We all see, hear and engage with the world differently in our great sensorial mismatch, explains DR RICHARD VAREY. But how does that relate to hi-fi? Read on to find out.

After enthusing about music and hi-fi for more than four decades my interest is undiminished, so it’s intriguing to see articles and forum discussions heralding the death of hi-fi. This is both disappointing and discomforting. And did I say puzzling? I’ve been thinking about what hi-fi once was, what it became, and what it may become.

Firstly, which hi-fi is supposedly dying? Words and meanings get mixed, mulched, mashed up and matched up, and the relationships change.

Originally, stereo was the sound effect for musical instrument placement within a two or three-dimensional image created in the two channel playback of a recording, then it also referred to the home audio equipment needed for that. High-fidelity originally was the audible quality of a sound system desirable for pleasurable true music listening, then it also came to refer to the equipment.

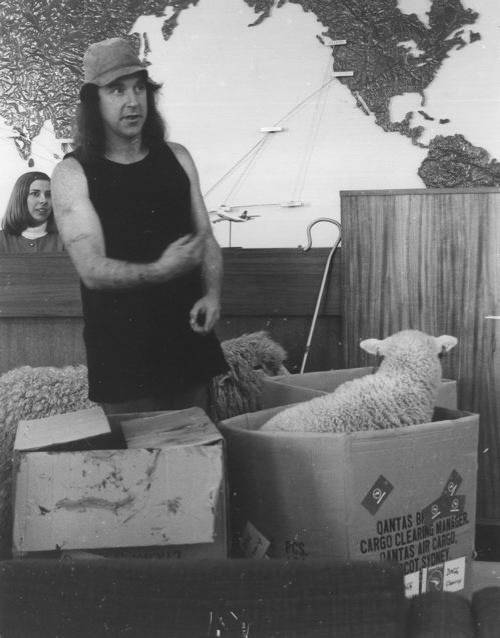

It’s as if, by knowing the equipment, the auditory experience would be apparent. Hi-fi became synonymous with shiny knobs and coloured lights, once the hallowed domain of the enthusiast knowledgeable in technical specifications and jargon. He (and hardly ever she) is the addicted technophile endlessly seeking audio equipment perfection. To everyone else, hi-fi was simply the reproduction of music for the pleasure of listening.

And therein lies a confusion and a distraction because now everything is a ‘hi-fi’ or a ‘stereo’, even when it isn’t, and lo-fi and mono products are sold under ubiquitous, generic, and therefore sometimes misleading terms. This vague blurring generalisation has devalued the original benefits and purpose, and confused any discussion of the state of interest in and commitment to playing music with high sound quality or high performance equipment.

Hi-fi isn’t dying, it’s evolving. And it’s not the narrow interest of a single amorphous homogenous collection of like-minded enthusiasts/hobbyists/yellow cardigan-wearers. People are different, and some enjoy music in a quite different way to others, and for some of them hi-fi is salient as a necessary means. Within that sub-group of the population, there are substantial differences in attitude towards what is needed for music listening.

Marketers identify five sub-groups of attitudes to technology, and I don’t mean the ‘price points’ that marketers use to tell us that we’re not spending enough on their products. They also label us as ‘consumers’ who behave differently and need to be treated with various sales appeals accordingly.

Some of us crave the new, while others are content with the familiar. The first to enthuse over and adopt a new technology are the very small minority of well-informed risk-takers (Innovators), and later the educated opinion leaders who follow positive response from the innovators (Early Adopters). The majority of users are careful to avoid risk, relying on recommendations from experienced users (Early Majority), or somewhat sceptical and only adopting products when they are commonplace (Late Majority). There are also a few who avoid change and may only adopt a new product when the original options have been withdrawn (Laggards).

Hi-fi laggards are holding onto the past with the technology they grew up with in the heyday of the then-new stereo revolution in home listening. At any time, there are people with one of such attitudes to hearing music recordings. Advertising of a new product is initially directed to innovators and early adopters, and reviewers can be found among these pioneers and champions. And perhaps these attitudes align with the commonly used labels Technophile and Audiophile, as well as the less common Musicophile (the latter is probably more common in music discussions). The technophiles are the innovators and early adopters. The audiophiles are the majority, and the musicophiles are the laggards. Now there’s a contentious generalising hypothesis!

Who says hi-fi is dying? The parties to this sub-culture are the equipment makers, the sellers, and we users. I’ve heard a dealer tell a customer that there’s no demand for separate components anymore (they had asked for separates), but tell that to the designers and producers. What we are witnessing is a shift from a mass market (was much of it really ever truly hi-fi anyway?) to hi-fi connoisseurship. We are experiencing a shift from high street retailing of products.

What we are being told daily is that it’s all about streaming and yet we also have a ‘vinyl resurgence’, apparently. I see a disaggregation. On the one hand, it’s like watching the grazing herd follow the lead beasts to a fresh patch of grass. More music is consumed as a temporary entertainment, on the move. Yet for the culture vulture who seeks deep experience, the art matters far more than the technology. Engagement attracts more than convenience. Performance more than low price. Collection curation, not instant gratification through consumption. So music listening is ever more a transitory service for the masses, and a human connection with the artist for the musicophile.

Hearing habits are changing, as is the significance of music and listening in our culture. Maybe it’s not cool anymore. For most people, it never has been. The people who think it’s dead have never had it as part of their lives anyway. The deep immersive listening experience without distracting activity appeals to only a few. The ubiquitous ‘stereo’ was never really hi-fi, just like Hoover have had far more strings to their bow than vacuum cleaners.

There’s a cultural dimension to this story. This shift in focus (a visual concept) is to be expected in cultural terms as we move from an oral (auditory) tradition to a predominantly visual future. This mega-trend was noticed and documented 50 years ago by Marshall McLuhan and others. It started hundreds of years ago with the outgrowth of writing and reading, which later fuelled science and the Industrial Revolution, leading to radical reforms of religion and government as visual literacy displaces the oral tradition. Our minds were retrained to the analytical linear reductive thinking of the visual, in place of the all-at-once always on holistic sound field of the oral. Our ears have become subordinated to our eyes.

Listening is now to be worked at as a special skill. Once radio enthralled precisely because sound was the exciter of imagination (pictures in the mind). Now we have merged the TV with the stereo and crave multi-channel home theatre with ever bigger screens. The visual immersion experience has come to dominate. Videos came to music on TV, and YouTube replaced LPs and CDs, which were discarded in favour first of DVDs and now streaming videos. Visuals with sound is the bare minimum required to grasp our attention. Continual change is craved, putting an end to albums and collections for all but the sensorially retarded. (And yes, I count myself in that category, as a 61-years-old who has listened to recorded music from his own collection since 1972. I’m a musical laggard).

We are not the same. Just as attitude to new technology differs, so too do we find differing sensoriums (the set of human senses). Some of us emphasise or favour our sight, or our hearing, or touch, or smell, or intuition. This is why we communicate differently as we engage with our world, and behave differently towards others. Sensorial mismatch partly explains introvert-extravert differences in personality, for example.

This leads to the question: How does personality influence music choice and the relative appeal of technology, sound quality, and music? I’ll be writing about this soon. Values are shifting. Fashions come and go in style waves or cycles. The appeal of convenience, cost, sound quality/fidelity, performance, brand reputation, aesthetics of design and appearance differs from person to person, and always changes.

Which hi-fi is dying? Is it the technophile’s hardware and software, or the audiophile’s beloved sound quality? Does sound quality matter because it’s about technical perfection and performance, or because it’s about audio fidelity and musical engagement? The former enhances the latter, so logically it’s about both. Hi-fi certainly isn’t terminally ill in the ears of the audiophile musicophile.

The technically inclined user stops short at the perfection of engineering. Music ‘content’ is generally little more than a means to demonstrate audio playback performance. The audiophile wants to hear what was recorded, unencumbered by distortions. The musicophile may care little for either. That is, until they hear their favourite recordings in all their glory, and then they may come to appreciate sound quality and maybe even the design and manufacturing values of the equipment. Most people care little about any of this. Most don’t need a hi-fi music player, they can stream to a phone, and have no committed interest in technology, audio fidelity, or music. They are not reading this article! And I’m not one of them.

Is hi-fi dying? For some of us it’s evolving in diversified media and formats. Others doggedly stick with their favoured way of playing recordings. Fans of Reggie Perrin will fondly recall that CJ might once have said that he “didn’t get where he was by liking CDs more than LPs” (or vice versa).

Hi-fi dead? Nah, long live hi-fi. Hi-fi is not dead. It resides healthily in the audiophile communities, not the high street. I think it’s the stereo stereotype that is fading, but for those who remain faithful, the hi-fi hype rumbles on apace.