Peter Kearns introduces the newly refabricated Juju Jukebox, in which he laments the tiny percentage of good stuff on the current scene, and gives his surprise endorsement to some classic Aussie rockers.

IN THE FIRST three months of 2015 I must’ve listened to four or maybe five hundred new releases and wrote about some of them here. From that amount I found about five that I liked enough to keep, and probably less that I’d actually fork out for. That’s one fussy reviewer right there. I concluded there must be more to life than spending endless hours assessing what in 2015 amounts to 95 percent of product being mere drivel.

So, with the help of a little Witchdoctor hoodoo, the Juju Jukebox has transformed from multi-review platform into a commentary on music in general: Where is it at? Where is it going? Whatever. Throw in some song links, opinion, cultural reference, reviews, etc, and we have something a bit more flexible than it was. You’re still thinking about the 95 percent drivel, aren’t you?

Settle down. That means five percent of it is actually great! So, how do you find that five percent amongst all the clutter? Not from streaming service playlists designed to group together music of a similar ilk or tunes to accompany a sunset or a spot of spring-cleaning, that’s for sure. That just devalues music and reduces its consumption to a companion to the mundane.

But that five percent is worth fighting for. It’s recognised by quality performance of quality composition, in any genre. It’s that simple. Or it can contain either/or. A fine performance of a less than thrilling song can be a satisfying experience, as can a fabulously written song performed merely adequately. I’m more likely to go for the latter since I listen for writing first, but impressive instrumental technique on top of an uninteresting composition will rarely turn my head. And it shouldn’t turn yours. After all, who cares how good the tools and builders were if the end result is a safe, careful, perfectly executed box? As we’ve seen, that serves only to encourage the creation of further perfect safe unadventurous boxes. The architecture is where it’s at, at least for me.

That’s not to say there’s not an audience for, or even satisfaction in, pure instrumental or vocal technique. Of course there is. For example, the repertoire of smooth jazz can certainly testify to that, being as it is often populated by fabulous players of a once incredible repertoire that suddenly executed a 120- degree nosedive from 1980-something onwards, give or take. In fact, the dive was made before the term smooth jazz was even coined. Back then it was known as jazz/rock or fusion. Ironically, what they now call smooth jazz is the remaining husk of jazz/rock – that’s to say the high level of performance remains (usually), but most of the harmonic interest has been shaven off. Smooth jazz, like many genres now, is a reduction, a homogenised vehicle for mass delivery, a safe bland mood to hold your hand through a haircut. And it’s damn good at it too.

But I digress. In my 500-album journey I was also given sufficient evidence of the current lack of inspired lyric writing. There’s barely anything adventurous or incendiary going on, just this endless 95 percent meaningless mediocrity. I was going to give my usual line about there being too many songs about love and dancing, but of course subject matter is not up for judgment. There are many great lyrics on those subjects (dancing?). It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it that counts. I’m sorry, there’s no new Bob Dylan on the horizon, regardless of what they say about Australia’s Courtney Barnett. Although her use of language is superior to much of the new school. She’s one to watch.

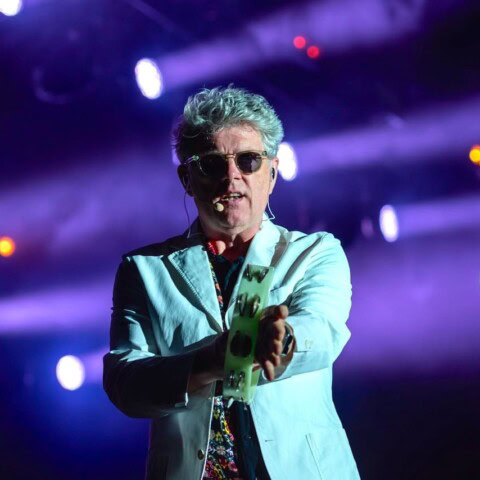

And that reminds me, to close, yesterday in the car, up popped a 1983 song by Courtney’s fellow countrymen, Little River Band – those fine purveyors of perfectly-crafted pop masterpieces. Perhaps not as widely known as their many chart-toppers, ‘The Net’ was for them a rare moment of political and sociological distress and prophecy that has most definitely come to pass. All fire has indeed been suppressed. Someone or something back then popped this gem into the lap of not the Bonos or the Stings, but LRB. Who in popular song today is telling us what’s coming in quite the same way, or at all, while playing and arranging so succinctly, and singing like that? Not many. If any. PETER KEARNS