Are they at-risk youths to begin with? Are the majority copycat suicides? How often do they give a reason for killing themselves? How do they usually kill themselves? What’s the ratio of successful to failed suicides? Which age do youth suicides reach their peak? Where are the majority of suicides? Rural or city?

I’d also like to know whether schools teach any life methodology – you know, philosophy or anything that gets them thinking about what life is – now that religious instruction isn’t allowed.

My generation – even though it liked the idea of dying before it got old, because the older generation were seen as the upholders of outmoded values – essentially loved life. Part of what made life have meaning was that we felt we could change the world, and find better ways of doing things. There was also a glistening, technology-led utopia just around the bend where robots did all the boring work, freeing us up to have more fun. Well, that didn’t exactly happen, but…

Perhaps they’re killing themselves for same reason that so many of them won’t vote in the elections: they’ve not been raised with the critical faculties to understand that they do have a voice and a part to play. Maybe, because they’ve been raised under the harsh, arrogant and un-empathetic governance of National, they’ve simply not been empowered to believe there’s anything of value to aspire to.

I grew up in a boring New Zealand that felt light years away from anything exciting, but in some ways, it was better than the New Zealand most young people are growing up in today. For all its flaws, there was no hole in the culture that needed filling with endless strip malls comprising of the same branded made-in-china items. Families actually meant families, with mum and dad and the kids all having regular quality time together, and eating most of their meals together. Eating well and getting outdoors wasn’t an option, and we weren’t glued to smartphones, because they didn’t exist. We knew how to enjoy spending time by ourselves. We didn’t have a lot of plastic junk, but we had imaginations. Okay, old man alert, but you get the point.

There’s a great, if somewhat morbid, song by Richard and Linda Thompson called ‘End Of The Rainbow’ (1974) in which the song’s narrator is speaking directly to a baby at its mother’s breast: “Life seems so rosy in the cradle/But I’ll be a friend I’ll tell you what’s in store/There’s nothing at the end of the rainbow/There’s nothing to grow up for anymore.”

The song outlines some of the horrid things the infant can expect to endure through a disappointing life, but in reality, it’s more of a social commentary on what’s wrong with society than it is a recommendation to suicide. After all, despite the morose nature of the song, Richard Thompson clearly thinks it’s worth living, worth singing, work spanking that plank, worth making a record.

I wonder though, if there’s a generation now who really don’t know how to value life, or have the means to assess their experience of it. With the majority of parents working long hours to maintain inflated mortgages and upwardly mobile ‘lifestyles’ that really just get them into the malls at the weekend to buy useless shit, what are these kids getting that’s of any value? No wonder that, at the first sign of disappointment with what life has to offer, they simply opt to turn off the switch.

And with a spike in suicides by the very, very young, what hope is there that they can even start to understand that suicide is forever? And there’s the thing: most of us, faced with a dark time, occasionally think ‘wouldn’t it be nice to just not be here at the moment… you know, just until the hurt goes away?’ But most of us know that’s not possible; that there’s no way of killing yourself and coming back for more when the pain has subsided. I wouldn’t mind betting that most suicides are simply about making the pain go away, and that few of them realise that by not dealing with the pain and getting through it, that there never will be something to be gained from that pain.

There’s a fantastic riffy piece by King Crimson’s Robert Fripp from the late ‘70s called ‘Exposure’, where he loops parts of a speech by G. J. Bennett, an English disciple of philosopher-guru Gurdjieff saying, “It is impossible to achieve the aim without suffering.” I wonder if any of today’s kids get told that there’s no gain without pain; and that there’s nothing quite like breaking through to the other side, not to death and oblivion, but to a place where you value every moment on earth. Because death comes quickly enough. And yeah, you’re going to die.