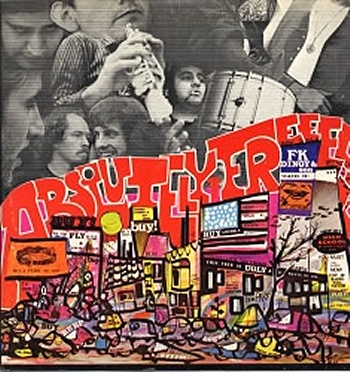

With Universal about to issue remastered versions of Frank Zappa’s enormous catalogue, Gary Steel takes up the challenge of reviewing one of FZ’s genius album creations every day. Today’s selection: Absolutely Free.

I WAS JUST 14 when I first heard Absolutely Free, and it blew my adolescent mind. Some would contend that this fact prevents me from seeing this work in its true light, and critiquing it with any degree of impartiality. To that, I politely request them to blow it out their fat ass: many albums came and went during my early infatuation with rock music, but the ones that still resonate today don’t do so for merely nostalgic reasons, because I’m just not a nostalgic kind of guy. In fact, I find it impossible not to assess, and reassess, the music in my life, and many of my favourites at the age of 14 are very low in my current estimation, or entirely forgotten.

But it’s not about me, it’s about Absolutely Free, one of the most astonishing records of the ‘60s, and well deserving a place in the top 25 per cent of the Zappa canon.

While the first Mothers album, Freak Out! was allocated an immense budget for an unknown act, its follow-up, Absolutely Free, cost reportedly just $11K, and was cut in a rushed 25 hours of studio time in the latter half of 1966. The result was a brash, challenging but always exciting record that could lay claims to several firsts: It was literally the first ‘rock opera’, and even had its own libretto (the lyrics are reproduced in the liners, the libretto is not), and the tracks literally segued from one to the next. This fact may sound unremarkable today, but was revolutionary at the time, and one direct result was Paul McCartney – who held Zappa on a pedestal – carrying through these techniques into The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band later in the year.

Fans of Zappa’s sophisticated later instrumentalism often find Absolutely Free just too anarchic and freaky and noisy and undisciplined, and some listeners never make it past the overtly silly voicings on the first side and its extended songs about the vegetable kingdom. That’s their loss, because, despite its almost punk-like brashness, with repeated exposure the madness soon comes into focus; and then there’s the second side, which delivers a one-two punch of sustained brilliance that anticipates both the alt-pop genius of We’re Only In It For The Money less than a year later, and the extended experiments of Uncle Meat soon after that.

The two sides of the vinyl of Absolutely Free are presented as two suites of unbroken music, an oratorio that takes us through the miscellaneous ills of (then) contemporary American society as Zappa saw it, from corrupt politicians to alcoholic parents who don’t understand their out-of-control kids, who themselves get blasted for superficial lifestyles and moronic behaviour. The Los Angeles that’s on display here is riven with the sometimes violent contradictions that were obvious in ’66, both social and political, except that Zappa’s take on it was self-analytical, and refused to just fall in line behind the hippy movement. Courageously, it looked at what was behind the sickness in society, and invited people to examine their own convictions.

Right from the opening dialogue – where the president’s wife brings up her chicken soup – there’s a sense that anything could happen in the madness of the ensuing 40 minutes. ‘Plastic People’, like many of these songs, works on multiple levels, both musically and lyrically, where sometimes several stories are being told or played out at once, and there’s such a gaggle of vocalists that another of Zappa’s firsts presents itself: this was a kind of rock theatre, years before the conceits of The Who’s Tommy. In ‘Plastic People’, on one hand “there’s this guy from the CIA creeping around Laurel Canyon”, and on the other it’s lambasting a young woman’s vanity, before inviting people to: “Take a day and walk around/Watch the Nazis run your town.” The preposterous cod-operatic ‘Duke Of Prunes’ follows, except that beneath those vocals and frankly absurd lyrics, there’s a rather gorgeous tune; one that would get hauled out multiple times for instrumental (and even orchestral) renderings over the years. In this piece, there’s also the seed of what can only be described as the prototype prog-rock of the 1969 version of The Mothers, with multiple time changes and a mad freeform section.

‘Call Any Vegetable’ is styled after a call-and-response gospel number, except that it’s advertising relationships with green edible matter, and even suggesting that once the union is forged, the brethren may wish to attend the church of their choice to worship together. Not only is it suggesting erotic adventures with vegetables, but it’s bafflingly sacrilegious to boot.

The next piece allows some reflection on the lyrical insanity of the previous few songs. It’s a long modal instrumental workout called ‘Invocation And Ritual Dance Of The Young Pumpkin’ that’s essentially an excuse for Zappa to play his guitar. And does he ever. Except that the young guitar-slinger isn’t confident enough to boost the volume levels, and hasn’t yet discovered all the gadgets he later got into to get the kind of sounds he really liked from that damn geetar; it’s a good solo, but tonally it’s thin and twangy, and it’s almost submerged under parping saxes and percussion. After which there’s a brief ‘Soft Sell Conclusion’ – a coda, if you will, to the first suite – before the killer second half.

But just like the previous version of Absolutely Free on CD, an unrelated single that was released around the same time, together with its b-side, is thrown into the mix. This is unfortunate, because it disturbs the flow of the original album, and neither ‘Big Legged Emma’, nor ‘Why Don’tcha Do Me Right?’ are of the same vein as the album. The first is entertaining enough, but fairly silly and undemanding (“There’s a big dilemma/’Bout my Big Leg Emma… She was my steady date/Until she put on weight”, etc), while the second is a gritty blues that fails on account of the repetitive harpsichord mixed so much louder than the guitar. These are footnotes and would have been better at the end of the programme, or on a separate odds and sods collection. I recommend programming them out for the sake of Zappa’s much-vaunted ‘conceptual continuity’.

From here on in, it’s all just super. ‘America Drinks’ is a short piece of cocktail madness to introduce the second suite, and includes some ecstatic snatches of instrumental lunacy. What follows next are three of Zappa’s most perfect pop songs, each of them short, perceptive social/political observations that set the stage for the album’s magnum opus, ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’. But we’ll get to that soon. ‘Status Back Baby’ addresses the issue of peer group pressure at high school, and what happens when “pom pom” girls look down their noses at you despite craven attempts to fit in. ‘Uncle Bernie’s Farm’ is an incise condemnation of industrial toy makers that quickly enlarges its pointed commentary to wider political concerns: “There’s a man who runs the country/There’s a man who tried to think/And they’re all made out of plastic/(When they melt, they start to stink)/There’s a book with smiling children/Nearly dead with Christmas joys/And smiling in his office/Is the creep who makes ‘the toys’.” The dedicated listener will remember a character from Freak Out! called Suzy Creamcheese, who’s back on ‘Son Of Suzy Creamcheese’, a perky little number describing her descent from cheerleader to hippy drop-out.

And then there’s ‘Brown Shoes Don’t Make It’, seven-and-a-half minutes that stands as one of Zappa’s greatest pieces, a tour de force in innumerable ways. As a composition, it squeezes in a riot of styles and methodologies, including blues and burlesque, modern classical and an audacious use of musique concrete, a type of collage/editing process invented in the 1940s but until Zappa, confined pretty much to the avant-garde and the academy. This involved editing tapes by hand, and then applying pre-digital trickery to speed parts up, and slow parts down. As a piece of music, it’s incredible. As a social critique of America circa 1966, it hits the bulls-eye. Once again, Zappa combines high school and congress by combining several narratives. There’s the schoolboy: “Brown shoes don’t make it/Quit school, why fake it?/… Be a plumber he’s a bummer/He’s a bummer every summer/Be a loyal plastic robot/For a world that doesn’t care.” And there’s the husband and/or congressman, who could be the grown up version of the same boy: “Be a jerk and go to work/Do your job, and do it right/Life’s a ball (TV tonight!)… Do you love it, do you hate it?/There it is, the way you made it/A world of secret hungers/Perverting the men who make your laws/Every desire is hidden away.”

This is a theme Zappa would come back to again and again through his career: the way we’re conditioned to do all the mundane stuff society expects to keep us behaving like loyal robots, and the perverted effect the compromise has on our natural instincts and passions. The lyrics get so racy that, after awhile, things get a bit uncomfortable for the listener. The scenario? The husband/congressman is fantasising about doing unspeakable things to his 13-year-old daughter, who repeatedly asks: “What would you do, Daddy?” To which he replies: “I’d… smother my daughter in chocolate syrup/And strap her on again!/She’s my teenage baby, and she turns me on/I’d like to make her do a nasty/On the White House lawn.” And so forth! One can only imagine the outrage this would have caused the moral guardians of America before any naughty words had even been uttered on record or television. It’s a savage piece that got right to the heart of one of modern, suburban society’s materialist concerns, and had the guts to talk about something that was really much more worthy and real than ‘All You Need Is Love’.

Finally, the album signs off with a short reprise of ‘America Drinks’, called ‘America Drinks & Goes Home’, which is set late at night in some seedy bar when everything’s out of control and the drunk MC isn’t making any sense and the crowd are screaming and you can hear glass scrunch on the floor… all in glorious stereo.

Absolutely Free is one of the defining moments of the late ‘60s and a record that, like The Doors’ best work, really keys in to the character of Los Angeles. It’s brash and hard to take, and putting it on the hi-fi is a commitment to sit and listen intently – like most Zappa, this is not background music. What more can I say? It’s worth the effort.

Sound quality and presentation: For this new Universal label version of the album, the artwork has been turned around but has retained its integrity, and includes a foreword liner note that isn’t included on the Ryko version. Like the original album, it contains (most of) the lyrics but not the libretto, but that can be found online, no doubt. This was always one of Zappa’s more problematic albums, sonically. Presumably because it was recorded speedily, the sound is rather thin. The new version, from the original master, is effortlessly better-sounding than the Ryko version. The most prominent difference is the bass, which is suddenly big and rather boomy, and the recording suddenly sounds fatter, as though it’s got some air around it. We’re informed that analogue transfers were made by Joe Travers in March this year. Other tech info: DSD Signal path: Ampex ATR-102/Meitner Mark II A/D Converter via Sonoma Digital Workstation, Super Audio Center. And it’s mastered by Doug Sax at the Mastering Lab. GARY STEEL

Sound = 3.5/5

Music = 5/5