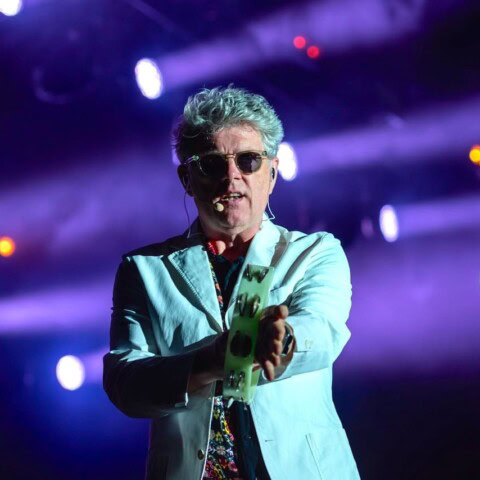

The idea? Every day in May, to mark NZ Music Month and 38 years of his own rancid opining and reportage, Gary Steel will present something from his considerable behind. Personal archive, that is. The following story appeared in Real Groove, July 1995.

GODZONE’S PROG-ZONE

GARY STEEL WANDERS THROUGH THE MURKY PAST OF KIWI ROCK’S ’70s LEAPS INTO THE COSMIC.

IN NEW ZEALAND, nothing really changes: our own rock history isn’t treated with any respect or reverence and many important groups are still waiting for a CD reissue.

In a country that doesn’t even bother to reissue the full albums by rock’n’roll icons like Hello Sailor and Th’Dudes (back to back selections on one CD, folks), it’s no wonder that our progressive rock bands have been all but forgotten.

In truth, the Kiwi prog-rock scene never proliferated, simply because the technology wasn’t readily available: very few groups had the obligatory synthesisers and (legend has it) only one Mellotron ever made it to these far-flung isles.

Which meant that the poor overworked beastie (the Mellotron, that is) had to be shared around a number of bands, central to which were Split Enz, Alistair Riddell’s Space Waltz and Ragnarok.

One of the earliest inclinations towards prog-rock was found in early Dragon. Their second album, Scented Gardens For The Blind – resplendent in the most godawful cosmic cover art ever committed to a record sleeve – had some (frankly underpowered) pseudo-prog riffery, and some woefully ill-considered mystic imagery. It was embarrassing stuff. They were to make a much better pop act.

Guitarists Harvey Mandel (Space Farm) and Eddie Hansen (Ticket) graduated to the spaced-out sounds of the Krishna-devotional Living Force, a godsend to Santana/John McLaughlin fans and a crashing bore to everyone else.

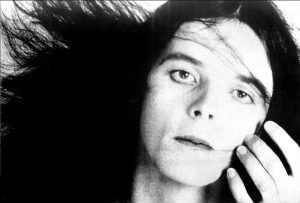

Split Enz can be heard in their most prog-rock infected phase on their first, Australian-recorded album, the legendary and still awesome Mental Notes. This was the true flourishing of Kiwi prog: classical influences, Mellotron-heavy, killer chords. It was influenced by Genesis, but the frankly psychotic presence/lyrics/singing of Phil Judd took it into another dimension.

Space Waltz (originally called The Orb!) hardly rate a mention here because, despite a slightly prog influence (they did covers by King Crimson), they were primarily influenced by the glam movement, and especially Bowie. However, they did have a synthesiser which was homebuilt by Enz electronic genius, Paul Crowther.

In 1995, Crowther is making his own Theremins for people like Chris Knox (the Theremin is the weird instrument that warbles away on the Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’ and is often associated with ’50s sci-fi movies).

Mother Goose were a novelty group from Dunedin who – when they weren’t doing songs like ‘Baked Beans’ and wearing pink tutus – had a synth-oriented sound which was far too close to Genesis to be called original. Nevertheless, they were one of the more successful Kiwi bands of the era, even taking their schtick to Australia.

BLERTA started out playing far out rock and graduated to a progressive jazz blend. They were far too eclectic to be tagged a straight prog-rock band, but some of the instrumental work-outs on their two albums This Is The Life and Wildman still stand up as special in the genre.

By the time Ragnarock and Schtung were up and running, the punk rock thing was already hitting big in England. But with the benefit of time, one can look back and appreciate the good things that were out of time in their own time.

Ragnarock were true originals. Laden with the sound of heaving Mellotrons, but pulsing with a heavy atom heart rhythm section, the early version (and their first, self-titled album) featured Lea Maalfrid, who went onto become a successful songwriter for people like Bonnie Raitt. Their lyrics were all about cosmic apparitions and Viking mythology, and were taken a step further on their second album, Nooks.

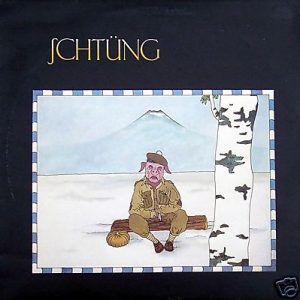

Schtung were an eccentric, inward-looking lot from Wellington, whose whimsical music was very English art school-sounding, but for all that quite unique in its unsettling tunefulness. Their one 1977 album is a forgotten classic, with its bizarre songs about talking to trees and its Monty Python sense of humour.

Personally, I’m anxiously waiting for an elaborately packaged and carefully annotated box set devoted to Kiwi prog rock. Alas, it’s but a dream. GARY STEEL

Notes: Nick Bollinger was editing Real Groove magazine in 1995 when he commissioned me to do a thematic bunch of stories on prog-rock bands for the July issue, to which I added the above piece on NZ prog. Sadly, while NZ music is now revered and AudioCulture has built up an incredible archive on its history, most of the albums mentioned in this story never did get a CD release, although a few of them have recently become available as downloads. Another possibly irrelevant footnote: I recently interviewed the business manager of my local medical centre out in Helensville, and it turns out he was one of the bass players in The Orb!