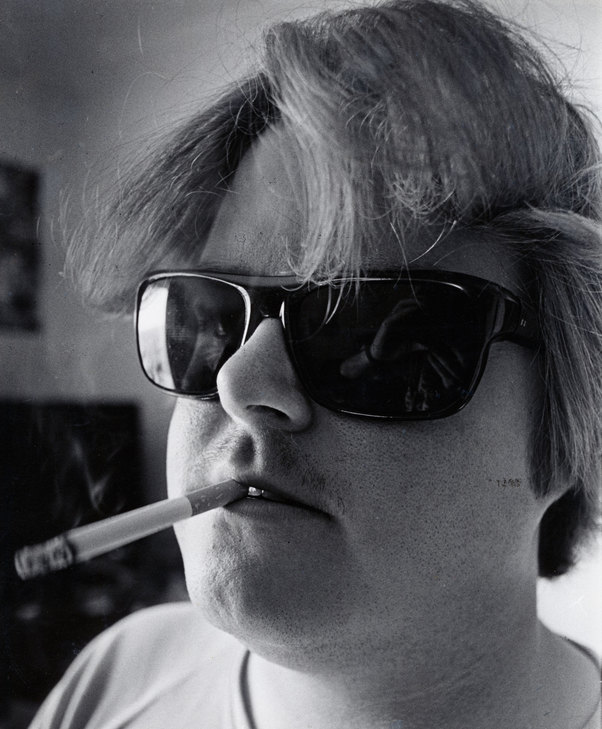

Ron Kane was an American who loved NZ music at a time we barely acknowledged it, a record collector supreme, and part of a very strange musical group called The Decayes. GARY STEEL pays tribute to a good friend who died earlier today.

I woke up this morning to several messages from friends telling me that Ron Kane had died. In the blur of grief, I wrote on his timeline: “Ron was etched into the fabric of my world. Devastated.”

About one second later, it occurred to me that had he read that, Ron would have poured scorn on my sentiment. I can imagine “…etched into the fabric of my world” becoming a standing joke during a long day of driving around LA, thumbing our way through thousands of records, eating – always eating – and long-form conversation.

Ron couldn’t stand bullshit, and would mercilessly mock pretension. It was one of the many things I loved about him.

I wrote about Ron’s contribution to New Zealand’s music culture in my AudioCulture story, but not our friendship, which lasted more than 35 years without a blip. Kane established contact in 1981 by writing to the Wellington-based music magazine I was editing at the time, and he flew to New Zealand a few months later. He fit my naïve preconceptions of a larger-than-life, loud American music industry person, and I was completely overwhelmed by the sheer force of his personality.

Back then, there was a certain antipathy towards New Zealand music, and English and American bands were viewed as superior. I loved NZ music, but Ron shamed me in his enthusiasm and record-collecting fervour. Back then, record shop bins were groaning with unwanted NZ records, and Ron bought them all, eventually amassing what must be the definitive collection of New Zealand music (at least up to about 1995) at his Long Beach home.

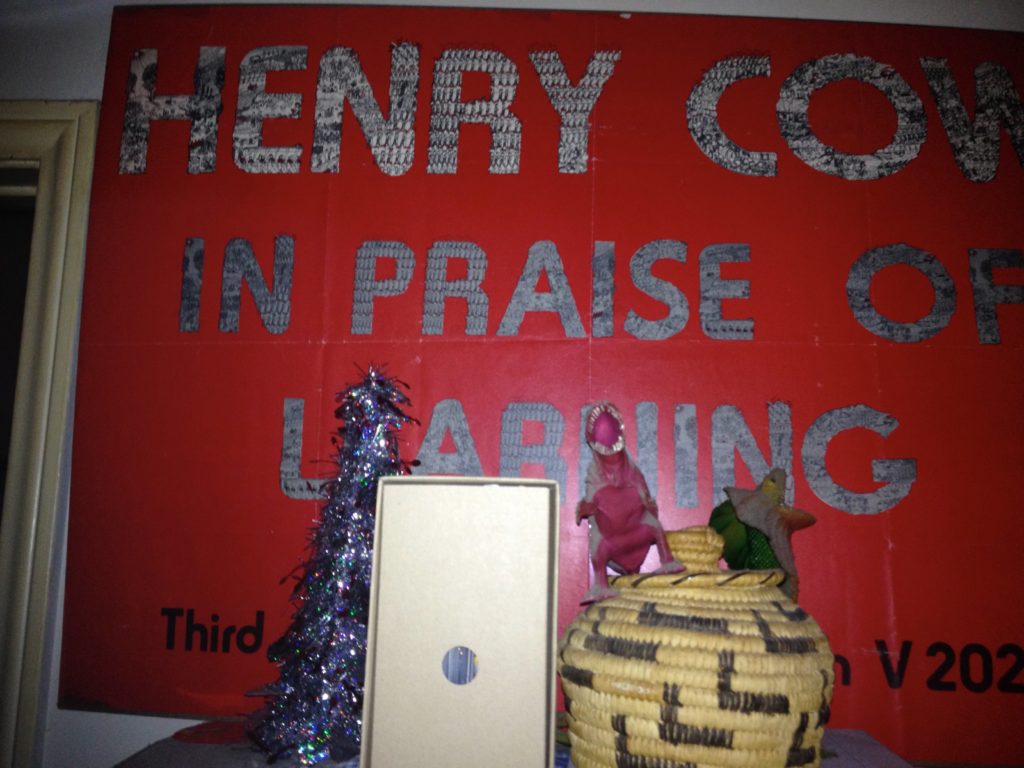

We became fast friends, however, over our shared passion for Frank Zappa, and the various lesser-known strains of progressive rock that had emanated out of the UK and Europe through the 1970s, with a special affection for Henry Cow, Hatfield & The North, Faust and Can. Ron’s music knowledge was vast, and the guy could even remember specific serial numbers of albums and singles.

I’d been a Zappa fan from the age of 14, but had grown up in Hamilton and had never met anyone else who liked Zappa. It was a lonely, if rewarding, pursuit. Ron not only had the largest Zappa collection of anyone I’ve ever met (for instance, he had sought out dozens of copies of the classic We’re Only In It For The Money, as issued by different countries around the world), but he had grown up in Los Angeles, and through his older brother, had become a Zappa fan in the late ‘60s. This meant that he had a contextual understanding of Frank Zappa and his recordings that was revolutionary to me.

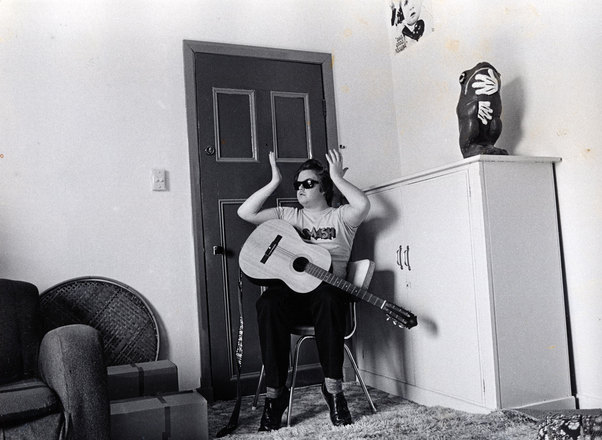

In short, I shared with Ron a similar musical aesthetic: punk attitude with progressive musical leanings. This aesthetic came through loud and clear on the DIY, private-press albums he recorded with his group The Decayes, which were determinedly anti-trend, and proudly the work of suburban Americans who were influenced by obscure European avant-rock groups like Lard Free.

What I really dug about Ron was that he refused to accept the lie that all the best music comes from the US and the UK, or the lie that the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan are some kind of holy trinity, under which sit the Springsteens of the music world. Ron and myself moved around in a musical parallel universe where lesser known artists weren’t inferior to “the greats”.

So, I’d met Ron expecting him to be an American music industry type, surprised that he was ardent about NZ music at a time when it was largely unloved, only to be surprised again to discover that I’d found a friend whose tastes in music were aligned with my own. And then I was surprised all over again to discover that he had a band of his own, and that despite his own proud statement that The Decayes were the worst band in the world and couldn’t play their instruments, I really liked them (and still do).

[I have to add here that over the years I’ve met many really lovely musicians who I liked a lot, only to have our friendship sullied by the fact that I thought their music really sucked. It’s a joy, therefore, to discover that a person you like a lot actually makes really great music, too. It has happened several times since].

Over the next decade, Ron visited NZ on many occasions, and those visits were always memorable. He was big at soaking up the elements of local culture that appealed to him, together with those that stuck out as being particularly stupid, so one of the first things we did was have a night on the tiles drinking as much Lion Brown as possible, followed by crappy Courtney Place midnight takeaways and the inevitable vomiting in the street. [Hey, we were both young men back then]. He was particularly amused by the Super Liquor Man retail grog shops for having the temerity to link booze and a genuine (if made-up) American icon.

Ron took in as many gigs as possible, and was lucky to see a couple of performances by The Gordons at The Last Resort in ’81, and to capture them on his trusty Sony Professional Walkman. We relied on public transport to get out to the Quinn’s Post Tavern in Upper Hutt to see DD Smash at their beer-swilling peak play to a rowdy crowd. I’m still not sure how we got home to central Wellington. Now here’s the thing: I would never have ventured out to the hinterlands like that of my own volition. For me, the music scene was all about central Wellington, but Ron didn’t get the divide between the post-punk aesthetic and the populist rock’n’soul of Dave Dobbyn and his cohorts: he just knew they both rocked.

In 1983 Ron brought his then-girlfriend, Gwynne Garfinkle, down to NZ and I ended up driving them around the lower half of the North Island to attend a gig in Gisborne in which the likes of Tall Dwarfs, Cake Kitchen and many other NZ alt-rock groups were performing. It was in an acoustically horrible aircraft-hanger-like building, and there was an air of violence in the crowd, so we ended up retreating to a burger joint across the road, where a tussle was going on between two sets of Pacific Island men, one of whom was calling the other a “black bastard.” Ron found this most curious, although I think his biggest surprise was the seeming integration between Maori and Pakeha in NZ. He lived in Long Beach, only blocks away from the infamous Compton. There, you had white enclaves, with a buffer zone housing mostly Hispanics, and then black-only areas.

Throughout the ‘80s my friendship with Ron was a constant, and there was also an element of reciprocal pragmatism: I sent him vast amounts of New Zealand music, and he would send me Zappa-related items, along with numerous compilation C90 cassette tapes and VHS recordings from American television. I’ve still got them all, including the videos containing just about every interview Charles Manson ever gave, the most ridiculous television hellfire preachers, and lots of obscure clips of obscure bands.

Then there was Holland, Australia and Japan. Ron quickly became disenchanted with the UK music scene as post-punk diluted into New Romantic swill. A fan of the kind of idiosyncratic pop typified by Phil Judd’s The Swingers but also a long-time admirer of electronic music, he found much to his liking in Dutch bands like The Nits. Japan would become his major musical fascination for the rest of his life, as his interest in NZ music quickly dissipated after the late ‘80s.

I have Ron to thank for that, too, as he introduced me to groups like YMO (Yellow Magic Orchestra), the solo work of its members Ryuichi Sakamoto, Haruomi Hosono and Yukihiro Takahashi, and an ever-widening network of Japanese music that neither fit Julian Cope’s definition of “cool, alt” Japanese rock but also wasn’t in bed with the “Idol” culture of “J-Pop”, either. Here were musicians that were comfortable making everything from outright avant-garde music through to commercial pop without the usual aesthetic barriers, and Ron was a champion of the so-called Shibuya-kei scene of the ‘90s (Pizzicato 5, Flipper’s Guitar) where everything was permissible: sampling easy listening music, incorporating Brazilian influences, hip-hop, girl-group pop.

It was 1988 before I finally made it to America, and got to hang out with Ron on his home territory. I still have the video he made of my experience there. “In LA, you are your car”, Ron said, and indeed, it felt like we spent most of our time driving from one destination to another, which at least gave us long form conversational opportunities. I now wish I had recorded some of the conversations from that and the many subsequent visits over the years, because it was invariably in those conversations that Ron could tell his complex stories. He was an allusive character, and would generally only tell personal stories through the music he loved.

It was only when he was a bit tipsy that the “personal” Ron would emerge, and that’s when I heard all about his family, the difficult relationship with his Dad, and the tragedies around his much-loved brother, and one of his sisters, as well as Ron’s own unhappiness at his marriage breakdown in the ‘90s and subsequent loneliness. Ron ended up taking on an administrative job that he never enjoyed, but he endured it for its retirement benefits. That retirement came in 2014, and he subsequently got to travel to Japan for the umpteenth time, attend many record swap-meets, and start to organise and digitise his vast music collection.

Ron was so knowledgeable and so passionate about music that he could have ingratiated himself with the music industry, but his fandom ran too deep for that, and his strong opinions would have run foul of industry protocols. I know that for some time in the ‘90s he was consulted by Warners, because he was so good at identifying samples buried away in rap records. But he was the type of person who could never have put his heart into something he didn’t love. Having started out as a record store guy, he ended up working for an import company called Liquorice Pizza, where he could get hold of all those elusive Japanese discs.

As Murray Cammick said in a Facebook post: “In the 80s he was the world’s greatest NZ music fan, by far.” On the surface, Ron was simply an ardent collector or records (and music and film ephemera), but the reality is far more complex.

He was generous, too. When the idea of the AudioCulture music archive was first mooted and a physical version (ala the Film Archive) seemed a possibility, Ron offered to gift his entire NZ music collection to it. That offer wasn’t taken up, because AudioCulture became a web-only repository for writing about NZ music instead.

In one of the last emails I got from Ron, he wrote: “These days I am alone a lot (sad face), so I have been trying to think of how to occupy my time. I do still go to record stores, though I haven’t yet hit 35,000 titles.” His plan was to stop at 35,000 and have to sell an equal amount to any new titles acquired.

We had been talking about meeting up in Japan. It guts me that that will now not happen.

Ron Kane was 59.

PS, Late last year I asked Ron for a list of his 5 favourite Japanese albums. Here it is:

Top 5?

Hajime Tachibana – “H”

Cornelius – “Fantasma”

Haruomi Hosono – “S-F-X”

Watermelon (Toshio Nakanishi) – “Cool Music”

Mute Beat (Kazufumi Kodama) – “Still Echo” (aka “No. 0”)

A further 5:

Ryuichi Sakamoto – “Illustrated Music Encyclopedia”

Yukihiro Takahashi – “What? Me Worry”

Y.M.O. – “Technodelic”

Pizzicato Five (Yasuharu Konishi) – “Bossa Nova 2001”

P-Model (Susumu Hirasawa) – “In A Model Room”

…probably.

– Ron

Thank you for sharing such a wonderful tribute to your friend.

What an incredibly interesting and complex man. Thank you for telling his story.

I met Ron Kane in Bergen-Op-Zoom in Holland on January 18th 1992 during a gig of my favorite band MAM. He taped the whole concert and sent it to me. We met again a year later in Amsterdam where we talked about his great passion, music. What a great man. #RIP

I have just inherited a lovely copy of The Fourmyula, adorned by standard issue Property of Ronald Kane stickers …