To mark legendary expat pianist Mike Nock’s newly announced 2024 induction into the NZ Music Hall of Fame, GARY STEEL digs into his archive for an interview from way back in 1983. And keep reading for all the info on Nock’s NZ Music Hall of Fame accolade.

“I enjoy a lot of the new wave music, punk, rock and roll. It’s not my style, but some of it I really do enjoy because it has that quality that I look for in all music. A lot of it doesn’t, but that’s the same in any style of music.”

“I enjoy a lot of the new wave music, punk, rock and roll. It’s not my style, but some of it I really do enjoy because it has that quality that I look for in all music. A lot of it doesn’t, but that’s the same in any style of music.”

Here’s a man with an open mind. Internationally acclaimed expatriate jazz pianist Mike Nock’s only criterion is whether the music is good or bad. In a sense he’s calling ‘good’ music that which is played well. But ‘played well’ means something different than Mr Average Kiwi’s perception allows for.

“Some musicians can study all their lives, classically or otherwise, and still play bad music,” says Nock. “They’ll play all the right notes, but musically it’s bad. Somebody else has never had a music lesson in his life, doesn’t know the first thing about what he’s doing; he can pick up something and make good music out of it.

“Some musics you’ve got to be able to understand more than others – you’ll get more out of it if you understand it – but understanding is not prerequisite to enjoying music. If it is, there’s something wrong, because music is something that you listen to.

“Music merely as an intellectual exercise is meaningless.”

Nock has the perfect combination of experiences on which to base his claims. Growing up in New Zealand, the young musician played with rock and roll bands in the 1950s before cementing his love affair with jazz, finally to end up in the music’s Capital City, New York, in 1958.

The self-taught musician built up a steady reputation and played with some of the jazz greats. His interest in a variety of musical forms led him to session work with people as diverse as Yusef Lateef and Dionne Warwick. In the early 1970s, Nock was a pioneer in the jazz-rock fusion genre popularised by people like Chick Corea’s Return To Forever and Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters.

Having left school at an early age, he applies himself rigorously to the study of his chosen art (he calls himself a music student). It is not surprising to learn that Nock is from the Teach Yourself school of thought.

“Just because you’ve gone to an academy and got your letters does not mean to say you’re a good musician. New Zealanders think that way – they tend to look up to somebody who’s had more education as smarter. You may have educated yourself much better, even if you don’t know the square root of something or other.”

Qualifying this, Nock says: “Having study and knowledge is an incredible asset, as long as you don’t become self-conscious about it… which is true of musical snobs.

Qualifying this, Nock says: “Having study and knowledge is an incredible asset, as long as you don’t become self-conscious about it… which is true of musical snobs.

“To me, not a high percentage of classical musicians end up playing musically well, because they’ve become too self-conscious. Technique is just a means to an end. Knowledge is just a means for getting to that point.”

And: “Poor teaching has probably done more to fuck up more musicians than lack of teaching ever has.”

Taking a stroll back to the 1970s, Nock gives up fusion. He doesn’t begrudge the success of Hancock and Co:

“Herbie really loves what he’s doing. The rewards for those guys have been quite tremendous, but they’ve probably worked much harder at doing that than they did with their jazz thing.”

As for himself: “I was always a little bit reluctant to get involved in that situation – if it had happened I would have welcomed it! – but I’ve always preferred to play on a more personal level. It got to the point where we were starting to become quite successful, and I had really mixed feelings about it. It’s like you’ve created a monster.”

So Nock saw himself, while remaining incredibly eclectic, getting back into acoustic piano and releasing a series of acclaimed albums. One of the latest was on the prestigious German label ECM, Keith Jarrett’s label. “I enjoyed immensely doing it. That record was a combination of me and Manfred Eicher, the producer (and ECM guru). It was what he wanted. It was what I wanted also. He liked the rather sombre mood… I would never have the nerve to put such an unrelieved sombreness on a record.”

Between his various projects, Nock has fitted in approximately one visit to his home country per year for the last 10 years. He’s proud of the standard of music being made here.

Television brought Nock back to NZ this time. Currently screening is a seven-part series (Nock On Jazz) in which the man talks with and introduces many, mainly local, musicians of his personal choice.

His aim in presenting the series is to get across to an audience that has mislabeled jazz in all its facets, in ignorance.

“Many, many people in this country, young and old… you mention the word ‘jazz’ and they immediately say they don’t want to know about it. That really blows my mind! Because jazz is just a term that’s applied to such a wide variety of musics. It’s applied to almost any music that’s improvised, to some extent. You find elements of jazz in all kinds of music. But people have this idea that jazz means something, and it’s something a lot of people dislike.

“What I’ve tried to do on this programme is just to show some of the variety of music that’s available in New Zealand.

“Some of these people (the musicians) are very interesting, because they’ve made a commitment to do something that is not necessarily economically oriented. Doing something that they love to do. And a lot of these people have devoted their lives to it.

“Saying you don’t like jazz is really as silly as saying you don’t like people, or don’t like music.”

Local music has been prone to “a certain national inferiority complex that’s changing as New Zealanders become more aware that they do have a lot to be proud of. New Zealand is, more and more, getting its own indigenous culture, its own indigenous attitude.”

For Nock himself, he says he has “always been motivated by musical curiosity – I’ve specialized in the field of jazz, but jazz brings such a broad field.

“You tend to get into little niches,” he says. “And then you get out of them. It’s just a natural progression, nothing forced. You’ll find yourself going up a path. No one likes this path. So you’re in it anyway, exploring it for what it’s worth. Until something else comes along.”

He says that in his own music he is moving away from the introspective style typified by the ECM recording. “I’m coming back to a way of playing that I used to play 20 or 30 years ago. Of course it has a much more sophisticated approach to it. But I can see a circle.”

He says that in his own music he is moving away from the introspective style typified by the ECM recording. “I’m coming back to a way of playing that I used to play 20 or 30 years ago. Of course it has a much more sophisticated approach to it. But I can see a circle.”

His current love is music for films. “One of the reasons I really like the idea of film music, apart from the obvious one of mixing up sound and music and drama, is the idea of… the really good film music person should be able to relate to a very wide variety of music to be able to use the appropriate musical style to what’s going on. And to me that’s really interesting. Country music even! Be open to it.”

And what of the poor hapless fan who can’t make head nor tail of a career with such a diverse approach?

“It’s been a problem for those who want to identify,” admits Nock. “It’s cut down my audience appeal, because people haven’t been able to say ‘Oh, that’s a Mike Nock sound.’ Although I think I have a personal approach.”

Living in America is financially “rough”, says Nock. What’s on the schedule when you get back? “I don’t know what’s happening. I’ll get on the phone!”

In the meantime, if you search hard enough, you may be able to find recorded evidence of Nock’s existence, but not much of it. As the man says: “Record companies are full of shit. Especially in this country. These people will tell me one thing, and they’re just lying. They got no reason to lie to me! Apparently Keith Jarrett’s last solo record in New Zealand sold 25 copies. In the States it’s been acclaimed as the best album he’s ever done. There’s something wrong there.”

Balding Nock may be. Old he ain’t. A true all-rounder with an astoundingly open minded attitude, he struck this journalist as a case of positive energy the local scene can’t afford to do without. At least once a year.

“The rules are just what you want to do. The best musicians are the ones who know the rules, then disregard them.” GARY STEEL

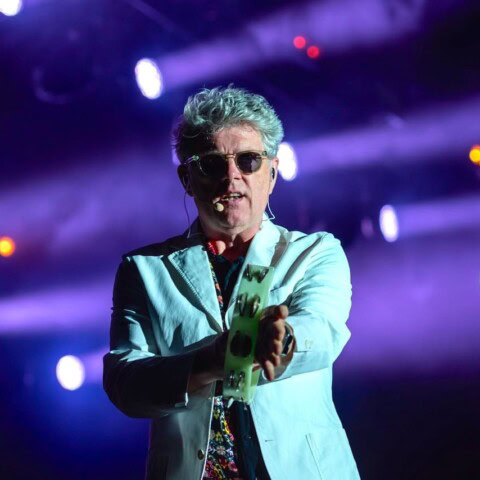

+ Originally published in TOM, May 1983. Photos by Gary Steel.

Here’s the APRA AMCOS press release in full:

Mike Nock to be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame

APRA AMCOS Aotearoa are thrilled to announce jazz performer and composer Mike Nock (ONZM) will be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the 2024 APRA Silver Scroll Awards on Tuesday 8 October at St James Theatre, Wellington.

APRA AMCOS Aotearoa are thrilled to announce jazz performer and composer Mike Nock (ONZM) will be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the 2024 APRA Silver Scroll Awards on Tuesday 8 October at St James Theatre, Wellington.

From stowing away on a boat to Sydney, to winning a scholarship from DownBeat magazine to attend Berklee College of Music, to establishing himself in the American heartlands of jazz, Mike Nock’s story has always been one of fierce ambition, determination, and remarkable talent.

From Christchurch to Boston, from San Francisco to New York City, Nock’s seven-decade career has seen him play with an enormous breadth of musical luminaries including Yusef Lateef, Art Blakey, Johnny O’Keefe, Dionne Warwick, and Michael Brecker, before returning to Sydney in the 1980s, to teach at the Sydney Conservatorium. He then spent 30 years sharing his knowledge with the next generation of Australasian jazz composers and players, while balancing a prolific career of composing, recording, and touring (he has more than 40 albums to his name, and over 100 on which he has featured as a player).

Since he began taking piano lessons with his father at the age of 11, Nock’s affinity with the keys has been evident. Determined to continue his musical development after his father passed suddenly, Nock continued his lessons with Ngaruawahia pharmacist Bert McNamara. Later, there were moves to Nelson and Wellington where he found other like-minded musicians to play with, including The Fabulous Flamingos, a Palmerston North-based dance outfit promoted by popular entertainer Johnny Cooper.

Auckland was the next stop, in 1957, where Nock developed formative relationships working with rock ‘n’ roll singer Johnny Devlin, drummer Tony Hopkins, trumpeter Kim Paterson and drummer Lachie Jamieson (who had spent time in the US playing with Sonny Rollins). Nock ultimately wanted to get to the US himself and figured the best way might be via Sydney – leading to his stint as a stowaway.

He was 18, hungry for gigs, and quickly embedded himself in the local scene, forming The 3-Out Trio with bassist Freddie Logan and drummer Chris Karan, who became one of the most popular jazz groups in late ‘50s Sydney. They played relentlessly, and their 1960 EMI Columbia release, Move, sold like hotcakes.

When Nock found out he had a scholarship to Berklee, The 3-Out Trio planned a tour to England, playing for their passage, and spent a few months performing in Europe before Nock moved to Boston to study.

With little money or support, Nock was forced to hustle for gigs while studying and quickly established himself in the local jazz scene. His undeniable talent soon found him picking up gigs with local luminaries, later becoming an integral member of Yusef Lateef’s band in the early ‘60s. Lateef’s band leadership, as well as their timeless post-bop improvisational jazz, was not only a profound influence on Nock, but also afforded them a not-insignificant profile in the US scene. This later provided the opportunity for Nock to form and lead his own groups once more.

With little money or support, Nock was forced to hustle for gigs while studying and quickly established himself in the local jazz scene. His undeniable talent soon found him picking up gigs with local luminaries, later becoming an integral member of Yusef Lateef’s band in the early ‘60s. Lateef’s band leadership, as well as their timeless post-bop improvisational jazz, was not only a profound influence on Nock, but also afforded them a not-insignificant profile in the US scene. This later provided the opportunity for Nock to form and lead his own groups once more.

Nock relocated to the West Coast and in 1967 formed The Fourth Way, an American jazz quartet that played primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area through the early ‘70s, releasing three albums to critical acclaim – predominantly composed by Nock – for the rock division of Capitol Records. The group’s first LP, from 1969, grew to be considered a sampler’s secret paradise – with pilfered breakbeats and flourishes from the release later appearing in the ‘90s and ‘00s work of many era-defining DJs, such as Diplo.

The Fourth Way are celebrated as early pioneers of fusion jazz groups, mixing jazz with rock music while playing amplified instruments. Group high points include playing the prestigious 1970 Montreux Jazz Festival as well as performing as the opening act for Miles Davis’ group. The Fourth Way was on fire that night and Davis found himself upstaged by the young San Francisco group, with Davis reportedly lamenting, “Man, I’m never going on second again.”

Nock moved to New York in the mid-1970s where he stayed for the next ten years, releasing Magic Mansions (with Charlie Mariano), In, Out and Around (with Michael Brecker), Climbing (with John Abercrombie and Tom Harrell), Succubus with Alex Foster as well as two solo albums: Piano Solos and Mike Nock Solo (recorded in Australia). A standout release from this period is his trio record, Ondas, released on storied jazz label ECM.

His return to the Antipodes in the mid-80s did nothing to slow down his creative output, with a successful Sydney teaching career accompanying multiple releases with The New York Jazz Collective, as well as albums with young Australian and Aotearoa musicians.

The sheer scope of writing for his trio, big band, and chamber groups is substantial, as well as solo piano pieces recorded by Australian virtuosi Michael Kieran Harvey and Simon Tedeschi, as well as New Zealander Michael Houstoun. During this period, Nock somehow found the time to record a series for TVNZ, Nock On Jazz, platforming the genre and its luminaries to a domestic television audience. He also did a stint as music director of Naxos Jazz from 1996 to 2002, overseeing the production of more than sixty internationally released albums.

Nock has already received a variety of appropriate accolades – Best Jazz Album at the NZ Music Awards in 1987, appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to jazz in 2003, inducted into the Australian Jazz Hall of Fame in 2009, presented with the Don Banks Music Award in Australia in 2014 – but his impact on the landscape of music, and in particular jazz in Aotearoa is undeniable, and we’re thrilled to have this opportunity to celebrate Nock’s enduring influence and incredible body of work.

Anthony Healey, Head of APRA AMCOS Aotearoa, says: “Mike’s achievements, which very much continue today, are that of a much-celebrated performer, collaborator, musician, pianist, composer and educator. His talents are many and varied and the unifying strand that runs through them all is the single-minded dedication he has made to his craft.

Mike has been an inspiration. He has shown people that creativity, and in particular music, is a universal language. He’s taken that message from here to around the world, leading the way for New Zealand artists everywhere, encouraging and empowering them to do the same.

To his fellow musicians here in Aotearoa, Mike shows enduring generosity and support. He leads by example as an artist, with a call to arms that is enduringly passionate. We can’t think of a better person to celebrate and honour as an example of what has made our musical landscape what it is, and an example of what we can all aspire to.”

At 84, Nock is still going strong. His most recent album, Hearing, released in 2023, is a testament to his continued contemporary jazz prowess, while also finding time to contribute to a future documentary, and, as ever, looking forward to a slew of upcoming live performances in the calendar.